Why You Fear Speaking And What To Do About It

(This is a full chapter from the bestseller Confessions of A Public Speaker, Chp 2. The Attack of The Butterflies)

“The best speakers know enough to be scared…the only difference between the pros and the novices is that the pros have trained the butterflies to fly in formation.”

Edward R. Murrow

While there are good reasons people fear public speaking, until I see someone flee from the lectern mid-presentation, running for his life through the fire exit on stage left, we can’t say public speaking is scarier than death. This oddly popular factoid, commonly stated as “Did you know people would rather die than speak in public?” is a classic case of why you should ask people how they know what they think they know. This “fact” implies people will, if given the chance, choose to jump off buildings or swallow cyanide capsules rather than give a short presentation to their co-workers. Since this doesn’t happen in the real world—no suicide note has ever mentioned an upcoming presentation as the reason —it’s worth asking: where does this factoid come from?

The source is The Book of Lists by David Wallechinksy et al. (William Morrow), a trivia book first published in 1977. It included a list of things people were afraid of, and public speaking came in at number one. Here’s the list, titled “The Worst Human Fears”:

- Speaking before a group

- Heights

- Insects and bugs

- Financial problems

- Deep Water

- Sickness

- Death

- Flying

- Loneliness

- Dogs

- Driving/Riding in a car

- Darkness

- Elevators

- Escalators

People who mention this factoid haven’t seen the list because if they had seen it, they’d know it’s too silly and strange to be taken seriously. The Book of Lists says a team of market researchers asked 3,000 Americans the simple question, “What are you most afraid of?”, but they allowed them to write down as many answers as they wanted. Since there was no list to pick from, the survey data is far from scientific. Worse, no information is provided about who these people were.[1] We have no way of knowing whether these people were representative of the rest of us. I know I avoid most surveys I’m asked to fill out, as do many of you, which begs the question why we place so much faith in survey-based research.

When you do look at the list, it’s easy to see that people fear heights (#2), deep water (#5), sickness (#6), and flying (#8) because of the likelihood of dying from those things. Add them up, and death easily comes in first place, restoring the Grim Reaper’s fearsome reputation. Facts about public speaking are often misleading since they frequently come from people selling services, such as books, that benefit from making public speaking seem as scary as possible.[2] Even if the research were done properly, people will tend to list fears of minor things they encounter in everyday life more often than more fearsome but abstract experiences like dying.

When thinking about fun things like death, bad surveys, and public speaking, the best place to start is with the realization that no has died from giving a bad presentation. Well, at least one person did, President William Henry Harrison, but he developed pneumonia after giving the longest inaugural address in U.S. history. The easy lesson from his story: keep it short or you might die. This exception aside, by the time you’re important enough, like Gandhi or Lincoln, for someone to want to kill you, it’s not the public speaking that’s going to do you in. Malcolm X was shot at the beginning of a speech in 1965, but he was a fantastic speaker (if anything, he was killed because he spoke too well). Lincoln was assassinated watching other people on stage. He was shot from behind his seat, which points out one major advantage of giving a lecture: it’s unlikely someone will sneak up from behind you to do you in without the audience noticing. Being on stage behind a lectern gave safety to President George W. Bush in his last public appearance in Iraq when, in disgust, an Iraqi reporter threw one, then a second shoe at him. Watching the onslaught from the stage, Bush had the advantage and nimbly dodged them both.

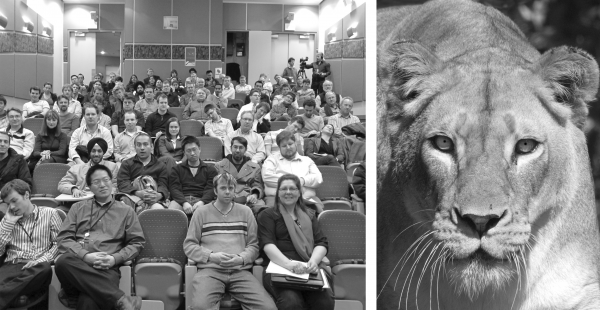

The real danger is always in the crowds. Fans of rock bands like The Who, Pearl Jam, and the Rolling Stones have been killed in the stands. And although the drummer for Spinal Tap did mysteriously explode while performing, very few real on-stage deaths have ever been reported in the history of the world. The danger of crowds is why some people prefer the aisle seats—they can quickly escape, whether they’re fleeing from fire or boredom. If you’re on stage, not only do you have better access to the fire exits, but should you faint, fall down, or suffer a heart attack, everyone in attendance will know immediately and call an ambulance for you. The next time you’re at the front of the room to give a presentation, you should know that, by all logic, you are the safest person there. The problem is that our brains are wired to believe the opposite; see Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1. When you see the left, your brain sees the right.

Our brains, for all their wonders, identify the following four things as being very bad for survival:

- Standing alone

- In open territory with no place to hide

- Without a weapon

- In front of a large crowd of creatures staring at you

In the long history of all living things, any situation where all the above were true was very bad for you. It meant the odds were high that you would soon be attacked and eaten alive. Many predators hunt in packs, and their easiest prey are those who stand alone, without a weapon, out on a flat area of land where there is little cover (e.g., a stage). Our ancestors, the ones who survived, developed a fear response to these situations. This means despite my 15 years of teaching classes, running workshops, and giving lectures, no matter how comfortable I appear to the audience when at the front of the room, it’s a scientific fact my brain and body will experience some kind of fear before, and often while, I’m speaking.

The design of the brain’s wiring—given it’s long operational history, hundreds of thousands of years older than the history of public speaking, or speaking at all for that matter—makes it impossible to stop fearing what it knows is the worst tactical situation for a person to be in. There is no way to turn it off, at least not completely. This wiring is so primal that it lives in the oldest part of our brains where, like many of the brain’s other important functions, we have almost no control.

Take, for example, the simple act of breathing. Right now, try to hold your breath. The average person can go for a minute or so, but as the pain intensifies—pain generated by your nervous system to stop you from doing stupid things like killing yourself—your body will eventually force you to give in. Your brain desperately wants you to live and will do many things without asking permission to help you survive. Even if you’re particularly stubborn, and you make yourself pass out from lack of oxygen, guess what happens? You live anyway. Your ever faithful amygdala, one of the oldest parts of your brain, takes over, continuing to regulate your breathing, heart rate, and a thousand other things you never think about until you come to your senses (literally and figuratively).

For years I was in denial about my public speaking fears. When people asked, after seeing me speak, whether I get nervous, I always did the stupid machismo thing. I’d smirk, as if to say, “Who me? Only mere mortals get nervous.” At some level, I’d always known my answer was bullshit, but I didn’t know the science, nor had I studied what others had to say. It turns out there are consistent reports from famous public figures confirming that, despite their talents and success, their brains have the same wiring as ours:

- Mark Twain, who made most of his income from speaking, not writing, said, “There are two types of speakers: those that are nervous and those that are liars.”

- Elvis Presley said, “I’ve never gotten over what they call stage fright. I go through it every show.”

- Thomas Jefferson was so afraid of public speaking he had someone else read the State of the Union address (George Washington didn’t like speaking either)[3].

- Bono, of U2, claims to get nervous the morning of every one of the thousands of shows he’s performed.

- Winston Churchill, JFK, Margaret Thatcher, Barbara Walters, Johnny Carson, Barbara Streisand, and Ian Holm have all reported fears of public communication.[4]

- Aristotle, Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, Winston Churchill, John Updike, Jack Welch, and James Earl Jones all had stutters and were nervous speakers at one time in their lives.[5]

Even if you could completely shut off these fear-response systems, which is the first thing people with fears of public speaking want to do, it would be a bad idea for two reasons. First, having the old parts of our brains in control of our fear responses is a good thing. If a legion of escaped half-lion, half-ninja warriors were to fall through the ceiling and surround you—with the sole mission of converting your fine flesh into thin sandwich-ready slices—do you want the burden of consciously deciding how fast to increase your heart rate, or which muscles to fire first to get your legs moving so you can run away? Your conscious mind cannot work fast enough to do these things in the small amount of time you’d have to survive. It’s good that fear responses are controlled by the subconscious parts of our minds, since those are the only parts with fast enough wires to do anything useful when real danger happens.

The downside is this fear-response wiring causes problems because our lives today are very safe. Few of us are regularly chased by lions, or wrestle alligators on our way to work, making our fear-response programming out of sync with much of modern life. As a result, the same stress responses we used for survival for millions of years get applied to non-survival situations by our eager brains. We develop ulcers, high blood pressure, headaches, and other physical problems in part because our stress systems aren’t designed to handle the “dangers” of our brave new world: computer crashes, micromanaging bosses, 12-way conference calls, and long commutes in rush hour traffic. If we were chased by tigers on the way to give a presentation, we’d likely find the presentation not nearly as scary; our perspective on what things are worth fearing would have been freshly calibrated.

Second, fear focuses attention. All the fun, interesting things in life come with fears. Want to ask that cute girl out on a date? Thinking of applying for that cool job? Want to write a novel? Start a company? All good things come with the possibility of failure, whether it’s rejection, disappointment, or embarrassment, and fear of those failures is what motivates many people to do the work necessary to be successful. It’s the fear of failure that gives us the energy to proactively prevent failures from happening. Many psychological causes of fear in work situations, being laughed at by coworkers or looking stupid in front of the boss, can also be seen as opportunities to impress or prove your value. Curiously enough, there may be little difference biologically between fear of failure and anticipation of success. In his excellent book Brain Rules (Pear Press), Dr. John Medina points out that it is very difficult for the body to distinguish between states of arousal and states of anxiety:

Many of the same mechanisms that cause you to shrink in horror from a predator are also used when you are having sex—or even while you are consuming your Thanksgiving dinner. To your body, saber-toothed tigers and orgasms and turkey gravy look remarkably similar. An aroused physiological state is characteristic of both stress and pleasure.

Assuming he’s right, why would this be? In both cases, it’s because your body has prepared energy for you to use. The body doesn’t care whether it’s for good reasons or bad, it just knows it must prepare for something to happen. If you pretend to have no fears of public speaking, you deny yourself the natural energy your body is giving you. Anxiety creates a kind of energy you can use, just as excitement does. Ian Tyson, a stand-up comedian and motivational speaker, offered this gem of advice: “The body’s reaction to fear and excitement is the same…so it becomes a mental decision: am I afraid or am I excited?” If the body can’t tell the difference, it’s up to us to use our instincts to help rather than hurt us. The best way to do this is to plan before you speak. When you are actually giving a presentation, there are many variables out of you control—it’s OK and normal to have some fear of them. But in the days or hours beforehand, you can do many things to prepare yourself and take control of the factors you can do something about.

What to do before you speak

The main advantage a speaker has over the audience is knowing what comes next. Comedians—the best public speakers—achieve what they do largely because you don’t see the punch lines coming. To create a similar advantage, I, like George Carlin or Chris Rock, practice my material. It’s the only way I learn how to get from one point to another, or to tell each story or fact in the best way to set up the next one. And when I say I practice, I mean I stand up at my desk, imagine an audience around me, and present exactly as if it were the real thing. If I plan to do something in the presentation, I practice it. But I don’t practice to make perfect, and I don’t memorize. If I did either, I’d sound like a robot, or worse, like a person trying very hard to say things in an exact, specific, and entirely unnatural style, which people can spot a mile away. My intent is simply to know my material so well that I’m very comfortable with it. Confidence, not perfection, is the goal.

Can you guess what most people who are worried about their presentation refuse to do? Practice. When I’m asked to coach someone on their presentation, and he sends me his slides, do you know the first question I ask? Did you practice? Usually he says no, surprised this would be so important. As if other performers like rock bands and Shakespearean actors don’t need to rehearse to get their material right. The slides are not the performance: you, the speaker, are the performance. And it turns out most of the advice you find in all the great books on public speaking, including advice about slides, is difficult to apply if you don’t practice.

The most pragmatic reason for practice is it allows me to safely make dozens of mistakes and correct them before anyone ever sees it. It’s possible I’m not a better public speaker than anyone else—I’m just better at catching and fixing problems.

When I practice, especially with a draft of new material, I run into many issues. And when I stumble or get confused, I stop and make a choice:

- Can I make this work if I try it again?

- Does this slide or the previous need to change?

- Can a photograph and a story replace all this text?

- Is there a better lead-in to this point from the previous point?

- Will things improve if I just rip this point/slide/idea out completely?

I repeat this process until I can get through the entire talk without making major mistakes. Since I’m more afraid of giving a horrible presentation than I am of practicing for a few hours, practice wins. The energy from my fear of failing and looking stupid in front of a crowd fuels me to work harder to avoid that from happening. It’s that simple.

Now, while everyone is free to practice—it requires no special intelligence or magic powers—most people don’t because:

- It’s not fun

- It takes time

- They feel silly doing it

- They assume no one else does

- Their fear of speaking leads to procrastination, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of misery

I know I look like an idiot standing in my underwear at home, talking to a room of imaginary people, practicing a presentation. When I practice in hotel rooms, which I often do, I’m worried at any moment the maid will barge in mid-sentence, and I’d have to attempt to explain why on earth I’m lecturing to myself in my underwear. But I’d rather face those fears in the comfort of my own room—with my own mini-bar, on my own time, over and over as many times as I wish—than in front of a real crowd, a crowd that is likely capturing my performance on videos and podcasts, recording what I’m doing for all time. There are no do-overs when you’re doing the real thing.

By the time I present to an actual audience, it’s not really the first time at all. In fact, by the third or fourth time I practice a talk, I can do a decent job without any slides, as I’ve learned how to make the key points by heart. This confidence that comes from practicing makes it possible to improvise and respond to unexpected things—like hecklers, tough questions, bored audiences, or equipment failures—that might occur during the talk. If I hadn’t practiced, I’d be so worried about my material I’d be unable to pay attention to anything else, much less anticipate what’s coming from the audience. I admit that even with all my practice I may still do a bad job, make mistakes, or disappoint the crowd, but I can be certain the cause will not be that I was afraid of, or confused by, my own slides. An entire universe of fears and mistakes goes away simply by having confidence in your material.

But even with all the practice in the world, my body, like yours, will still decide for itself when to be afraid. Consider, for example, the strange world of sweaty palms. Why would sweaty palms be of use in life-or-death situations? I’ve had sweaty palms only once, right before I was televised on CNBC. At the start of the taping, sitting on an uncomfortable pink couch, trying to stay calm in the bright lights and cold air, I felt a strange lightness in my palms. With the cameras rolling, I held up my hands to see what was going on. I had to touch them to realize they were sweating. The weirdo that I am, I found this really funny, which, by coincidence, relieved some of my anxiety. The best theory from scientists is that primates, creatures who climb things, have greater dexterity if their hands are damp. It’s the same reason why you touch your thumb to your tongue before trying to turn a page of a newspaper. My point is that parts of your body will respond in ancient ways to stress, no matter how prepared you are[6]. That’s OK. It doesn’t mean you’re weird or a coward, it just means your body is trying hard to save your life. It’s nice of your body to do this in the same way it’s nice of your dog to protect you from squirrels. It’s hard to blame a dog for its instinctive behavior, and the same understanding should be applied to your own brain.

Since I respect my body’s unstoppable fear responses, I have to go out of my way to calm down before I give a presentation. I want to make my body as relaxed as possible and exhaust as much physical energy early in the day. As a rule, I go to the gym the morning before a talk, with the goal of releasing any extra nervous energy before I get on stage. It’s the only way I’ve found to naturally turn down those fear responses and lower the odds they’ll fire. Other ways to reduce physical stress include:

- Getting to the venue early so you don’t have to rush

- Doing tech and sound rehearsal well before your start time

- Walking around the stage so your body feels safe in the room

- Sitting in the audience so you have a physical sense of what they will see

- Eating early enough so you won’t be hungry, but not right before your talk

- Talking to some people in the audience before you start (if it suits you), so it’s no longer made up of strangers (friends are less likely to try and eat you)

All of these things allow you to get used to the physical environment you will be speaking in, which should minimize your body’s sense of danger. A sound check lets your ears hear how you will sound when speaking, just as a stroll across the stage helps your body feel like it knows the terrain. These might seem like small things, but you must control all the factors you can to compensate for the bigger ones, the ones that arise during your talking that you cannot control. Speakers who arrive late, change their slides at the last minute, or never walk the stage until it’s their turn to speak, and then complain about anxiety, have only themselves to blame. It’s not the actual speaking that’s the problem; they’re failing to take responsibility for their body’s unchangeable responses to stress.

There are also psychological reasons why public speaking is scary. These include fears like:

- Being judged, criticized, or laughed at

- Doing something embarrassing in front of other people

- Saying something stupid the crowd will never forget

- Boring people to sleep even when you say your best idea

We can minimize most of these fears by realizing that we speak in public all the time. You’re already good at public speaking—the average person says 15,000 words a day[7]. Unless you are reading this locked in solitary confinement, most of the words you say are said to other people. If you have a social life and go out on Friday night, you probably speak to 2, 3, or even 5 people all at the same time. Congratulations, you are already a practiced, successful public speaker. You speak to your coworkers, your family, and your friends. You use email and the Web, so you write things that are seen by dozens or hundreds of people every day. If you look at the above list of fears, they all apply in these situations as well.

In fact, there is a greater likelihood of being judged by people you know because they care about what you say. They have reasons to argue and disagree since what you do will affect them in ways a public speaker never can. An audience of strangers cares little and, at worst, will daydream or fall asleep, rendering them incapable of noticing any mistakes you make. While it’s true many fears are irrational, and can’t be dispelled by mere logic, if you can talk comfortably to people you know, then you posses the skills needed to speak to groups of people you don’t know. Pay close attention next time you’re listening to a good public speaker. The speaker is probably natural and comfortable, making you feel as though he’s talking to a small group, despite how many people are actually in the audience.

Having a sense of control, even if it’s just in your mind, is important for many performers. If you watch athletes and musicians, people who perform in front of massive crowds nightly, they all have pre-show rituals. LeBron James and Mike Bibby, all-star basketball players, chew their nails superstitiously before and during games. Michael Jordan wore his old University of North Carolina shorts under his NBA shorts in every game. Wayne Gretzky tucked his jersey into his hockey pants, something he learned to do before games as a kid. Wade Boggs ate chicken before every single game. These small acts of control, however random or bizarre to us, helped give them the confidence needed to face the out-of-control reality of their jobs. And their jobs are much harder than what public speakers do. For every point Michael Jordan ever scored, there was another well-paid professional athlete, or team of athletes, trying very hard to stop him from scoring.

So, unless a team of presentation terrorists steal your microphone mid-sentence, or put up their own projector and start showing their own slide deck—designed specifically to contradict your every point—you’re free from pressures other performers face nightly. Small observations like this make it easier to laugh at nerves, even if they won’t go away.

[1] The Book of lists doesn’t say, but it’s likely their source was the 1973 report published by the Bruskin/Goldkin agency.

[2] If you combined this list to create scariest thing possible, it’d be to give a presentation, in an airplane at 35,000 feet, near a spider web, while doing your taxes, sitting in the deep end of a pool in the airplane, feeling ill, with the lights out, next to an escalator that leads to an elevator.

[3] It is debated what the motivations were for Jefferson’s small number of speeches. The Jefferson library takes a decidedly generous view: See http://wiki.monticello.org/mediawiki/index.php/Public_Speaking and Halford Ryan’s U.S. Presidents as Orators: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook, (Greenwood Press, 1995).

[4] From Conquer Your Speech Anxiety, Karen Kangas Dwyer (Wadsworth).

[5] The Francis Effect, M. F. Fensholt (Oakmont Press), p. 286.

[6] The attack of stomach butterflies are still a mystery. The best guess is it’s a side effect the stress response effect, that moves blood away from your digestive system to more important parts of your body for survival. Peeing and related excrementous efforts in your pants has similar motivations, plus the surprise effect of distracting whatever is trying to eat you away from your tasty flesh.

[7] There is a wide range from 10,000-20,000 depending on the individual. I wish you could know the number for the person sitting next to you on a plane before you start talking to them. From Michael Erard’s Um (Anchor)

————————

If you enjoyed the chapter, get the whole book:

- “A fresh, fun, memorable take on the most crucial thing: what we say. Highly recommended.”— Chris Anderson, Wired

- “Berkun tells it like it is… you’ll gain insights to take your skills to the next level.” — Tony Hsieh, CEO Zappos.com

- “Loved it! Informative & entertaining look at the art of public speaking.” — Garr Reynolds, author of Presentation Zen

- “Packed with Invaluable tips and advice.” — Tom Standage, Business editor for The Economist