At UI13 I had the chance to chat with Dana Chisnell of usabilityworks.net, who has been working on ballot design and usability for the last few years. She agreed to answer some questions about what’s happened since 2000 and 2004, and what we should expect from ballot designs this week.

SB. What is the state of the art in ballot design? Which states have done the best job of learning from Florida? Which states have done the worst?

DC: The state of the art in ballot design is in a beautiful document published by the US Election Assistance Commission called Effective Designs for the Administration of Federal Elections (PDF). It includes detailed design specifications for printed ballots of various types, all based on user research and usability testing. It’s available for free here:

The objection that states and counties have to the designs in the EAC report is that they pay no attention to cost. For example, the report recommends using 2 colors (usually black and blue), but adding color is expensive. Also, making the type larger or opening up the layout of printed ballots often means making the ballot cards longer, flowing over onto the back side of a ballot card, or printing more cards. The printing is expensive, and with more voting by mail, the postage costs go up.

Several states have implemented as many of the best practices as is practical. Oregon — where all voting is by mail — was on the forefront. But other states such as Nebraska have embraced the guidelines. Florida’s Governor Charlie Crist took as one of his first acts after he was elected to warehouse all of the electronic voting machines and forced all the counties to go to printed ballots after the November 2006 election. One of the drivers to that change was a huge undervote in congressional district 13 (Sarasota and Charlotte counties) in 2006. Typically, between 1 and 5 percent of voters don’t vote on any particular race in any given election. But in that election, somewhere between 11 and 15 percent of voters did not vote for a representative to Congress. There weren’t any security issues. The programming was fine. It all comes down to a ballot design problem.

There are still serious problems with ballot design, though. Ohio’s secretary of state sent out a ballot template that included one best practice — putting the instructions in the top left of the ballot card — but then split the presidential race across two columns. We know from previous elections that people either don’t vote for candidates in the space under the instructions, or they overvote by voting for someone in the first column and in the second column, which would mean than neither counts.

A few places have started conducting usability tests of ballots before they’re printed or loaded into voting systems: Sarasota and Duvall counties in Florida; Los Angeles County; Marin County, California; Clark County (Las Vegas), Nevada; and the state of New Hampshire. I take this as a sign that there is hope for the world.

SB. Typically whose job is it to actually design local and state election ballots? Is there any training required to do this job?

It’s different in different places. In many states, the secretary of state issues a ballot template. But it always comes down to local election officials at the county level to implement the design. Often the local election official outsources the actual layout to a vendor or to the manufacturer of their voting systems because the layout software is wicked hard to use.

There are lots of layers of training. The first is to know intimately the election statutes for the county and the state. It seems whacky, but in most places things like type size, capitalization, and the language of instructions are all defined in a law. The number of languages that ballots must be available in is also legislated.

Next, you have to know the constraints of the voting system you’re using. For example, if your county uses an optical scan system — the type where the voter fills in bubbles or connects the ends of arrows — the choices on the ballot must line up with tick marks or registration marks on the edges of the cards, which definitely constrains leading or line height.

Finally, there are dozens of different types of districts in every county. Where you live in Washington State, there are hundreds of combinations of local districts: school, water, cemetery, conservation — the list goes on. So there can be hundreds of variations of ballots within a state or county (if it’s big enough). A given county could issue one ballot for all or as many as 300 variations on a basic ballot because of the different district combinations.

But to answer your original question, there’s usually one person in the county who is responsible for the design of the ballot. And then a few other people do reviews. Usability testing is a really new, new thing in the world of elections.

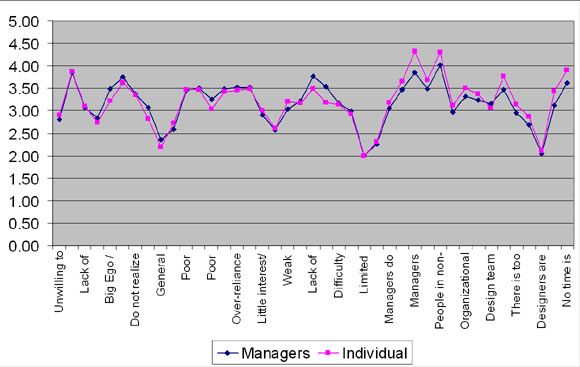

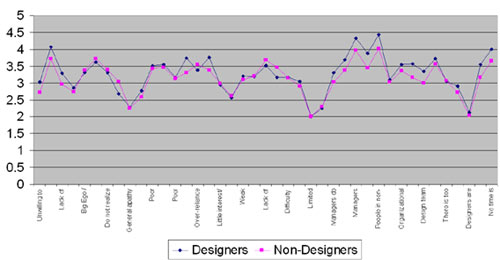

SB. How difficult has it been to get legislators and politicians to understand the value of design and usability? What tactics have worked best? Has this been different in your experience than working with business executives?

Some of the problems are the same in the public and private sectors. How do I fit this into my already-tight election cycle? How do I get design and usability for free (or for cheap)? What if there are hideous things that I don’t have time to fix?

In the end, it comes down to two things: a) the possibility of getting bad press; and b) how much will it cost if something goes wrong and we have to do recounts (which usually also involve multiple law suits).

As a reaction to the “butterfly” ballots used in the 2000 general election, Congress passed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA), which mandated replacing old voting systems. Most of the new systems were electronic voting systems with touchscreens. Local elections officials loved this idea. It was thought that computers would be safe and reliable. Soon the discussion was hijacked by security concerns. The original problem — ballot design — is still being addressed and solved.

It’s as if legislators have had to learn the hard way. We’ve just been running one gigantic live usability test over the last eight years. As problems are more closely identified and eliminated, the more nuanced things come to the fore.

It all matters these days because elections are so close. When the margins were wider, there was much more room for error in design. Now, not so much.

SB. What is your opinion of electronic voting? Does it solve any of the important problems we have?

Advocates for people with disabilities like electronic voting very much. And there are a lot of good things about electronic voting for people with disabilities. It is *amazing* to hear stories from people who have never been able to vote independently before talk about marking and casting their own ballots.

BUT from a design point of view, I think that some of the problems are multiplied. For example, not only do you have to consider type face and size, color, line length and height in the visual design, but now you also have to deal with navigation and interaction issues that just don’t exist on the paper versions, as well as error messages and instructions for using the user interface. For example, on most electronic voting machines, to change a selection a voter must deselect the choice already made before she can make a new selection. There are good reasons for doing it this way, but it isn’t conventional (no ATM or ticket kiosk works that way) and there are no instructions on the screen.

SB. Have you examined how other counties design their ballots? Where does the U.S. rank in terms of ballot usability?

The US has some very special problems. In other countries, the whole country votes on the same ballot. Unless there is a referendum, there are rarely questions or propositions on the ballots. So it’s easy to be consistent from location to location.

But other countries have to deal with things we don’t normally think about in the US, such as low literacy. In India, Africa, and South America, ballots have pictures of the candidates on them or symbols for the parties or both. In those places, they also have to be concerned with bandits or terrorists forcing people in far off, rural precincts to vote the way the bandits want them to vote. So there are panic features of the voting systems that allow them to be shut down and secured easily.

SB: What can designers and usability experts do to help support improving ballots in the future?

Sign up to be poll workers. It is estimated that 2 million poll workers will be needed for the election on November 4. There’s nothing like observing real people use a design in real time. Take note of the types of questions voters ask.

Sign up to be a temporary worker counting ballots or doing canvasses after the election. If the jurisdiction used paper ballots, you’ll be able to see post hoc how voters marked them (the variety is amazing).

Learn everything you can about ballot design issues. I’ve included one link to the Effective Designs report above. The Usability Professionals’ Association also sponsors a Usability in Civic Life project that works on ballot usability and accessibility issues and maintains a blog about issues and findings. There are also some interesting reports from research conducted by the National Institutes of Standards and Technology at vote.nist.gov, not to mention hundreds of blogs about voting, election administration, voting system security, and so on.

Visit your local election department (but wait until December or after). Ask for a tour. Interview the election director. Volunteer your time to do small things, like a day of asking people who show up at town hall for other things to vote a ballot that is in the design process while you observe them. Show people voting instructions and ask them to circle or highlight anything that isn’t clear or that they have questions about. That sort of thing.

SB. For fun: in all the usability studies you’ve run regarding voting, what’s the most tragic failure you’ve seen by an ordinary citizen in a voting booth?

Voting a completely empty ballot on an electronic machine because the touches on the screen did not register. When we asked the participant how confident she was that she voted as she intended, she said she was very confident. When we asked her if she had noticed that the things she touched on the screen did not change color (as the instructions said they would, as she had read aloud to us), she said, “That’s the way computers work.”

The New kings of Nonfiction

The New kings of Nonfiction