Thoughts on Death to Bullshit & Information Overload

I recently watched Brad Frost’s interesting talk Death To Bullshit (slides). He takes strong positions about information overload and advertising, and with down to earth charm, explores the evidence he’s found.

Since I’ve written before about detecting bullshit, calling bullshit on gurus and BS social media experts I had commentary to offer. You’ll get even more pleasure from this post by watching his talk first, but it’s not required, and since we’re talking about information overload I doubt you’ll do it now. I’ll remind you later too.

I had 5 points in response.

1. Our brains are primarily information filters

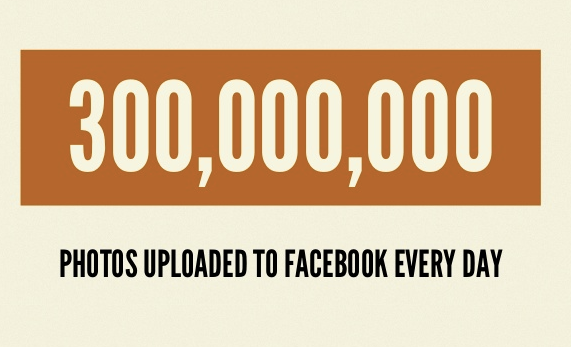

Frost offered various statistics about the ridiculous amount of information we produce, like this one:

And these facts are always stunning.

What Frost overlooks is the existence of these photos doesn’t obligate me to look at any of them. On the day you were born there were already thousands of books in existence you will never hear the name of, much less read. Same for magazine articles, films or plays. Or whatever it is we’re supposed to be intimidated by.

My point is my brain, sitting here at my desk, consumes only information I put in front of it, or that happens to land within range of my senses. How much more there is in the universe is irrelevant.

And our brains primarily filter information out:

- Our field of vision is about 140 degrees, meaning we’re blind to 220 degrees. We’re mostly blind.

- We don’t see infa-red light, or ultraviolet, or most light actually.

- Dogs, cats and most animals hear and smell a much wider range of information than we do.

We are information filtering machines. We automatically filter out far more than we could possibly consume, even when we consume more than we should. Even when we feel stressed and overwhelmed, our brains are filtering out far more than we take in.

2. Overload depends on what you consider information

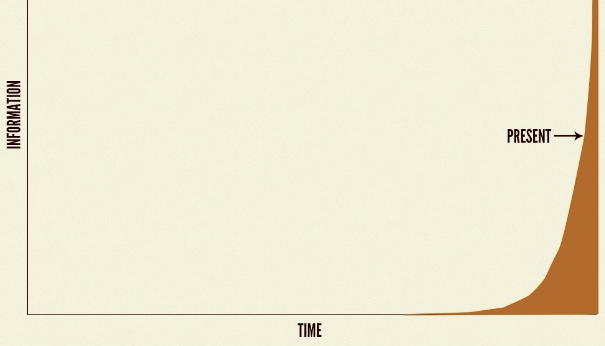

Frost offers this scary chart. It’s accurate if you define information, as we commonly do, by only counting man made information.

But consider taking a walk in the park.

For most of us a walk in the park is relaxing. There’s is plenty of information in nature, but we don’t experience overload. Why? In part because we’re just visiting, but also because we’re ignorant of all the information there. If you were a botanist, arborist, or entomologist you’d find loads of data in every patch of grass, every tall tree, and every ant hill. Even a child with a magnifying glass can spend hours in a small patch of forest, examining the fascinating amounts of information in every strip of bark, spider web or pine cone.

There are amazing amounts of information everywhere depending on what you know, what you choose to look at, and how you choose to look at it. Overload then is a matter of your attitude towards the information. Does it scare you? Does it excite you? Does it fill you with stress, or with desire? Your information attitude matters more than the amount of information around you.

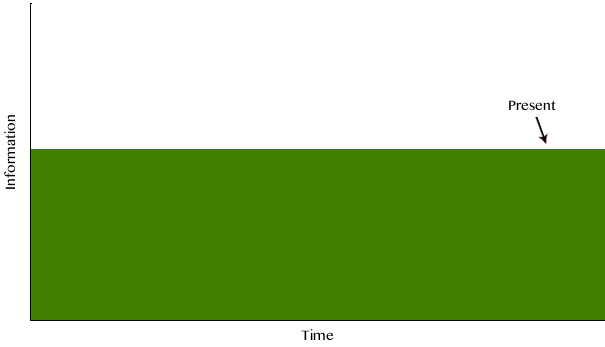

One popular theory about our universe is that there is a fixed amount of matter in it. All that changes over time is the state and position of particular atoms. For example, every molecule in you came from a star and has existed for millions of years. If you considered atoms as information, you could make a chart like this one below. The net information in the universe might be fixed:

This seems strange of course. And boring. It doesn’t make humans seem important, which is why we rarely think about information this way. But if you do, even for a moment, you realize our assumptions about what information is, and therefore, what overload means.

Neil Postman wrote “Information is a form of garbage” and I agree in a sense. It’s cheap. It’s everywhere. Information without knowledge or wisdom has little value, despite how often we’re sold on buying things because of the volumes of information they contain. We always have a surplus of information around us and we should be aggressive about ignoring it from sources we don’t trust.

We are compulsive information hoarders. We still pretend information is scarce. It isn’t. It never was. Even if you limit it to human produced information, for the last few centuries if you could read and had a nearby library, you had several lifetimes of information available to you.

3. There was information overload before our grandparents were born

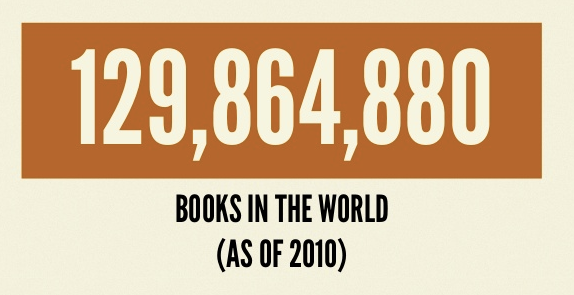

As an author I’m constantly reminded of intimidating statistics on the competition. Tens of thousands of books are published in the U.S. every year, and as Frost pointed out, there are several hundred million books in the world.

But what’s overlooked is that on the day you were born, or your grandparents were born, there were already more books in print than you or they could possibly read, even if you or they dedicated your entire lives to reading books. The same is true for places on earth to visit, languages to learn, meals to try, dances to dance, and on it goes.

In this sense we are born “information overloaded.”

An obvious question then is: why the hell would we care, today, about information from ordinary dead people we’ll never meet? We shouldn’t. And the same goes for the millions of people we don’t know in the present who create these massive piles of information. The presumption of all information should be it’s unworthy noise. Frost references Sturgeon’s law, that 90% of everything is crap, and this should warrant a general lack of interest in the majority of information produced by anyone, anywhere.

Our true disorder is information insecurity: we are insecure about what we have and compulsively consume to fill a hole that doesn’t exist.

4. People’s capacity for bullshit is constant

The later half of Frost’s talk is critiques of bad design and advertising as examples of bullshit. He closes by offering two claims:

- People’s capacity for bullshit is diminishing

- It’s harder and harder to be an asshole

These are tough claims to support. They’d require their own presentations.

I don’t agree with either claim, but my position isn’t any easier to argue for. People’s capacity for bullshit is as high as it always has been, on average, across our species. Freedom of information in democracies has certainly improved access to and interest in “the truth”, but technology is great for bullshit. Twitter, Facebook and the web are filled with it, as media transmits lies just as effectively as truths. Tech progress is indifferent to bullshit. And of course one person’s bullshit might just be some other person’s wisdom.

Much of the bullshit we consume comes in soft, sugary chunks we’re all too happy to consume. We like to hear what we like to hear. We prefer comfort to discomfort, and well crafted bullshit goes down far easier than tough truths or complex realities. There’s great profit to be made from being the kinds of assholes that produce and sell bullshit and as long as that’s true, there will be plenty of people working in BS production.

5. The final truth is we control the off switch

It’s is righteous to criticize producers of garbage sold as wisdom. It’s good to share advice that helps with the challenges of finding signal in the noise.

But these problems are largely self-inflicted. We flip the on switch for every device we feel overloaded by. And we can flip them off too.

A fascinating exercise for complaints about overload: ask, can I turn this off?

Unsubscribe from that email list. Watch one less television show, subscribe to one less podcast. Prioritize time offline with people you like and love over other things. Often our first response to this suggestion is an impulsive, self-righteous defense for why we really really really need each and every thing we don’t have time to consume, even in multiple lifetimes. This should reveal our insane and self-inflicted habits of destruction. The first step is to acknowledge who really has the problem. It’s us, not them.

See Also:

[h/t to Ario for pointing me to Frost’s talk]

I spend at least 20% of my time deciding what to filter out and not pay attention to. Frequent conversations between me and the scientists I manage involve me saying, “Do I really need to know this?” Exclusion of thoughts, plans, ideas, etc, is as important–if not more–than inclusion.

That’s wise to intentionally avoid things. It’s easy, especially as a manager or leader, to assume you have to know everything.

The only way to find out what you really need, information wise, is to periodically turn things off. It’s surprising how little value most daily news and information is in our ordinary lives.

It’s easy, especially as a manager or leader, to assume you have to know everything.

The single most difficult aspect of transitioning from being a bench scientist to being a leader of other scientists is letting go of the need to be on top of every single solitary detail. Because, of course, that personality trait is exactly what made you a good bench scientist in the first place.

Here’s my selectivity: I’ll soon consume Frost’s talk as a multi-task, with my priority on resting, lying in bed listening but unable to watch the screen, at least for the first go around. (I’ve often done so… and yes I usually doze off, but hey—I have my priorities straight)

There is an old behaviourist slogan: Reinforce a competing activity… To me this means that, as regards the activity of drinking from a raging data stream, I focus first on what activity do I like? …Creating a poem? Practising piano? Reading the minutes from Congress? After I do so, any information flow trickles between the stepping stones of my life.

I like to keep a backlog of things I want to consume on my iPod. Audio content is magical in that you can do other things, like mowing the lawn, going for a walk, making dinner, while listening.

What I’d like to find is an easy youtube to “podcast” tool, that with just a click or two can add the audio track from any video to my iPod. Then it’s just another item in my queue that I’ll listen to eventually, without having to worry about it again.

“Who reads books any more” .. hell – I do! I read more books than ever thanks to the simplicity and ever available nature of the ebook.

Sorry I couldn’t listen to the talk after he made that statement in his opening, doesn’t he see that life today is a book reader’s paradise.

I’m off to read right now in fact!

Well Caroline, lately in my own essay blog I’ve been quoting the last half of a paragraph by Neal Stephenson in Some Remarks. (p 270)

“…Books, though, and the thoughts that go through the heads of their readers, are too long and complex to work on the screen—be it a talk show, a PowerPoint presentation, or a web page. Bookish people sense this. They don’t object to it. They don’t favor electronic media anyway. So why should they make a fuss if those media Photoshop them out of the national scene? They know how to find each other and to have the long conversations that nourish their bookish souls.”

Perhaps I should add that he writes for WIRED magazine.

I’m just so excited that something I have felt like “a minority of one” about someone credible has finally said aloud.

Hey Scot. FANTASTIC ARTICLE!! So much truth and such a refreshing perspective, just a quick one though… Did you notice 2 minor grammatical errors in the post? May be worth a re:read. Coz looks like this post’s going viral.;)

James Preston

Durban, South Africa

There is a slim volume written by a serious-minded philosophy professor that examines the role of bullshit in social fabric. It is insightful and I recommend it for anyone who ponders rhetoric, persuasion, and the public spread and clash of ideas: On Bullshit by Harry G. Frankfurt.

I wrote about the myth of information overload several years ago and agree with what you are saying here… For those interested, here is my article for Database Trends & Applications on the topic of information overload –> http://www.craigsmullins.com/dbta_102.html