Why The Right Change Often Feels Wrong

On Tuesdays I write about the top voted question on Ask Berkun (see the lovely archive). This week’s question came from J.R. [via email]:

What is a favorite theory that you wish more people understood?

A favorite theory I wish was more well known is the Satir Change Model. It’s popular in some circles, but often when I mention it in talks at events few have seen it before. Virginia Satir was a family therapist who studied how families behave, and in particular, how they respond to change. Her ideas have been successfully applied to organizations and groups of people.

We like to believe change and progress are predictable, especially if we’re applying an idea we’ve used before or that is widely accepted. But according to her research (based on family behavior), and her model, even when we’re making the right change, at the right time, confusion and fear are likely.

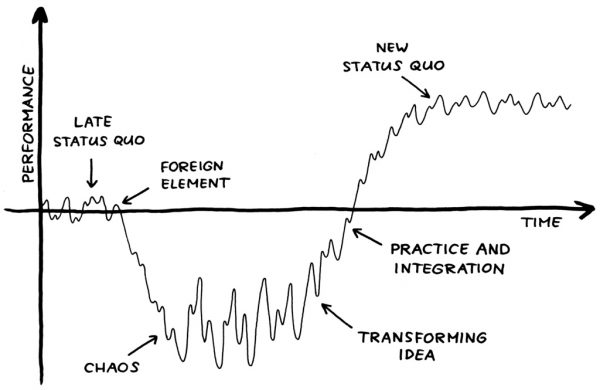

The Satir Change Model is simple and has 5 parts (image by Jurgen Appello):

- Late Status Quo – this is the present, where things are stable, at least in the sense that they’ve been the same way for some time.

- Foreign element – This is Satir’s term for any change that is introduced, which could be something deliberate (a new healthy diet) or something surprising (new neighbors move in next door). It could be a new idea, process, team member or anything. Often people resist foreign elements, even if they come with the promise of solving a problem. People often prefer to keep doing what they have been doing (status quo), even if there are things they don’t like about the status quo, especially if they don’t have much trust in their leader or their coworkers.

- Chaos – (IMO this is the central idea of the model). Even if you are doing everything right, and the change is the right one, volatility will rise for a time. Average performance will drop as people experiment with adjustments to incorporate the new idea. Hidden assumptions, and emotions, will be revealed, which can be painful at first. A new idea may require new conversations, redistribution of responsibilities and more. What makes this phase challenging is it’s hard to predict how long it will take or if the path is the right one (e.g. “do we need to keep going, or is this direction a mistake?”)

- Transforming Idea – The job of a leader is to help a team work through the chaos phase until they reach clarity. This is challenging as each person might require different coaching, advice, support or training to adopt the new idea. And the team as a whole may need to reform, with different roles and responsibilities. Someone with leadership skills might correctly identify a new direction, but it takes someone with people management skills to help them through the transitions that the new direction demands.

- Practice and Integration – Once the new idea is understood and adopted, finally the expected gains can be seen and progress becomes predictable. And eventually stabilizes again as the new status quo.

The model isn’t predictive. It doesn’t tell you how much chaos a particular idea will generate, if any at all. It can’t tell you how long it will take before you find the “transforming idea”. It also can’t tell you whether the new idea you’re introducing is the right or wrong one (e.g. the chaos will never end, or performance will never recover). It’s simply a useful framework for thinking about the psychological patterns likely to arise when something changes.

Inexperienced people often confuse the chaos phase as a failure in their choice. And if they quit early, assuming “chaos” means they made a mistake, and revert back to the old ways of doing things, they likely will never have the confidence to try something that bold again. They now confuse the chaos phase with failure. This is a kind of self inflicted learned helplessness, where the necessary cost to improve and grow is now too psychologically expensive. People and organizations can become paralyzed here, as they’ve become extremely resistant to any threat of a “foreign element”, even though that’s exactly what’s needed to grow.

Some foolish people dismiss Satir’s work based on the question what do families have to do with workplaces or individual adult choices? But workplaces are based on relationships, and we learn our models for how to relate to other people from… our families! Your favorite, and least favorite, coworkers learned many of their patterns of behavior from their early relationship with their parents and siblings. How we define trust, love, collaboration, friendship and teamwork all come from our experience with the first and primary tribe in our lives.

Anuradha Gajanayaka compares the Satir model to Kanter’s Law, which states that “Everything looks like a failure in the middle.” She suggested that we “Recognize the struggle of middles, give it some time, and a successful end could be in sight.“

And that is a key takeaway from the Satir model. Even if you’re doing everything right in your life, or as a leader, when you try to change something be prepared for surprises. Plan time for “chaos” in response to the change, where it’s normal for performance to drop and for experimentation to happen until the new idea is understood, incorporated and refined.

I haven’t looked into Satir as much as I might, (and I’m sorry about that) but I suspect she is comparable to Sigmund Freud: They both had no one else’s work to build on, they both had to come up with brilliant original things on their own.

The rest of us are pygmies standing on the shoulders of giants.

More from Satir:

Here’s one I could give to my junior manager to help him be more effective for our business:

Autobiography in 5 Short Chapters

I

I walk down the street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk

I fall in.

I am lost … I am helpless.

It isn’t my fault.

It takes me forever to find a way out.

II

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I pretend I don’t see it.

I fall in again.

I can’t believe I am in the same place

but, it isn’t my fault.

It still takes a long time to get out.

III

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I see it is there.

I still fall in … it’s a habit.

my eyes are open

I know where I am.

It is my fault.

I get out immediately.

IV

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I walk around it.

V

I walk down another street.

I love that poem and hadn’t seen it before. Thanks for sharing it here.

I love that poem, too, and I have seen it before .. and since the attribution was not clear to me in the original comment, I wanted to clarify that I believe its author is Portia Nelson.

Good catch Joe – thanks.

Goodreads has the poem referenced to her book as well.

Great timing on this post, Scott. I really needed it. I’m reminded of the saying (mis-)attributed to Winston Churchill: “If you’re going through hell, keep going.” There’s a time to push through and get to the stability on the other side and a time to cut bait and give up on a change that isn’t going to work. Telling the difference between the two is a difficult skill.

Good quote – and QI confirms it’s not Churchill.

The rub of course is you can’t be sure that you’re on the right path – you could keep going and still not succeed! Yay uncertainty!