This is an excerpt from Making Things Happen, the classic bestselling book on leading project teams, decision making and everything any leader of a project should know.

———————————-

One myth of project management is certain people have an innate ability to do it well, and others do not. Whenever this myth came up in conversation with other managers, I asked for an explanation —how to recognize it, categorize it, and, if possible, develop it in others. The only thing we identified—after considering many of the other topics covered in this book—is the ability to make things happen. Some people can apply skills in the combinations necessary to move projects forward, and others cannot, even if they have similar skills. The ability to make things happen is a combination of knowing how to be a catalyst in different situations, and having the courage to do so.

One myth of project management is certain people have an innate ability to do it well, and others do not. Whenever this myth came up in conversation with other managers, I asked for an explanation —how to recognize it, categorize it, and, if possible, develop it in others. The only thing we identified—after considering many of the other topics covered in this book—is the ability to make things happen. Some people can apply skills in the combinations necessary to move projects forward, and others cannot, even if they have similar skills. The ability to make things happen is a combination of knowing how to be a catalyst in different situations, and having the courage to do so.

This ability to drive is so important to some that it’s used as a litmus test in hiring project managers. Even if leaders can’t precisely define what the ability is without making at least some references to other skills, they do feel that they can sense or measure it in others. For example, an interviewer needs to ask herself the following question about the candidate: “If things were not going well on some important part of the project, would I feel confident sending this person into that room, into that discussion or debate, and believe he’d help find a way to make it better, whatever the problem was?” If after a round of interviews the answer is no, the candidate is sent home. The belief is that if he isn’t agile or flexible enough to adapt his skills and knowledge to the situations at hand, and find ways to drive things forward, then he won’t survive, much less thrive, on a typical project. This chapter is about that ability and the skills and tactics involved.

Priorities Make Things Happen

A large percentage of my time as a PM (project manager) was spent making ordered lists. An ordered list is just a column of things, put in order of importance. I’m convinced that despite all of the knowledge and skills I was expected to have and use, in total, all I really did was make ordered lists. I collected things that had to be done—requirements, features, bugs, whatever—and put them in an order of importance to the project. I spent hours and days refining and revising these lists, integrating new ideas and information, debating and discussing them with others, always making sure they were rock solid. Then, once we had that list in place, I’d drive and lead the team as hard as possible to follow things in the defined order. Sometimes, these lists involved how my own time should be spent on a given day; other times, the lists involved what entire teams of people would do over weeks or months. But the process and the effect were the same.

I invested so much time in these lists because I knew that having clear priorities was the backbone of progress. Making things happen is dependent on having a clear sense of which things are more important than others and applying that sense to every single interaction that takes place on the team. These priorities have to be reflected in every email you send, question you ask, and meeting you hold. Every programmer and tester should invest energy in the things that will most likely bring about success. Someone has to be dedicated to both figuring out what those things are and driving the team to deliver on them.

What slows progress and wastes the most time on projects is confusion about what the goals are or which things should come before which other things. Many miscommunications and missteps happen because person A assumed one priority (make it faster), and person B assumed another (make it more stable). This is true for programmers, testers, marketers, and entire teams of people. If these conflicts can be avoided, more time can be spent actually progressing toward the project goals.

This isn’t to say those debates about priorities shouldn’t happen—they should. But they should happen early as part of whatever planning process you’re using. If the same arguments keep resurfacing during development, it means people were not effectively convinced of the decision, or they have forgotten the logic and need to be reminded of why those decisions were made. Entertain debates, but start by asking if anything has changed since the plans were made to justify reconsidering the priorities. If nothing has changed (competitor behavior, new group mission, more/less resources, new major problems), stick to the decision.

If there is an ordered list posted up on the wall clarifying for everyone which things have been agreed to be more important than which other things, these arguments end quickly or never even start. Ordered lists provide everyone with a shared framework of logic to inherit their decisions from. If the goals are clear and understood, there is less need for interpretation and fewer chances for wasted effort.

So, if ever things on the team were not going well and people were having trouble focusing on the important things, I knew it was my fault: either I hadn’t ordered things properly, hadn’t effectively communicated those priorities, or had failed to execute and deliver on the order that we had. In such a case, working with prioritization and ordered lists meant everything.

Common ordered lists

By always working with a set order of priorities, adjustments and changes are easy to make. If, by some miracle, more time or resources are found in the schedule, it’s clear what the next most important item is to work on. By the same token, if the schedule needs to be cut, everyone knows what the next least important item is and can stop working on it. This is incredibly important because it guarantees that no matter what happens, you will have done the most important work possible and can make quick adjustments without much effort or negative morale. Also, any prioritization mistakes you make will be relative: if work item 10 turns out to have been more important than work item 9, big deal. Because the whole list was in order, you won’t have made a horrible mistake. And besides, by having such clear priorities and keeping the team focused on them, you may very well have bought the time needed to get work item 10 done after all.

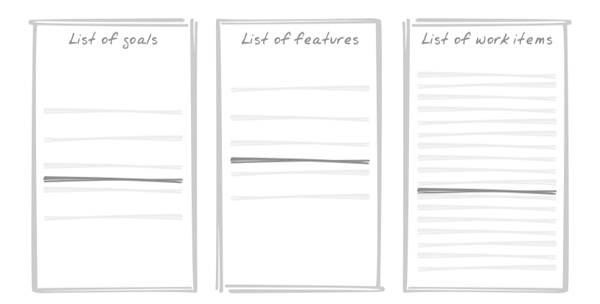

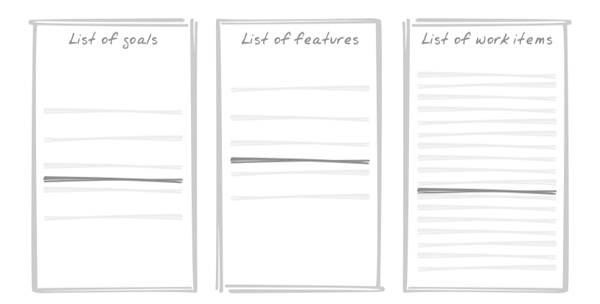

For most projects, the three most important and most formal ordered lists are used to prioritize project goals, features, and work items (see Figure 13-1). The project goals are typically part of the vision document (see Chapter 4) or are derived from it. The lists of features and work items are the output of the design process (see Chapters 5, 6, and 7). Because each of these lists inherits priorities from the preceding list, by stepping up a level to reach a point of clarity and then reapplying those priorities back down to the level in question, any disputes can begin to be resolved. Although this may not always resolve debates, it will make sure that every decision was made in the context of what’s truly important.

Figure 13-1. The three most important ordered lists, shown in order.

Other important things that might need ordered lists include bugs, customer suggestions, employee bonuses, and team budgets. They can all be managed in a similar way: put things in the order most likely to make the project or organization successful. No matter how complex the tools you use are (say, for bug tracking), never forget that all you’re doing is ordering things. If the tools or processes you use don’t help you put things in order and carry out that order, find a different tool or process. Bug triage, for example, where people get in a room and decide when a bug should be fixed (if at all), is really just a group process for making an ordered list of bugs. The bugs might be classified by group rather than on an individual bug-by-bug basis, but the purpose and effect are the same.

If you do use the three most common ordered lists, make sure that they always map to each other. Every engineering work item should map to a feature, and every feature should map to a goal. If a new work item is added, it must be matched against features and goals. This is a forcing function to prevent random features. If a VP or programmer wants to slip something extra in, she should be forced to justify it against what the project is trying to achieve: “That’s a great feature, boss, but which goal will it help us satisfy? Either we should adjust the goals and deal with the consequences, or we shouldn’t be investing energy here.” If you teach the team that it’s a rule to keep these three levels of decision making in sync, you will focus the team and prevent them from wasting time.

Priority 1 versus everything else

Typically, these ordered lists have one important line dividing them into two pieces. The top part is priority 1: things we must do and cannot possibly succeed without. The second part is everything else. Priorities 2 and 3 exist but are understood to be entirely different kinds of things from priority 1. It is very difficult to promote priority 2 items into priority 1.

This priority 1 line must be taken very seriously. You should fight hard to make that list as small and tight as possible (this applies to any goal lists in the vision document as well). An item in the priority 1 list means “We will die without this.” It does not mean things that are nice to have or that we really want to have: it gives the tightest, leanest way to meet the project goals. For example, if we were building an automobile, the only priority 1 things would be the engine, tires, transmission, brakes, steering wheel, and pedals. Priority 2 items would be the doors, windshield, air conditioning, and radio because you can get around without those things. The core functionality of the automobile exists without them; you could ship it and still call it a car.

Putting this line in place was always very difficult; there was lots of arguing and debating about which things customers could live without or which things were more important than others. This was fine. We wanted all of the debating and arguing to take place early, but then move on. As painful as it would be, when we were finished, we’d have a list that had survived the opinions and perspectives of the team. We could then go forward and execute, having refutations and supporting arguments for the list we’d made. Having sharpened it through debate and argument, we were ready for 90% of the common questions or challenges people might have later on (i.e., why we were building brakes but not air conditioning) and could quickly dispatch them: we’d heard the arguments before, and we knew why they didn’t hold up.

The challenge of prioritization is always more emotional/psychological than intellectual, despite what people say. Just like dieting to lose weight or budgeting to save money, eliminating things you want (but don’t need) requires being disciplined, committed, and focused on the important goals. Saying “stability is important” is one thing, but stack ranking it against other important things is entirely different. Many managers chicken out of this process. They hedge, delay, and deny the tough choices, and the result is that they set their projects up to fail. No tough choices means no progress. In the abstract, the word important means nothing. So, ordered lists and the declaration of a high priority 1 bar forces leaders and the entire team to make tough decisions and think clearly.

Clarity is how you make things happen on projects. Everyone shows up to work each day with a strong sense of what he is doing, why he’s doing it, and how it relates to what the others are doing. When the team asks questions about why one thing is more important than another, there are clear and logical reasons for it. Even when things change and priorities are adjusted, it’s all within the same fundamental system of ordered lists and priority designations.

Priorities are power

Have you ever been in a tough argument that you thought would never end? Perhaps half the engineers felt strongly for A, and the other half felt strongly for B. But then the smart team leader walks in, asks some questions, divides the discussion in a new way, and quickly gets everyone to agree. It’s happened to me many times. When I was younger, I chalked this up to brilliance: somehow that manager or lead programmer was just smarter than the rest of the people in the room, and saw things that we didn’t. But as I paid more attention, and on occasion even asked them afterward how they did it, I realized it was about having rock-solid priorities. They had an ordered list in their heads and were able to get other people to frame the discussion around it. Good priorities are power. They eliminate secondary variables from the discussion, making it possible to focus and resolve issues.

If you have priorities in place, you can always ask questions in any discussion that reframe the argument around a more useful primary consideration. This refreshes everyone’s sense of what success is, visibly dividing the universe into two piles: things that are important and things that are nice, but not important. Here are some sample questions:

- What problem are we trying to solve?

- If there are multiple problems, which one is most important?

- How does this problem relate to or impact our goals?

- What is the simplest way to fix this that will allow us to meet our goals?

If nothing else, you will reset the conversation to focus on the project goals, which everyone can agree with. If a debate has gone on for hours, finding common ground is your best opportunity to moving the discussion toward a positive conclusion.

Be a prioritization machine

Whenever I talked with programmers or testers and heard about their issues or challenges, I realized that my primary value was in helping them focus. My aim was to eliminate secondary or tertiary things from their plates and to help them see a clear order of work. There are 1,000 ways to implement a particular web page design or database system to spec, but only a handful of them will really nail the objectives. Knowing this, I encouraged programmers to seek me out if they ever faced a decision where they were not sure which investment of time to make next.

But instead of micromanaging them (“Do this. No do that. No, do it this way. Are you done yet? How about now?”), I just made them understand that I was there to help them prioritize when they needed it. Because they didn’t have the project-wide perspective I did, my value was in helping them to see, even if just for a moment, how what they were doing fit into the entire project. When they’d spent all day debugging a module or running unit tests, they were often relieved to get some higher-level clarity, reassurance, and confidence in what they were doing. It often took only a 30-second conversation to make sure we were all still on the same page.

Whenever new information came to the project, it was my job to interpret it (alone or through discussion with others), and form it into a prioritized list of things we had to care about and things we didn’t. Often, I’d have to revise a previous list, adjusting it to respond to the new information. A VP might change her mind. A usability study might find new issues. A competitor might make an unexpected change. Those prioritizations were living, breathing things, and any changes to our direction or goals were reflected directly and immediately in them.

Because I maintained the priorities, I enabled the team to stay focused on the important things and actually make progress on them. Sometimes, I could reuse priorities defined by my superiors (vision documents, group mission statements); other times, I had to invent my own from scratch in response to ambiguity or unforeseen situations. But more than anything else, I was a prioritization machine. If there is ever a statue made in honor of good project managers, I suspect the inscription would say “Bring me your randomized, your righteously confused, your sarcastic and bitter masses of programmers yearning for clarity.”

Things Happen When You Say No

One side effect of having priorities is how often you have to say no. It’s one of the smallest words in the English language, yet many people have trouble saying it. The problem is that if you can’t say no, you can’t have priorities. The universe is a large place, but your priority 1 list should be very small. Therefore, most of what people in the world (or on your team) might think are great ideas will end up not matching the goals of the project. It doesn’t mean their ideas are bad; it just means their ideas won’t contribute to this particular project. So, a fundamental law of the PM universe is this: if you can’t say no, you can’t manage a project.

Saying no starts at the top of an organization. The most senior people on a project will determine whether people can actually say no to requests. No matter what the priorities say, if the lead developer or manager continually says yes to things that don’t jive with the priorities, others will follow. Programmers will work on pet features. PMs will add (hidden) requirements. Even if these individual choices are good, because the team is no longer following the same rules, nor working toward the same priorities, conflicts will occur. Sometimes, it will be disagreements between programmers, but more often, the result will be disjointed final designs. Stability, performance, and usability will all suffer. Without the focus of priorities, it’s hard to get a team to coordinate on making the same thing. The best leaders and team managers know that they have to lead the way in saying no to things that are out of scope, setting the bar for the entire team.

When you do say no, and make it stick, the project gains momentum. Eliminating tasks from people’s plates gives them more energy and motivation to focus and work hard on what they need to do. The number of meetings and random discussions will drop and efficiency will climb. Momentum will build around saying no: others will start doing it in their own spheres of influence. In fact, I’ve asked team members to do this. I’d say, “If you ever feel you’re being asked to do something that doesn’t jive with our priorities, say no. Or tell them that I said no, and they need to talk to me. And don’t waste your time arguing with them if they complain—point them my way.” I didn’t want them wasting their time debating priorities with people because it was my expertise, not theirs. Even if they never faced these situations, I succeeded in expressing how serious the priorities were and how willing I was to work to defend them.

Master the many ways to say no

Sometimes, you will need to say no in direct response to a feature request. Other times, you’ll need to interject yourself into a conversation or meeting, identify the conflict with priorities you’ve overheard, and effectively say no to whatever was being discussed. To prepare yourself for this, you need to know all of the different flavors that the word no comes in:

- No, this doesn’t fit our priorities. If it is early in the project, you should make the argument for why the current priorities are good, but hear people out on why other priorities might make more sense. They might have good ideas or need clarity on the goals. But do force the discussion to be relative to the project priorities, and not the abstract value of a feature or bug fix request. If it is late in the project, you can tell them they missed the boat. Even if the priorities suck, they’re not going to change on the basis of one feature idea. The later you are, the more severe the strategy failure needs to be to justify goal adjustments.

- No, only if we have time. If you keep your priorities lean, there will always be many very good ideas that didn’t make the cut. Express this as a relative decision: the idea in question might be good, but not good enough relative to the other work and the project priorities. If the item is on the priority 2 list, convey that it’s possible it will be done, but that no one should bet the farm assuming it will happen.

- No, only if you make <insert impossible thing here> happen. Sometimes, you can redirect a request back onto the person who made it. If your VP asks you to add support for a new feature, tell him you can do it only if he cuts one of his other current priority 1 requests. This shifts the point of contention away from you, and toward a tangible, though probably unattainable, situation. This can also be done for political or approval issues: “If you can convince Sally that this is a good idea, I’ll consider it.” However, this can backfire. (What if he does convince Sally? Or worse, realizes you’re sending him on a wild goose chase?)

- No. Next release. Assuming you are working on a web site or software project that will have more updates, offer to reconsider the request for the next release. This should probably happen anyway for all priority 2 items. This is often called postponement or punting.

- No. Never. Ever. Really. Some requests are so fundamentally out of line with the long-term goals that the hammer has to come down. Cut the cord now and save yourself the time of answering the same request again later. Sometimes it’s worth the effort to explain why (so that they’ll be more informed next time). Example: “No, Fred. The web site search engine will never support the Esperanto language. Never. Ever.”

Keeping It Real

Some teams have a better sense of reality than others. You can find many stories of project teams that shipped their product months or years late, or came in millions of dollars over budget (see Robert Glass’ Software Runaways, Prentice Hall, 1997). Little by little, teams believe in tiny lies or misrepresentations of the truth about what’s going on, and slide into dangerous and unproductive places. As a rule, the further a team gets from reality, the harder it is to make good things happen. Team leaders must play the role of keeping their team honest (in the sense that the team can lose touch with reality, not that they deliberately lie), reminding people when they are making up answers, ignoring problematic situations, or focusing on the wrong priorities.

I remember a meeting I was in years ago with a small product team. They were building something that they wanted my team to use, and the presentation focused on the new features and technologies their product would have. Sitting near the back of the room, I felt increasingly uncomfortable with the presentation. None of the tough issues was being addressed or even mentioned. Then I realized the real problem: by not addressing the important issues, they were wasting everyone’s time.

I looked around the room and realized part of the problem: I was the only lead from my organization in attendance. Normally, I’d have expected another PM or lead programmer to ask tough questions already. But with the faces in the room, I didn’t know if anyone else was comfortable making waves when necessary. A thousand questions came to mind, and I quickly raised my hand, unleashing a series of simple questions, one after another. “What is your schedule? When can you get working code to us? Who are your other customers, and how will you prioritize their requests against ours? Why is it in our interest to make ourselves dependent on you and your team?” Their jaws dropped. They were entirely unprepared.

It was clear they had not considered these questions before. Worse, they did not expect to have to answer them for potential clients. I politely explained that they were not ready for this meeting. I apologized if my expectations were not made clear when the meeting was arranged (I thought they were). I told them that without those answers, this meeting was a waste of everyone’s time, including theirs. I suggested we postpone the rest of the meeting until they had answers for these simple questions. They sheepishly agreed, and the meeting ended.

In PM parlance, what I did in this story was call bull*. This is in reference to the card game Bull*, where you win if you get rid of all the cards in your hand. In each turn of the game, a player states which cards he’s playing as he places them face down into a pile. He is not obligated to tell the truth. So, if at any time another player thinks the first player is lying, she can “call bull*” and force the first player to show his cards. If the accuser is right, the first player takes all of the cards in the pile (a major setback). However, if the accuser is wrong, she takes the pile.

Calling bull* makes things happen. If people expect you will ask them tough questions, and not hesitate to push them hard until you get answers, they will prepare for them before they meet with you. They will not waste your or your team’s time. Remember that all kinds of deception, including self-deception, work against projects. The sooner the truth comes to light, the sooner you can do something about it. Because most people avoid conflict and prefer to pretend things are OK (even when there is evidence they are not), someone has to push to get the truth out. The more you can keep the truth out in the open, the more your team can stay low to the ground, moving at high speed.

The challenge with questioning others is that it can run against the culture of an individual or organization. Some cultures see questioning as an insult or a lack of trust. They may see attempts to keep things honest as personal attacks, instead of as genuine inquiries into the truth. You may need to approach these situations more formally than I did in the story. Make a list of questions you expect people to answer, and provide it to them before meetings. Or, create a list of questions that anyone in the organization is free to ask anyone at any time (including VPs and PMs), and post it on the wall in a conference room. If you make it public knowledge from day one that bull* will be called at any time, you can make it part of the culture without insulting anyone. However, leaders still have the burden of actually calling bull* from time to time, demonstrating for the team that cutting quickly to the truth can be done.

Know the Critical Path

In project management terminology, the critical path is the shortest sequence of work that can complete the project. In critical path analysis, a diagram or flowchart is made of all work items, showing which items are dependent on which others. If done properly, this diagram shows where the bottlenecks will be. For example, if features A, B, and C can’t be completed until D is done, then D is on the critical path for that part of the project. This is important because if D is delayed or done poorly, it will seriously impact the completion of work items A, B, and C. It’s important then for a project manager to be able to plan and prioritize the critical path. Sometimes, a relatively unimportant component on its own can be the critical dependency that prevents true priority 1 work from being completed. Without doing critical path analysis, you might never recognize this until it is too late.

From a higher-level perspective, there is a critical path to all situations. They don’t need to be diagrammed or measured to the same level of detail, but the thought processes in assessing many PM situations are similar: look at the problem as a series of links, and see where the bottlenecks or critical points are. Which decisions or actions are dependent on which other decisions or actions? Then consider if enough attention is being paid to them, or if the real issue isn’t the one currently being discussed. You dramatically accelerate a team by putting its attention directly on the elements, factors, and decisions that are central to progress.

Always have a sense for the critical path of:

- The project’s engineering work (as described briefly earlier)

- The project’s high-level decision-making process (who is slowing the team down?)

- The team’s processes for building code or triaging bugs (are there needless forms, meetings, or approvals?)

- The production process of propping content to the Web or intranet

- Any meeting, situation, or process that impacts project goals

Making things happen effectively requires a strong sense of critical paths. Anytime you walk into a room, read an email, or get involved in a decision, you must think through what the critical paths are. Is this really the core issue? Will this discussion or line of thinking resolve it? Focus your energy (or the room’s energy) on addressing those considerations first and evaluating what needs to be done to ensure those critical paths are made shorter, or resourced sufficiently, to prevent delays. If you can nail the critical path, less-critical issues will more easily fall into place.

For some organizations, the fastest way to improve the (non-engineering) critical path is to distribute authority across the team. Instead of requiring consensus, let individuals make decisions and use their own judgment as to when consensus is needed. Do the same thing for approvals, documentation, forms, or other possible bureaucratic overhead (see Chapter 10). Often the best way of improving critical paths in organizations is to remove processes and shift authority down and across a team, instead of creating new processes or hierarchies.

Be Relentless

“The world responds to action, and not much else.”

—Scott Adams

Many smart people can recognize when there is a problem, but few are willing to expend the energy necessary to find a solution, and then summon the courage to do it. There are always easier ways: give up, accept a partial solution, procrastinate until it goes away (fingers crossed), or blame others. The harder way is to take the problem head-on and resist giving in to conclusions that don’t allow for satisfaction of the goals. Successful project managers simply do not give up easily. If something is important to the project, they will act aggressively—using any means necessary—to find an answer or solve the problem. This might mean reorganizing a dysfunctional team, getting a difficult room of people to agree on goals, finding answers to questions, or settling disagreements between people.

Sometimes, this means asking people to do things they don’t like doing, or raising questions they don’t want to answer. Without someone forcing those things to happen, the easier way out will tend to be chosen for you. Many projects consist of people with specialized roles who are unlikely to take responsibility for things that are beyond their limited scope (or that fall between the cracks of their role and someone else’s). Perhaps more problematic is that most of us avoid conflict. It’s often the PM who has to question people, challenge assumptions, and seek the truth, regardless of how uncomfortable it might make others (although the goal is to do this in a way that makes them as comfortable as possible). PMs have to be willing to do these things when necessary.

Many times situations that initially seem untenable or intractable crumble underneath the psychological effort of a tenacious project manager. A classic story about this attitude is the Apollo 13 mission. In his book Failure Is Not an Option (Berkeley Publishing, 2001), Gene Kranz describes the effort that went into fixing the life-support system on the damaged spacecraft. It was one of the hardest engineering challenges the team faced, and there were grave doubts among those with the most expertise that even a partial solution was possible. Kranz took the position that not only would they find a way, they would do so in the limited time allotted. He refused to accept any easy way out, and he pushed his team to explore alternatives, resolving their disputes and focusing their energy. All three versions of the story, the film Apollo 13, Kranz’s book, and Lost Moon (Pocket, 1995) by Jim Lovell (the mission captain) and Jeffrey Kluger, provide fascinating accounts of one of the greatest project management and problem-solving stories in history.

Effective PMs simply consider more alternatives before giving up than other people do. They question the assumptions that were left unchallenged by others, because they came from either a VP people were afraid of or a source of superior expertise that no one felt the need to challenge. The question “How do you know what you know?” is the simplest way to clarify what is assumed and what is real, yet many people are afraid, or forget, to ask it. Being relentless means believing that 99% of the time there is a solution to the problem (including, in some cases, changing the definition of the problem), and that if it can’t be found with the information at hand, then deeper and more probing questions need to be asked, no matter who has to be challenged. The success of the project has to come first.

In my years in the Windows division at Microsoft, I worked for Hillel Cooperman, perhaps the most passionate and dedicated manager I’ve ever had. I remember once coming into his office with a dilemma. My team was stuck on a complicated problem involving both engineering and political issues. We needed another organization to do important work for us, which they were unwilling to do. I had brainstormed with everyone involved, I had solicited opinions from other senior people, but I was still stuck. There didn’t seem to be a reasonable solution, yet this was something critical to the project, and I knew giving in would be unacceptable. After explaining my situation, the conversation went something like this: “What haven’t you tried yet?” I made the mistake of answering, “I’ve tried everything.” He just laughed at me. “Everything? How could you possibly have tried everything? If you’ve tried everything, you’d have found a choice you feel comfortable with, which apparently you haven’t yet.” We found this funny because we both knew exactly where the conversation was going.

He then asked if I wanted some suggestions. Of course I said yes. We riffed for a few minutes, back and forth, and came up with a new list of things to consider. “Who haven’t you called on the phone? Email isn’t good for this kind of thing. And of all the people on the other side—those who disagree with you—who is most receptive to you? How hard have you sold them on what you want? Should I get involved and work from above you? Would that help? What about our VP? How hard have you pushed engineering to find a workaround? A little? A lot? As hard as possible? Did you offer to buy them drinks? Dinner? Did you talk to them one-on-one, or in a group? Keep going, keep going, keep going. You will find a way. I trust you, and I know you will solve this. Keep going.”

He did two things for me: he reminded me that not only did I have alternatives, but also that it was still my authority to make the decision. As tired as I was, I left his office convinced there were more paths to explore and that it was my job to do so. My ownership of the issue, which he’d reconfirmed, helped motivate me to be relentless. The solution was lurking inside one of them, and I just had to find it. Like the dozens of other issues I was managing at the same time, I eventually found a solution (there was an engineering workaround), but only because I hunted for it: it was not going to come and find me.

Among other lessons, I learned from Hillel that diligence wins battles. If you make it clear that you are dead serious and will fight to the end about a particular issue, you force more possibilities to arise. People will question their assumptions if you hold on to yours long enough. You push people to consider things they haven’t considered, and often that’s where the answer lies. Even in disagreements or negotiations, if you know you’re right, and keep pushing hard, people will often give in. Sometimes, they’ll give in just to get you to leave them alone. Being pushy, provided you’re not offensive, can be an effective technique all on its own.

Being relentless is fundamental to making things happen. There are so many different ways for projects to slide into failure that unless there is at least one emotional force behind the project—pushing it forward, seeking out alternatives, believing there is always a way out of every problem and trap—the project is unlikely to succeed. Good PMs are that force. They are compelled to keep moving forward, always on the lookout for something that can be improved in a faster or smarter way. They seek out chaos and convert it into clarity. As skeptical as project managers need to be, they are simultaneously optimistic that all problems can be solved if enough intensity and focus are applied. For reasons they themselves cannot fully explain, PMs continually hold a torch up against ambiguity and doubt, and refuse to quit until every possible alternative has been explored. They believe that good thinking wins, and that it takes work to find good thoughts.

Be Savvy

But being relentless doesn’t mean you have to knock on every door, chase people down the hallway, or stay at work until you pass out at your desk. Sheer quantity of effort can be noble and good, but always look for ways to work smart rather than just hard. Be relentless in spirit, but clever and savvy in action. Just because you refuse to give up doesn’t mean you have to suffer through mindless, stupid, or frustrating activities (although sometimes they’re unavoidable). Look for smart ways around a problem or faster ways to resolve them. Make effective use of the people around you instead of assuming you have to do everything yourself. But most importantly, be perceptive of what’s going on around you, with individuals and with teams.

A fundamental mistake many PMs make is to forget to assess who they are working with and adjust their approach accordingly. Navy Seals and Army rangers are trained to carry out missions on many different kinds of terrain: deserts, swamps, jungles, tundra. Without this training, their effectiveness would be limited: they’d struggle to survive on unfamiliar terrain because their skills wouldn’t work (imagine a solider in green and olive camouflage, trying to hide on a snow-covered field). The first lesson they learn is how to evaluate their environment and consider what tactics and strategies from their skill set will work for where they are. The same is true for PMs. Instead of geographic environments, PMs must pay attention to the different social, political, and organizational environments they are in, and use the right approaches for where they are.

Being savvy and environment-aware is most important in the following situations:

- Motivating and inspiring people

- Organizing teams and planning for action

- Settling arguments or breaking deadlocks

- Negotiating with other organizations or cultures

- Making arguments for resources

- Persuading anyone of anything

- Managing reports (personnel)

Here’s the savvy PM’s rough guide to evaluating an environment. These questions apply to an individual you might be working with or to the larger team or group:

- What communication styles are being used? Direct or indirect? Are people openly communicative, or are they reserved? Are there commonly accepted ways to make certain kinds of points? Are people generally effective in using email? Meetings? Are decisions made openly or behind closed doors? Match your approaches to the ones that will be effective with whomever you’re talking to.

- How broad or narrow is the group’s sense of humor? What topics are forbidden to laugh at or question? How are delicate/difficult/contentious subjects or decisions handled by others?

- Are arguments won based on data? Logical argument through debate? Adherence to the project goals? Who yells the loudest? Who has the brownest nose? Consider making arguments that use the style, format, or tone most palatable to your audience, whether it’s a lone tester down the hall or a room full of executives.

- Who is effective at doing <insert thing you are trying to do here>, and what can I emulate or learn from them? Pay attention to what works. Who are the stars? Who gets the most respect? How are they thriving? Who is failing here? Why are they failing?

- In terms of actual behavior, what values are most important to this person or group? Intelligence? Courage? Speed? Clarity? Patience? Obedience? What behaviors are least valued or are deplored? Programmers and managers might have very different values. Know what the other guy values before you try to convince him of something.

- What is the organizational culture? Every university, corporation, or team has a different set of values built into the culture. If you don’t think your organization has one, you’ve been there too long and can’t see it anymore (or maybe you never saw it at all). Some organizations value loyalty and respect above intelligence and individuality. Others focus on work ethic and commitment.

Depending on the answers to these questions, a PM should make adjustments to how she does her work. Every time you enter another person’s office, or another meeting, there should always be some adjustments made. Like a Marine, assess the environment and then judge the best route to get to the project goals. Avoid taking the hard road if there is a smarter way to get where you need to go.

Guerilla tactics

Being savvy means you are looking for, and willing to take, the smarter route. The following list contains tactics that I’ve used successfully or have been successfully used on me. While your mileage may vary with them, I’m sure this list will get you thinking of other savvy ways to accomplish what needs to be done to meet your goals. Some of these have risks, which I’ll note, and must be applied carefully. Even if you choose never to use these yourself, by being aware of them, you will be savvier about what’s going on around you.

- Go to the source. Don’t dillydally with people’s secondhand interpretations of what someone said, and don’t depend on written reports or emails for complex information. Find the actual person and talk to him directly. You can’t get new questions answered by reading reports or emails, and often people will tell you important things that were inappropriate for written communication. Going to the source is always more reliable and valuable than the alternatives, and it’s worth the effort required. For example, if two programmers are arguing about what a third programmer said, get that third programmer in the room or on the phone. Always cut to the chase and push others to do the same.

- Switch communication modes. If communication isn’t working, switch the mode. Instead of email, call them on the phone. Instead of a phone call, drop by their office. Everyone is more comfortable in some mediums than others. (Generally, face to face, in front of a whiteboard, trumps everything. Get people in a room with a whiteboard if the email thread on some issue gets out of control.) Don’t let the limitations of a particular technology stop you. Sometimes, switching modes gets you a different response, even if your request is the same, because people are more receptive to one mode over another. For anything consequential, it’s worth the money and time to get on a plane, or drive to their office, if it improves the communication dynamic between you and an important co-worker.

- Get people alone. When you talk to someone privately, her disposition toward you is different than when you talk to her in a large group. In a meeting, important people have to craft what they say to be appropriate for all of the ears in the room. Sometimes, you’ll hear radically different things depending on who is in earshot. If you want a frank and honest opinion, or an in-depth intense conversation, you need to get people alone. Also, consider people of influence: if Jim trusts Beth’s opinion, and you want to convince Jim, if you can convince Beth first, bring her along. Don’t ambush anyone, but don’t shy away from lining things up to make progress happen.

- Hunt people down. If something is urgent and you are not getting the response time you need, carve out time on your schedule to stake out the person’s office or cubicle. I’ve done this many times. If he wasn’t answering my phone calls or emails, he’d soon come back from a meeting and find me sitting by his door. He’d usually be caught so off guard that I’d have a negotiating advantage. Don’t be afraid to go after people if you need something from them. Find them in the coffee room. Look for them in the cafe at lunchtime. Ask their secretary what meetings they are in and wait outside. Be polite, but hunt and get what you need. (However, please do not cross over into their personal lives. If you hunt information well, you shouldn’t ever even need to cross this particular line.)

- Hide. If you are behind on work and need blocks of time to get caught up, become invisible. On occasion, I’ve staked out a conference room (in a neighboring building) and told only the people who really might need me where I was. I caught up on email, specs, employee evaluations, or anything important that wasn’t getting done, without being interrupted. For smaller orgs, working from home or a coffee shop can have the same effect (wireless makes this easy these days). I always encouraged my reports to do this whenever they felt it necessary. Uninterrupted time can be hard for PMs to find, so if you can’t find it, you have to make it.

- Get advice. Don’t fly solo without a map unless you have to. In a given situation, consider who involved thinks most highly of you, or who may have useful advice for how you can get what you need. Make use of any expertise or experience you have access to through others. Pull them aside and ask them for it. This can be about a person, a decision, a plan, anything. “Hey Bob, I’d like your advice on this budget. Do you have a few minutes?” Or, “Jane, I’m trying to work with Sam on this issue. Any advice on the best way to convince him to cut this feature?” For many people, simply asking their advice will score you credibility points: it’s an act of respect to ask for someone’s opinion.

- Call in favors, beg, and bribe. Make use of the credibility or generosity you’ve developed a reputation for. If you need an engineer to do extra work for you, either because you missed something or a late requirement came in, ask her to do you a favor. Go outside the boundaries of the strict working relationship, and ask. Offer to buy her dinner ($20 is often well worth whatever the favor is), or tell her that you owe her one (and do hold yourself to this). The worst thing that can happen is that she’ll say no. The more favors you’ve done for others, the more chips you’ll have to bank on. Also, consider working three-way trades (e.g., in the game Settlers of Cattan) if you know of something she wants that you can get from someone else. It’s not unethical to offer people things that will convince them to help with work that needs to be done.

- Play people off each other. This doesn’t have to be evil—if you’re very careful. If Sam gives you a work estimate of 10 days, which you think is bogus, go and ask Bob. If Bob says something less than 10 days, go back to Sam, with Bob. A conversation will immediately ensue about what the work estimate really should be. If you do this once, no engineer will ever give you bogus estimates again (you’ve called bull*). However, depending on Sam’s personality, this may cost you relationship points with him, so do it as tactfully as possible, and only when necessary. Good lead programmers should be calling estimate bluffs on their own, but if they don’t, it’s up to you.

- Buy people coffee and tasty things. This sounds stupid, but I’ve found that people I’ve argued with for days on end are somehow more receptive over a nice cup of coffee at a local coffee shop. Change the dynamic of the relationship: no matter how much you like or don’t like the person, make the invitation and invest the 20 seconds of effort it requires. Even if he says “No, why can’t we talk here?” you’ve lost nothing. Moving the conversation to a different location, perhaps one less formal, can help him open up to alternatives he wouldn’t consider before. Think biologically: humans are in better moods after they’ve eaten a fine meal or when they are in more pleasant surroundings. I’ve seen PMs who keep doughnuts or cookies (as well as rum and scotch) in their office. Is that an act of goodwill? Yes … but there are psychological benefits to making sure the people you are working with are well fed and associate you with good things.

Summary

- Everything can be represented in an ordered list. Most of the work of project management is correctly prioritizing things and leading the team in carrying them out.

- The three most basic ordered lists are: project goals (vision), list of features, and list of work items. They should always be in sync with each other. Each work item contributes to a feature, and each feature contributes to a goal.

- There is a bright yellow line between priority 1 work and everything else.

- Things happen when you say no. If you can’t say no, you effectively have no priorities.

- The PM has to keep the team honest and keep them close to reality.

- Knowing the critical path in engineering and team processes enables efficiency.

- You must be both relentless and savvy to make things happen.

—————————–

15 more chapters of goodness await you in Making Things Happen.

Other classic chapters include:

Other classic chapters include:

- The truth about schedules

- How to figure out what to do

- What to do when things go wrong

- How not to annoy people

- Power and Politics

- Buy the bestselling book here

At

At