What I Learned At Hiroshima (In Photos)

I just returned from two weeks vacation in Japan. It was the first true vacation (no email, no lectures, no working) I’ve had in a long time. One highlight was the day trip we took from Kyoto to Hiroshima. We hadn’t originally planned to go to Hiroshima, or to be in Kyoto either actually, but when the opportunity arose I jumped at it. I love going to places that are well known in history, but that few people I know have ever been to (e.g. Little Big Horn).

The first surprise is Hiroshima is a large, pretty and healthy city. I didn’t have specific preconceptions, but I was somehow surprised to find a vibrant urban area of over 2 million people. The Peace Park is the historic area where many memorials and the Peace Memorial Museum, the name for the museum about the city’s WWII legacy, reside. It was easy to find the park as the Peace Boulevard leads from the train station straight to it.

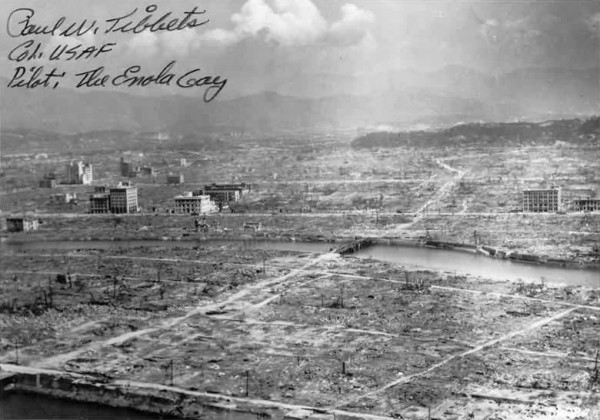

As the history goes, on Monday, August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m The U.S. dropped the first atomic bomb used during wartime, and it exploded, by design, 600 meters above the ground at Hiroshima. 80,000 people were killed instantly. Another 100,000 or more died within a year. The reason the bomb was detonated above the ground was to maximize the impact of the explosion. It was aimed at a T-shaped bridge, a bridge that still exists and is part of the park (I crossed it to get there).

The location where the bomb exploded is called the hyper-center and you can find it a few blocks away from the Peace Park. On an otherwise ordinary side street of parking lots and office buildings, there’s a small monument describing the significance of where you’re standing.

One reason I wanted to go to Hiroshima was to stand in this spot. A thousand questions were on my mind as I stood there. It seemed so ordinary a place in the moment, but looking up and imagining that bomb falling and what it would do was inexpressibly complex. It was mostly horrible, but wonderful for intellectual curiosity reasons, to be able to stand there.

The first building hit by the bomb was this one, called the A-Bomb dome (formerly called the Hiroshima Commercial Exhibition Hall). They debated whether to restore it or not, but chose to leave it as a monument to what happened. It has been preserved to look like how it looked right after the bombing.

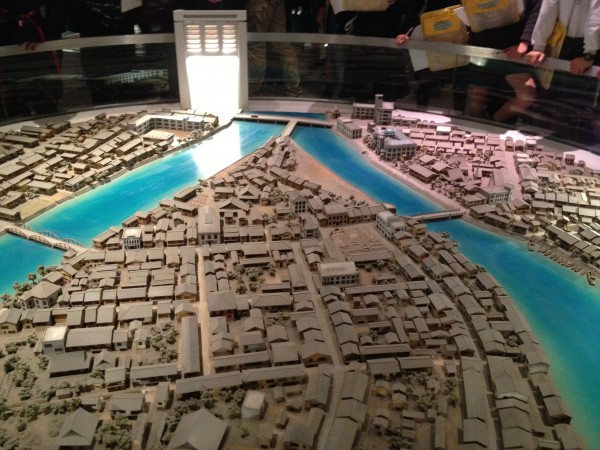

At the peace museum are detailed diagrams and models of the city, before and after. Here’s what it looked like before the bombing. Notice the t-shaped bridge at the top. To its right is the A-Bomb dome.

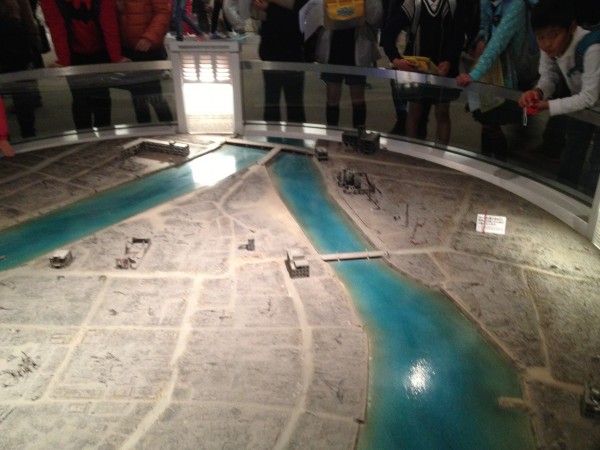

And here’s what it looked like after.

The biggest and most pleasant surprise from my visit was how the Japanese have converted a horrible episode from human history into something positive, without skipping past the difficult parts. The peace museum tells a balanced story of WWII and the bombing itself, leading visitors through rooms about the current nuclear weapons treaties and the effects of nuclear radiation on citizens.

But the park is called the Peace Park and Memorial for a clear reason: they want to use their example to prevent similar horrors from ever happening again and they did an excellent job of making that the clear theme in the experience of visiting the place. They did a far better job at this ambition than any other historic war site I’ve seen, and I’ve seen many.

It seems mandatory that young students visit the center, as they were there in busloads. The primary frustration I had with the Peace Memorial Museum was having to navigate around gangs of Japanese kids. Even outside the museum we met many groups of children in the park and they were curious about foreigners, which was great to see. I’d say hello as they passed by in groups, and they always laughed and waved back at me.

Many of the younger students had assignments to talk to foreigners and practice their English. They asked me where I was from, what my name was, and what thoughts I had about the museum and world peace. It was a highlight of the entire trip to meet these children and talk with them for awhile.

One section of the park is dedicated to the story of Sadako Sasaki, a young survivor of the blast who was hospitalized as a young girl with radiation related health issues. She believed in the legend of 1000 cranes, that if she folded 1000 paper cranes, she could have any wish granted. Her story became a legend after her death and thousands of children have made paper cranes to honor and remember her. There are display cases with some of them in the park near a statue dedicated to her and other children who were victims that day.

There’s an online petition, sponsored by the museum, that calls for the reduction of nuclear weapons in the world. You can sign it here.

Great post, such an interesting visual journal of the visit. Thanks for sharing photographs along with the experiences.

Not long ago I came across a video showing a lapsed time map of nuclear tests in the world (it has around 3 million views on YouTube), which is just shocking. The amount of nuclear testing we do, especially USA and China, is ridiculous. Often done in the oceans with huge loss of marine life, and repercussions for our future generations the scale of which we can’t fully fathom yet.