The Last Jedi and Suspension of Disbelief

[There’s no askberkun post today – hope you enjoy this timely essay on films and expectations. There are no spoilers about The Last Jedi, but I’ll allow them in the comments.]

“The writer is always tricking the reader into listening to the dream.” —Joan Didion

We love or hate films based on what we expect of them. It’s easy to blame a movie’s creators, as we are their customers, but in reality half the work is ours. Do you want realism or an escape? Do you want to be satisfied or challenged? To think or to laugh? What rules from real life must be followed or do you want broken? Too often we leave it until we’re midway through a movie to realize that what we wanted wasn’t what we thought we wanted and we rarely blame ourselves for that mistake.

Two decades and ten films into the world of Star Wars I find my expectations hard to manage. I thought Rogue One, The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi were good “Star Wars films” but what does that even mean? It’s hard to watch any of these films now, new or old, without thinking at various moments about how it ties together, or cuts against, the history of the series. This is part of the fun, but it’s also a trap. These are now meta-movies. They are, as Lucas intended, serials, like the cliffhanger shorts he was inspired by, but is that what I really want watch? I’m not sure.

It’s hard to experience any event, or character, no matter how well done, in a Star Wars film as if it exists in it’s own time in it’s own ‘real’ universe. The burden of Star Wars (and most film series than span generations like Terminator, Indiana Jones or Spiderman) is any story you are watching is burdened by narrative masters that lurk in the shadows off-screen, in our memories. And franchise reboots only complicate the expectations game, playing on and against our expectations in both interesting and frustrating ways. I want to just watch the film in front of me, free from too much context, but that’s not the world these films put us in anymore.

All movies depends on the audience accepting a departure from their daily lives. We know these are actors on movie sets inventing a false reality. Mostly this departure is what people are paying for: an escape of one kind or another. Even the act of sitting in a full theater itself, sharing an experience with others, is something we don’t do often in life anymore. Consider the ritualistic decent into shared silence as the previews end and the feature film begins: when else in life are we in grand rooms with hundreds of strangers who all agree to respectfully share the silence? It’s evidence that everyone has reverence for the powerful shared escape of film.

Coleridge coined the term suspension of disbelief to describe the desired state of mind a reader, or viewer, needs to have for the work of art to function. But the question is: who should do the greater burden of achieving this state of mind? The creator or the consumer? We assume it is the creator, and they do have the lion’s share, but if the consumer is not in the mood for Shakespeare, or Amy Schumer, is there anything Shakespeare (or the director of the particular play) or Amy Schumer can really do about it? Films, like most commercial art, make promises in their advertising and marketing, but our expectations, when we sit in that chair and the film begins, are still are own.

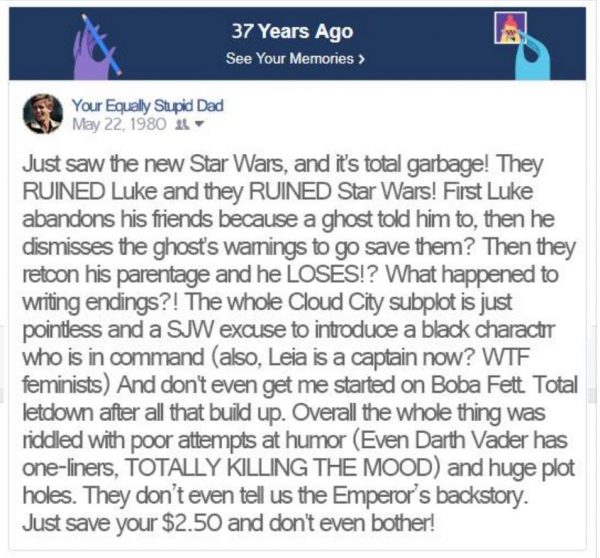

More to the point about Star Wars, these are not realistic films. Most of the battles, plots and plans even in the original triology don’t hold up well to even the most basic questions (see: we dare you to explain Luke’s plan). It’s the suspension of disbelief that holds most viewers back from ever asking these kinds of questions. Which means the endless arguments about plot lines and holes, boneheaded choices by lead characters, or story arcs that go nowhere reveal the arguers chosen position on the spectrum of disbelief suspension: they only want to disbelieve so much. Which translates into something like “YES, movies with time-travel, or zombies, are fine. And in Star Wars, it’s OK that a long time ago spaceships somehow operated on different principles of physics, a power exists that unifies the universe in such a way that people can use it move objects with their minds, but NO a Starkiller base couldn’t possibly work.” Even when we criticize the inconsistencies of a film, we forget that we’re partly responsible for the rules we’re expecting a fiction to be consistent with.

Part of the value, in fables and fantasy, of bonehead choices and challenges to logic is the gift of superiority it gives to the audience. It’s straight out of the classic soap opera and hero myth narrative playbook to inspire the audience to judge mistakes, to debate flaws, and to be enraged by them. “What! They had an evil twin?” is well known as one of many standard genre tropes for soap operas and films, but even the Iliad expects us to accept the plausibility of a (successful) Trojan horse, the power of Helen’s beauty, and even begs the reader to criticize the hero Achilles (although perhaps not the supernatural nature of his powers).

And each person has their own, often subconscious, list of expectations they never want violated. Some of these rules, like say, the limits to how the force works, or what is allowed to happen to certain characters, feels fair as it’s defined by the legacy of the films themselves. If James Bond could suddenly fly, or Wonder Woman turned out to be an an alien robot from the future, the shock would be understandable (although comic books notoriously introduce shocking plot lines that violate rules). But if a story that has always had the same flaws continues to have them, and there is outrage, who’s problem is it really?

For all the worship of Campbell’s Heroes Journey, a model of storytelling Lucas claims to have used in on his final drafts of the original Star Wars, there’s something shallow about it’s advice. Stories based on universal themes, that are told in a universal way, tend to overly simplify the complexities of good, evil, love and hate. There are rarely “bad guys” and “good guys” in life in the way these stories suggest (and to be blunt, the evil of the bad guys, and good of the good guys, in Star Wars is never explained well, as explaining it is not a strength of this idiom. Luke and Rey could just as well have been “evil” given their rocky starts in life). Is this a problem or an advantage? Well of course it depends. Do you want a soap opera about a far away galaxy today, or a factual memoir by a refuge from a war torn country? A slapstick comedy or a family drama? Do you like the suspension of disbelief mythology and fantasy require, or do you want the down to earth reality of a good documentary about a topic you know well?

One meaning of the word idiom is a mode of expression, or a set of rules for what an audience can expect. Star Wars from the beginning was a fairly tale, a space opera, by design, not caring much about science (e.g. spaceships can’t make bank turns in space, nor make sound), logic or military strategy. Those attributes might be expected in a war movie like Saving Private Ryan, but that’s not the kind of universe Star Wars was created for and thrived in. Arguably a great film transcends idiom: it magically draws you into it’s world regardless of your preconceptions, boosts your suspension of disbelief through filmmaking craft, but that is harder to do in story that’s being told in installments over 40 (or more) years. Which leads to the question: if you saw a random Star Wars film without knowledge of any of the others, what complaints would you have?

Running jokes about how stormtroopers have terrible aim are good because they strike at a truth about the series and the genre. Another is the how heroes regularly pilot spaceships, including freighters, at high speed in impossible turns (that violate physics) through jagged landscapes and spaceships, ones they’ve never seen before, defies any understanding of science or human performance (assuming of course these characters are human at all). Flash Gordon (a major Lucas influence) had similiar problems and so does Indian Jones or The Fast and The Furious or any story with an action hero as the star, as if they die the series ends, but if there is no drama, our disbelief is broken, or we’re bored.

The grand trap might just be that as the age of Star Wars’ first audience matured into adulthood, we backfilled more mature expectations into it. The mythology shifted into religion as the literalness adults crave took control over the generous imagination of youth. For this reason we take seriously story details that were never quite meant to be taken that way. In Greek Mythology, the god Athena was born from the head of Zeus, but to my knowledge there is no reddit forum yet that debates how impractical (or not) this mostly metaphorical plot note might be. We criticize movies that explain too much as having too much exposition, but in fantasy if you start explaining things you chip away at the unreality of the whole thing.

The Star Wars prequels were of course terrible in many ways, but one perhaps noble failure was it’s attempt to make the Star Wars universe sophisticated, nuanced, mature, something more than a fairy tale. Lucas did this of course in direct conflict with the originating idiom the films were born in (most notably the tragic introduction of midi-clorians), but was he wrong to try? I’m not sure. Had the film’s fundamentals of plot, writing and acting been sound, the (now) adult fan base might have widened their suspension of disbelief to allow for more mature kinds of storytelling, even within the context of a fairy tale. But now we will never know, and the series is burdened by the resulting damage (in a similar way The new Star Trek and Hobbit films have burdened their series too).

I found The Last Jedi to be both frustrating and liberating. As a movie I think Rian Johnson and his team did a fine job. They made a “good Star Wars” film. Given the truly otherworldly baggage they inherited they both took more risks, and yet respected the idiom, enough that I’ll keep watching, and for films of this kind I’m not sure what other opinion there is that matters.

The lesson in all this about suspension of disbelief is that it can be thought of as an exercise of imagination. For every plot flaw, every stupid choice a hero makes, for every consistency violation, we can play the generous game of filling in the gaps ourselves. Let’s assume there is a good reason for this, and if I need it I can create one myself, even if it’s not shown on screen. Our brains do it for us most of the time when we sit in a theater, but I advocate helping it along. This can be far more fun than tearing films apart (which is certainly fun too) as we go to theater hoping to escape, rather than to devise ways to ruin the attempt.

But of course we don’t go to movies to obtain homework. I agree we should expect much from the people who take our money for their movies, books and art. But in the end we choose which tickets to buy. By now we know very well what, at its best, the world of Star Wars can do. And there is far more pleasure to be gained by offering generous suspension of disbelief and by matching our expectations, to the idiom of the movie we’re choosing to go see.

[Last Jedi spoilers are allowed in the comments: so view them at your own risk]

There is, I feel, a similar dynamic at work. in a way, it’s a make-believe environment and if we all play along then all goes well, but frustrations mount when the rules if that environment bend too much and we don’t know what’s going on.

I really enjoyed this film. saw it twice. I will see it many more times.

I thought the film was fine – I really find it hard to watch these films just as films – so there were parts I thought were frustrating, parts that were brilliant, but more than anything I’ve resolved to see it as a soap opera and can’t take it all that seriously anymore. I’m *almost* more fascinated by the commentary around the films (what they do or don’t mean, what is good or bad about them, etc.) than the films themselves.

I would agree that being a little more generous with our suspension of disbelief might help with what someone might think is a problem in a film, as in Snoke being so powerful that he can create force-connections between two distant characters (which Palpatine couldn’t do) yet he wasn’t able to see a future in which his apprentice tries to kill him (an ability Palpatine had). However, there is the bending of rules (as in Chris Mahan’s comment) and there is the inconsistency of rules.

For example, the use of shields in the Star Wars universe is inconsistent. A planet in an earlier film has shields that prevent bombardment and entry by enemy ships, but at a later time in history, the planet the Resistance flees to doesn’t have this ability.

Or, some ships have shields that protect against laser weapons but can be sapped of strength (the Millennium Falcon), while much bigger ships don’t have this. The ships in the fleeing Resistance fleet have shields that protect them from distant bombardment, but not close bombardment. A Super Star Destroyer may have shields that prevent laser damage but can’t stop concrete objects (bombs) from destroying it. If such a thing were possible, why weren’t such bombers used by both sides in previous wars?

Many ‘hardware’ choices in The Last Jedi seemed picked for effect rather than logic. Look at those craft on the salt planet, which somehow need stabilizer fins stuck in the ice in order to ‘fly’ properly. Huh? It makes for great spectacle (the red on white visuals) but is totally impractical. Then there is the plot necessity ofResistance ships running out of ‘fuel’, something that has never been mentioned in the ‘canon’ before and seems highly unlikely with the assumption of antimatter drives (or whatever has been the engineering concepts implied before). Where do ships get their fuel from, planetary gas stations? What a crock!

If these choices are considered to be within the ‘idiom’ of the film universe, then fine. Or, if they require ‘generosity’ of suspension of disbelief just so one can enjoy the effects of the choices, again fine. For me, however, such choices drop me out of the ‘fictional dream’ of the film (using John Gardner’s term). They feel like direct manipulation for viewer effect, not storytelling choices that produce an organic effect for the reader.

Maybe I am being picky, but I feel we (viewers, reviewers, critics) should be allowed to criticise the makers of films for their choices. We should be able to apply standards to the film-making and call out flaws in the resultant products. To say we should be generous in our approach to the idiom of a film and that our expectations need to be managed could be seen as a type of ‘victim blaming’. It’s as if the reason you don’t enjoy the film is that ‘you don’t get it’. I would agree we should be mindful of our expectations when engaging with cultural products, but I also feel that it is the creator’s job to create a consistent, engaging, compelling ‘fictional dream’ that we can enter and enjoy, given the ‘genre expectations’ around the product.

I wouldn’t say you or anyone is being picky – it’s really about what you want from a film. It’s great fun to pick a film apart – I do it all the time and have certainly done it with Star Wars.

My point specific to these movies is that they’re all easy to pick apart – they all, even the original trilogy – have terrible gaps in logic, science, planning and common sense. We choose to overlook many of them because we don’t want to (escape!), or because we’re drawn in by characters or drama (emotion!) or the filmmaking craft is good enough that we don’t notice, but you don’t have to look hard to find them.

I’m fascinated by how all of us, myself included, have our own definition of what “the rules are” – they really do differ quite widely from person to person – even though we’re all watching the same film(s).

Great comments all! Had Lucas stopped making Star Wars films after Return of the Jedi, it’s doubtful that so many fans would be discussing the internal logic and “rules” of those films today. But he didn’t stop, and Disney appears to be just getting started.

Watching the first film with my children now, I find the inconsistencies and prop gimmickery quite humorous. I can’t help laughing when Luke, after surviving an ambush of Sand People, regains consciousness and immediately recognizes Ben Kenobi even though it is clear he has never met Ben. What is more, his uncle Owen has explicitly told him that Ben “doesn’t exist anymore” and died about the same time as his father. Does Luke know his uncle to be a liar or is he generally that good at recognizing perfect strangers? And why do Storm Troopers wear that ridiculous, white armor if it doesn’t provide any special protection? A simple phaser blast passes through it like a hot knife through butter.

But my children don’t notice the irregularities inherent to Lucas’ galaxy. They have watched only the first two original films, and they love them just like I did as a child. Any threat to the suspension of their belief would seem to be far, far away. But, how long will it take before the obvious gaffs jump off the screen at them? Episodes 1-3 introduce too many inconsistencies and bad plot choices. Midi-clorians? A flying R2D2? One could hardly blame Lucas for making more Star Wars films, but as Earl suggests, we could have and did expect more from Lucas even while generously offering the best of our imaginations. Here’s a thought… Lucas set a precedent for revising previously released films, so it is not entirely unthinkable that the whole Star Wars universe might one day be reworked, revised, and remade. In a way, the original cast of characters transcends the franchise.

As a child watching the CBC in the mid-1960’s I was quite able to believe in plain little box that was big and fancy inside, and that went through time AND space. Only years later did I realize that adults have a less generous imagination.

I groaned when STNG had matter manipulation, like magic. Yes I know, ST could manipulate matter for the teleportation (transporter) room, but ONLY for that, only as a plot device to save time. ST made perfect sense to me.

I definitely agree about the Star Wars prequels but I’m looking forward to seeing the new film again. Interesting blog post as usual Scott!

Thanks Tom. Seeing it again made me realize how long its been since I saw any Star Wars film for the first time (well, The Force Awakens, obviously). They live in our memories in an unusual narrative dimension where the familiarity with the story is easy to confuse with it’s quality.

I really can’t judge how good or bad a film Star Wars: A New Hope is. I’ve seen it too many times to evaluate what is a true response vs. what is a response to a pleasurable memory of a response to actual drama where I don’t know what’s happening. But I think I’ve finally accepted that this is OK: that there is pleasure in these films anyway, even if some of it is about the layers, the history and the echoing of traditions or rejecting them.