The Amazing Invention of Braille

While studying to write the Myths of Innovation I read hundreds of accounts of how world changing inventions were created. While many of those stories are in the book, there are countless more worthy of telling.

Today is the birthday of Louis Braille, one of the inventors for the amazingly clever system of writing for the blind.

We forget that languages have a design. Good ones are efficient, robust, precise, easy to learn and fast to use. Most languages emerge over centuries and are shaped by culture, which makes it all the more impressive when someone successfully creates a new one in just a few years. (As an exercise: how you would you design a better language than English or your primary one? This was once an interview question my former boss Joe Belfiore used to use).

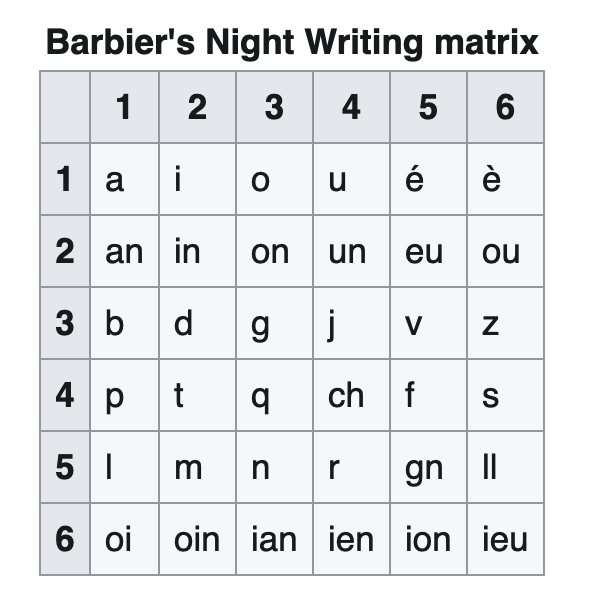

The story of the invention of Braille goes back to Napoleon and his desire to find a way for soldiers to safely communicate at night, silently, without light (as soldiers were spotted by snipers and killed when using lamps). A captain in the army named Barbier developed a system called night writing, but it was rejected as being too complex to learn and use. It required two values of 6, or 12 dots, to make a letter.

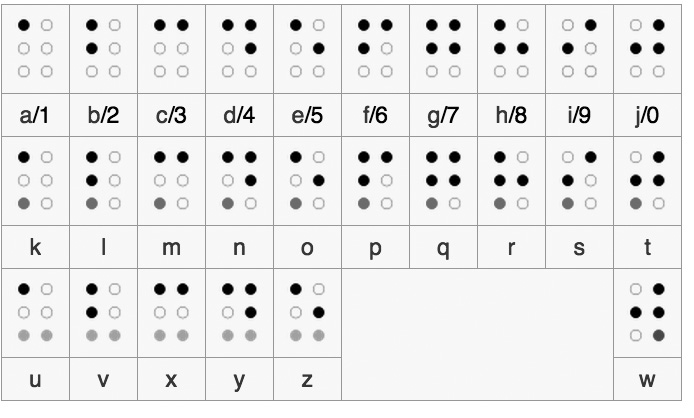

Louis Braille either met Barbier, or learned of his ideas, in 1821. In 1824, after years of work, Braille developed critical simplifications to the design, including moving from 12 dots to 6 per character. At first the system was used to literally translate each character, but as its use spread unique shorthands and contractions were added. Louis Braille was only a teenager when he finished the system, publishing it in 1829 and a revised, further simplified version in 1837.

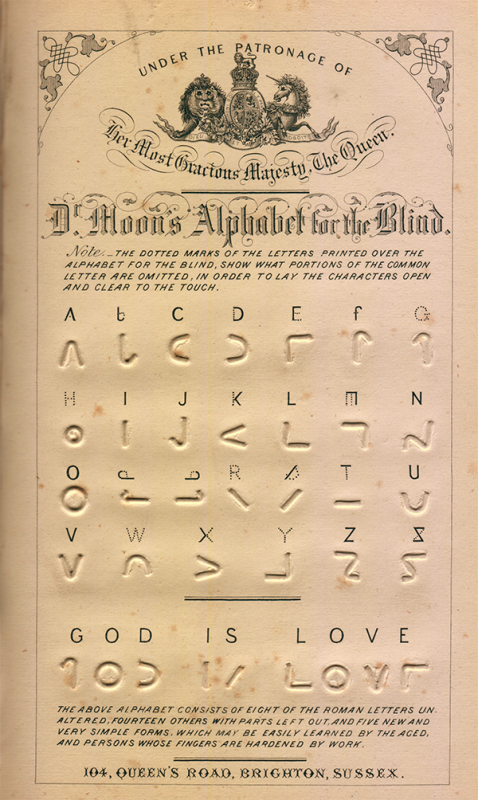

His own school didn’t adopt his system until 1854, after his death. During this time many variants were tried, including some based on the tactile alphabet, with letter forms printed raised on the paper. Louis Braille learned a system like this as a child. A popular one was called Moon writing (published in 1845), shown here.

These systems take up more space, but have the advantage of requiring less training and finger precision. For various reasons systems like this never became dominant. Slowly Braille’s system gained adoption in Europe and America by 1916.

The invention of the typewriter has some connections to Braille, as Pierre Foucault, a former student at Braille’s school, had an early prototype for a typewriter that printed Braille in 1847.

Technically Braille is the first system of digital writing, since the letters are encoded and can be manufactured and stored or printed mechanically. It is not a universal language however, as the encodings typically translate letters, demanding the reader know the language they are written in (see International Braille, which explains how in 1878 they standardized some elements for Braille across languages).

With the rise of screen reading software the use of Braille is in decline. But it remains a stellar example of design and invention.

[Minor edits and image improvements: 1/4/21 – all photos now creative commons from Wikipedia]

When my blind grandmother wrote to me or Mum she used a regular type writer. As it happened, it was after many lost years that my mother as a girl, informed Grandma that sighted people could type without needing to see the keys. Such a revelation!

When I wrote to Grandma I used a punch and a steel template. When she wrote to other blind people she used a Braille typewriter.

I had no idea about the typewriter connection. I love these historic invention stories so much – always a detail or two that surprises me, and reminds me to keep my mind open. Nice to hear you had some personal experience with Braille typewriters.

Nicely written article Scott! Braille readers from all over the world are thankful for Louis Braille and his contribution to the visually impaired/blind community. Like I’ve always said, “Braille = Independence” to its’ readers. Sighted or not; we all deserve the independence to educate ourselves :).