In Defense of Brainstorming

Periodically popular articles arise decrying brainstorming as flawed (Jonah Lehrer’s article in the New Yorker, Groupthink: the brainstorming myth, is a popular one). Most of these articles miscast what brainstorming was designed to do, how ideas in workplaces are actually developed and what was actually observed in research studies.

Here are 4 key things often mentioned which shatter the typical headline and conclusion of these articles:

- Brainstorming is designed for idea volume, not depth or quality. The term brainstorming is loosely used today, but it’s origins by Alex Osborn had a very specific set of rules and intentions. His primary goal was to help groups create a long list of ideas in a short amount of time. The assumption was that later a smaller group would review, critique, improve, later on. Finding great ideas was never the intent. He believed most work cultures are repressive, not open to ideas, and the primary thing needed was a safe zone, where the culture could be different. He believed if the session was lead well, a positive and supportive attitude helped make a larger list of ideas. Obsorn believed critique and criticism were critical, but there should be a (limited) period of time where critique is postponed. Other methods may generate more ideas than brainstorming, or better ones, but that doesn’t mean brainstorming fails at its goals.

- The person leading an idea generation session matters. Using a technique is only as good as the person leading it. In Nemeth’s research study, cited in Lehrer’s article, there was no leader (which is often true in academic research studies on creativity, or participants are asked to be creative alone). Undergraduates were given a short list of instructions: that was the entirety of their training. Doing a “brainstorm” run by a fool, or a smart person who has no skill at it, will disappoint. This is not a scientific evaluation of a method. Its like saying “brain surgery is a sham, it doesn’t work”, based not on using trained surgeons, but instead undergraduates who were placed behind the operating table for the first time [See Isaksen & Gaulin 2005]

- Generating ideas is a small part of the process. The hard part in creative work isn’t idea generation. It’s making the hundreds of decisions needed to bring an idea to fruition as a product or thing. Brainstorming is an idea generation technique, and nothing more. No project ends when a brainstorming session ends, it’s just beginning. Lehrer assumes better idea generation guarantees better output of breakthrough ideas, but this is far from true. Many organizations have dozens of great ideas, but fail to bring any of them into active projects (too risky/scary), or to bring those active projects successfully into the market. Generating good ideas that can gain organizational support perhaps have more value in most contexts.

- Team chemistry and creative ability matters. Most creativity studies are run on teams of people who do not know each other. It’s harder to do anything well as a group with people you do not know. One critical step in a real world brainstorming session is picking who will participate (based on intelligence, group chemistry, diversity, etc ). No method can instantly make morons smart, the dull creative, or acquaintances intimate. The people in Nemeth’s research study, the one heavily referenced by Lehrer, had never met each other before and were chosen at random. A very different environment than any workplace.

- Studies often measure trivial creativity. To simplify the collection of research data, many studies use trivial kinds of creativity, like inventing product names for made up products. The focus is on being unique in an absolute context. What relationship does this have to the more complex kinds of creativity most people pursue in the real world (solving problems, finding new approaches, discovering new ways to approach a domain, etc.) new ideas for organizing work, etc.)? No one knows and these research studies often don’t mention this important distinction. An idea does not have to be unique to be a great solution to a real world problem. [Added 11/27/2020]

1. Understanding Idea Divergence vs. Convergence

Lehrer writes:

“While the instruction ‘Do not criticize; is often cited as the important instruction in brainstorming, this appears to be a counterproductive strategy. Our findings show that debate and criticism do not inhibit ideas but, rather, stimulate them relative to every other condition.”

The intention of brainstorming is not to eliminate critique, but simply to postpone it. Workplaces are notorious for killing ideas quickly with phrases like “We tried that already” or “that won’t work here” or even “that’s too crazy” (List of familiar idea killers heard regularly in workplaces). Great ideas often seem crazy or weird at first and if they are discarded or criticized before given time to breathe they’re lost before they had a chance to show their merit.

In ordinary life when people face big decisions, like where to go on vacation, it’s common to come up with a big list of ideas, only adding items for a time. And then once the list seems reasonably long, only then does critique and debate start. This is known as divergence / convergence. You explore and add (diverge) and then cull and refine (converge). Most creative people, and processes, shift back and forth between divergence (seeking, exploring, experimenting) and converging (eliminating choices, simplifying, deciding). Brainstorming and nearly all idea generation techniques are divergence acts. And need to be paired with a separate activity that converges.

Simply put, there is an assumption in most research about creativity that only a singular method is ever used. This is wrong. Most successful creative teams use a combination of methods. Sometimes people work alone, sometimes in groups. Sometimes there is a formal activity, sometimes not. Sometimes the goal is to diverge, sometimes the goal is to converge. Their effectiveness is the combination of all of these activities over the course of a project. But most research assumes there is only one event for creativity that ever happens, and seeks to find the ideal event, which is absurd. I understand the focus on a single activity simplifies research, but it also limits the application of that research.

In Osborn’s best book on the brainstorming method, Applied Imagination, he wrote on page 197:

“Although creative imagination is essential… judgement must play an even larger part.”

And he details several processes for evaluating, critiquing, and reporting on ideas. On page 200 he states:

“A list of tentative ideas [e.g. the output of a brainstorming session] should be considered solely as a springboard for future action… as a pool of ideas to be screened, evaluated and further developed before solutions can be arrived at.”

2. Reading the 2003 Brainstorming Study

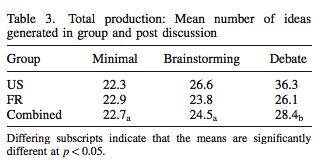

The primary thrust of Lehrer’s critique is based on a 2003 study by Nemeth (PDF), where students were divided into groups and given 3 different sets of instructions. In one group, no instruction was given (‘Minimal’). In the second group, basic brainstorming rules were given (‘Brainstorming’). In the last, brainstorming rules were given, plus students were allowed to critique each others ideas (‘Debate’). But no group was trained in how to brainstorm, nor given an example of effective brainstorming to watch.

Is the debate group brainstorming, or not? They were given the same instructions, plus one additional one (‘it’s ok to criticize’). The results do show that the group that could critique generated more ideas: but not many more. For all the participants, it was a difference of ~4 ideas. 28.4 ideas for the “debate” group and 24.5 for the “brainstorming” group. About 14%. In the U.S. this number was much higher, closer to 30%.

But these columns are mislabeled. The debate groups was given brainstorming instructions, as well as an instruction to debate. It should be labeled “Brainstorming with debate“. If the only instruction they were given was to debate, it’d be a fair comparison. But it isn’t.

3. Is Brainstorming Useless?

Lehrer’s writes:

“But if brainstorming is useless, the question still remains: What’s the best template for group creativity?”

He’s wrong. The data from Nemeth claims brainstorming (Column 2 in the table above) is more effective than giving people no advice at all, but not as effective as brainstorming where criticizing is allowed. I don’t agree with Nemeth’s conclusions, but Lehrer does, and assuming he’d read the study he’d have seen the table above which show brainstorming generated more ideas than the control group.

More importantly, he’s asking the wrong question. There is no singular best template for group creativity. When I’m hired to advise teams, the first thing I do is study the culture of the team. My advice will be based on who they are and what will work for them, not on an abstract set of principles. Just as there isn’t a best template for group morale, or teamwork, or group anything. Is there a singular best template for good writing? For being a good person? A singular template denies how divergent individuals, teams and cultures are. Nemeth’s data shows a wide disparity between French and American success at brainstorming: clearly culture does matter.

Lehrer assumes there is a universal principle that, if discovered, would make everyone more creative. This works against the very idea of creativity: which is that each person sees the world in a different way, and it’s through exploring those differences, rather than avoiding them, than new and different ideas can be found. For groups, this means each group has it’s own strengths and weaknesses, and what will help or hurt their creative output will differ. Some teams are too freewheeling, others not enough.

4. Anecdotes, Data and MIT’s mythical building 20

Lehrer goes on to discuss the legendary building 20 at MIT’s Cambridge campus. He writes:

“Building 20 and brainstorming came into being at almost exactly the same time. In the sixty years since then, if the studies are right, brainstorming has achieved nothing – or, at least, less than would have been achieved by six decades worth of brainstormers working quietly on their own. Building 20 though, ranks as one of the most creative environments of all time, a space with an almost uncanny ability to extract the best from people. Among M.I.T. people, it was referred to as the magical incubator.”

MIT is one of the greatest concentrations of brilliant people in the history of the world. The campus is filled with buildings where great things were invented. Lehrer offers no data about the number of inventions discovered in Building 20 vs. Building 19 or E15 (where the famed Media Lab resides). He mentions Building 20 “ranks as one of the most creative environments of all time”, but there is no actual ranking. If you wanted to measure the magic of building 20 scientifically, you’d perhaps replicate the building in the middle of an empty field in Kansas, and fill it with average people. Does magic happen? More magic than other kinds of buildings in the same place? Nehmer’s brainstorming studies were done with random college undergraduates who had just met. If you want to compare brainstorming to Building 20, you’d need to try to place some fair comparisons, which Lehrer does not do.

I agree environment matters, but there’s plenty of evidence great things happen independent of environment. There was nothing magical about the buildings used for the Manhattan project. Nor for the NASA engineers who worked on the Apollo 11 moon landing mission. The car garage is the prototypical silicon valley environment for innovation, and many ideas that drive our tech-sector came from garages and cubicles. How does the legend of Building 20 compare with these other buildings? What shared lessons can be learned that incorporates these diverse examples of environment? Lehrer doesn’t say. In building 20, what idea generation techniques did they use (and was brainstorming one of them?), or did they all just meet randomly in corridors? He also doesn’t say. Did they work together at blackboards? At the cafe? I’m sure they used many different methods, and the combination of those methods matters.

5. The only lessons I can derive

The best lesson I can pull from Lehrer’s mess of an article is this: creativity is personal. Building 20 was built cheaply and seen as a failure, which made it easier for motivated creatives to rearrange and redesign the environment. There were fewer rules than your typical building. They were allowed to take control over how they worked. The diversity of people forced people to hear different points of view. And the highly empowered and competitive pool of makers ensured things would ship, and not languish in bureaucracy or self-doubt.

If you want more creativity, hire people who demonstrate creativity. Do not expect to magically graft it onto people you hired for their rigid conservatism. Then give them resources and get out of their way. Let them decide what methods to use or not. If you want to know how to generate ideas in groups, go find a creative group and watch what they do. You’ll learn more from observing that experience than Lehrer’s article.

Related:

- A previous defense of Brainstorming against Marc Andresen, with supporting links.

- The Dance of The Possible, my guide to effective creative thinking.

Interesting article but you might want to revise to get Lehrer’s name right–it’s spelled three different ways throughout the article.

Jeremy

Indeed. Apologies. Fixed now.

Still two instances of Lerner and one of Leher. :)

Ok. It’s really fixed now. Thanks again.

I am certainly one of those who is apparently a brainstorming naysayer. Hell, I have a blog post (from a few years ago) titled Brainstorming is for Suckers.

I use similar phrasing in presentations on design process. But largely to get everyone’s attention. Because you may be the only person in the world who does it right. Assuming you can even do it right, and your workplace supports the environment you mentioned of following up. Everyone else was taught it in grade school the way Nemeth tested it: there are no wrong ideas, there is no moderator and sometimes not a single scribe, and then… nothing. Maybe we vote right then on the coolest idea.

But like there are stupid questions, there /are/ stupid ideas. Or at least irrelevant ones. If you have a room of smart people, I like to add constraints on them right away, at the first step. We know we’re coming up with ways to improve sales via the mobile web, so how does it do anyone any good to talk about ways to find the TV remote (I am not even exaggerating).

Like a lot of design memes, neither the I Hate Brainstorming group or the I Love Brainstorming group (mostly) have any idea why. I’d love to know, do you ever stop and say “what do you mean” when a client group says they’ll have a brainstorming session?

Be a conscious designer. Know not just the names of your tools, but why they work and how to use them.

I always ask what do you mean when people say “we’re doing a brainstorming session”. Most of the time they mean they’re going to get in a room and try to come up with ideas, without much structure, or even much thinking about what worked last time or didn’t.

Of course there are stupid ideas. But there is no reason stupid ideas have to be identified as such immediately. Sometimes a very stupid idea can be the catalyst for someone else to offer an amazing one. Free play has its place. It’s not every place, but there you go.

It’s useful to look at other fields. What rules do comedians follow when they are doing improv? Or musicians when they are jamming? You’ll find many of the concepts are similar to what at least some of Obsorn’s theory. Keeping it positive and building on other people’s ideas for a time has value.

Great post, Scott.

As someone who actively uses some of these methods (not to the exclusion of others), privately and in groups, I wholeheartedly agree with your refutations. Most people treat the word ‘brainstorming’ as they would ‘creativity’: it is applied with astonishing irresponsibility to a variety of concepts ranging from mere discussion to deep thought. And that anyone, with minimal instruction or exposure, can be plunged into this activity. Almost as if it is a primeval instinct.

Banning the word may be a good beginning.

Very interesting piece. Love your work on these topics (ESP.’myths of innovation’)

The criticism of ‘poor, badly managed brainstorming’ is valid and supported by a lot of research. Anyone who has spent time in the corporate world knows this. I am sure teams of smart, balanced, considerate creatives who know each ither can use the tool brilliantly. But not every session is like that is it? Many (by no means all) such sessions are poorly run, dominated by a few people and are based on a manic rush which does not allow ideas and thoughts to evolve.

However – well managed such sessions can be a smart. Like any tool PowerPoint, SEO, Social Media etc – there is good use. But too often the tool becomes a knee jerk reaction as the first and only thing to do.

My own preference (based on 20 years working in media and marketing industries) is to get small groups thinking about creative ideas over time. The best work I have seen is when yiu develop a great brief and give a team of 2 or 3 a few days to sketch some kdeas. That is why you have songwriting partnerships and small group collaborations. Also – the Knowledge Cafe Concept for discussion is very useful. Allowing the chance to discuss the question, explore the topic, share insights and thoughts but NOT aiming for an instant list of 50 ideas. I explore this more in my blog – http://www.andrewarmour.com

Yes, well managed brainstorming can be useful. In my view though the deeper cultural and group dynamic that needs to be nurtured is COLLABORATION and its key element – CONVERSATION. And a good creative conversation does not always need ten people, flip charts, marker pens and blue tak!

Thanks.

Regards,

Andrew Armour

http://www.benchstone.co.uk

http://www.andrewarmour.com

It has always seemed to me that the Scientific Method values tenacity very highly, and creativity hardly at all. I think this is part of why Discovery so infrequently benefits the person that did the discovering; they lack the creativity to do anything about it.

It is not all that surprising to me that a scientific study of Creativity would break the test subject in the process. It’s something that ‘those people do’, not us smart people.

Great article, Scott.

I have chaired numerous brainstorming sessions and some have been more successful than others. I completely agree that the session is the start of the ideas process and not the end. And also, that there’s no place for the dismissal or critique of ideas ‘thrown’ out. The purpose, to me, is to generate as many ideas as possible in an allotted time.

The whittling down of ideas can come after.

As you say, it’s important to have talented people participating whose opinion and ideas you respect. Obviously, there is always room for more junior members of the team who can hopefully learn from the process.

Another important aspect is to get people from diverse disciplines together, whose different skill sets can come together to create something new and startling.

If done properly, brainstorming sessions can be great for team building and having fun!

Thanks,

David.

I’d be interested to see any references you might have to scientific literature showing that brainstorming works. To the contrary, it appears overwhelmingly to show that brainstorming neither produces more ideas nor better ones. The Nemeth article was just one of the later additions to this debate.

See for example: Diehl, M., and W. Stroebe. “Productivity Loss In Brainstorming Groups: Toward the Solution of a Riddle.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53, no. 3 (1987): 497-509.

In this study, the authors list (beginning in the 1950s) 22 studies that compare brainstorming to the production of individuals. 18 of the studies show inferior idea production by the brainstorming groups and 4 show equal idea production. None shows superior idea production, and the 4 with equal idea production used groups of just two persons.

BTW, Lehrer appears to be riding the wave of Susan Cain’s new book: “Quiet, The Power of Introverts”. See her NYT article on the topic: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/15/opinion/sunday/the-rise-of-the-new-groupthink.html

So, there’s the rub. Brainstorming is the Fax Machine of creativity: a method that just won’t die despite the existence of better methods.

By the way, the issue is being debated here in Germany as well. See, http://www.teamworkblog.de (in German).

Great response to Lehrer’s article. I agree, every group works differently and brainstorming sessions might not be the best solution for everyone. I think it should go without saying that any brainstorming session needs a review & critique (i.e. constructive discussion) after it’s done and there has to be follow-up and accountability. Otherwise it really *is* a waste of time.

However, it bothers me that this discussion (which started showing up in a number of places online over the last couple of weeks) seems to be framed in an either/or discussion, dismissing brainstorming completely as a method.

Having been burned at work, I have a daydream of what to say next time.

“We have a fine proud company, but I’m not convinced we are capable of brainstorming. May I propose a constructive alternative? Suppose we just come up with the same ideas we would have normally, if we were taking our time, but instead we generate the ideas real fast and write them down for all to see, saying that all ideas are acceptable. That way we won’t get mixed up with real, classical brainstorming, and we will save time by being so fast.”

This gives the group the chance to say, “Yes, that’s what we meant to do all along” (very likely) or to explore what classical (Osborn) brainstorming is. (very unlikely)

Great article Scott!

We have been in the innovation business for 15 years now and its never been either or. Especially since it’s hard to guarantee great ideas, multiple ways of working is the only way forward (individual and group are both needed and they are just two pieces of the pie).

Brainstorming is but one of hundreds of IDEA GENERATION methods. All of the newer ones out perform BS on quantity, originality and energy. So please people, when you talk about idea generation in general stop saying the name of this tired old-timer. There has been some development in the last 60 years..:)

@andreasbreiler

@idelaboratoriet

An interesting dissenting perspective on the championing of dissent over pure positivity. In my reading of Jonah Lehrer over the years, he often plays the role of provocateur … a role I would also associate with Scott Berkun :)

Provocateurs sometimes overstate their cases – indeed, this is often what provokes responses – and it was very helpful to read this thorough response to claims made in Lehrer’s article. That said, I would like to offer a few dissenting clarifications to the dissenting clarifications offered here.

The quote attributed to Lehrer in section 1 of this article is a quote Lehrer excerpted from the Nemeth study. In section 2, I consider the omission of “brainstorming” from the label in the third column of the table from that study (which, as you point out, would more properly be labeled “brainstorming + debate”), to be acceptable within the context of the Nemeth report on the study. Finally, I don’t agree with the critique of claims regarding the creativity inspired in – and by – Building 20; I have generally found that physical spaces that afford easy redesign and reconstruction, as well as those that promote incidental conversations, to be highly conducive to creativity and collaboration.

Shifting from dissent to assent, the broader points you make about the critical importance of the individual people and processes involved in creative activities – and spaces – are well taken. I agree that the skills and motivations of the leaders and participants in generating and refining ideas are vitally important in achieving productive outcomes. I have been involved in “brainstorming” activities with [intrinsically] unmotivated participants led by unskilled facilitators – not unlike the students in Nemeth’s study – and have found the process extremely frustrating.

I suspect this lack of intrinsic motivation and skilled facilitation – during and after brainstorming – is why so many organizations fail to capitalize on creative ideas … and perhaps why some are so skeptical about “brainstorming”.

I appreciate the opportunity to reflect more deeply on practices and processes for promoting creativity offered by the contrasting opinions articulated here and in Lehrer’s article.

Thanks for the thoughtful critique Joe.

It’s great to be provocative if your provocation is grounded in fact and understanding of what it is your provoking. As Scott very aptly notes in this thoughtful commentary, Lehrer doesn’t. Lehrer slams brainstorming for not critically evaluating ideas when it has never been intended to do any such thing. He demonstrates a lack of understanding of how we move from creative to critical to constructive thinking in group process. It was a very disappointing piece from someone who knows better, and it is unfortunate that its provocative titling has garnered it significant attention.

Great article. One very important matter when brainstorming is that brainstorms need practice, the more you do, the better your at them. Also, before starting it is recommended to do a previous and short simple brainstorm, like “ideas for waking up early” or “ways of how to arrive on time to a date without a car”, these kind of exercises stimulate our brains and let us be more creative when the real brainstorm is needed.

Great article. One very important matter when brainstorming is that the process needs practice, the more you do, the better you are at them. Also, before starting it is recommended to do a previous and short simple brainstorm, like “ideas to wake up early” or “ways of how to arrive on time to a date without a car”. These kind of exercises stimulate our brains and let us be more creative when the real brainstorm is needed.

Is the Lehrer article actually an “attack on the concept of brainstorming”? His assumptions and reasoning are flawed, but I think the article is about the ‘act’ of brainstorming rather than the ‘concept’ of brainstorming.

The article is a mess and the mess starts with the title; “GROUPTHINK The brainstorming myth”.

If you search for the main idea of the piece (an actual quote that states the main idea) you only find it finally in the last paragraph; “The fatal misconception behind brainstorming is that there is a particular script we should all follow in group interactions.” If you drop the over the top word ‘fatal’, you have the author’s main idea; that there is no particular script to follow in group interactions. The author actually does support that idea with evidence, evidence which you may argue with, but with enough evidence that he actually does have a point (however flawed and assumption-filled).

In defense of Lehrer

I saw Lehrer’s article when it ran in the New Yorker and I enjoyed it quite a lot. I feel that your criticism of his _reporting_ of Nemeth’s findings is unfair though.

On your first point, “nothing matters if the room is filled with morons or strangers (or both),” the study and Lehrer’s article aren’t arguing about the quality of the ideas generated by a brainstorming session. They are concerned with the quantity, so arguing that garbage in equals garbage out isn’t relevant. As an aside, I don’t think anyone would dispute that uninformed or dim people will not generate relevant, high quality ideas.

On your second point, “brainstorming is designed for idea volume, not depth or quality,” this is in fact the precise aim of the study, to test whether brainstorming as conventionally practiced generates a greater quantity of ideas than if participants were instructed to brainstorm AND debate. I have no doubt that Osborn recommend criticizing and developing ideas after the brainstorming session (after all, what else would you do with them) but Nemeth’s findings show that debating while brainstorming produces MORE ideas. If the object of brainstorming as conventionally practiced is to produce as many ideas as possible (regardless of quality), Nemeth’s study shows it’s not as effective at generating quantity than brainstorming with debate.

To your third point, “so is brainstorming useless,” Lehrer is not referring to Nemeth’s study since he makes this statement earlier in the article than his first mention of Nemeth. In fact, he uses Nemeth’s study as the ANSWER to the question, “is brainstorming useless,” with the implication being, no it’s not, so long as you instruct people to debate. His statement “so is brainstorming useless” is referring to a different study conducted at Yale by Donald Taylor, Paul Berry and Clifford Block in 1959 called “Does Group Participation When Using Brainstorming Facilitate or Inhibit Creative Thinking?” The conclusion of their study was that people working as individuals (and then pooling their output) produced not just more unique ideas than brainstorming under Osborn’s rules, but higher quality ideas to boot (as judged by a panel of experts). It is from this study, not Nemeth’s, that Lehrer concludes that brainstorming using Osborn’s rules is useless.

On Building 20, I think Lehrer got a bit carried away. Here he’s not citing a study with control groups. He’s examining the successes that came out of a particular building and attributing it to the building design. The occupants of the building themselves apparently think the building design was a factor but the reality of it is we don’t know that for sure and it’s CERTAINLY not the only reason why so many innovations came out of one building – it was at MIT after all.

I should say that I don’t know Jonah Lehrer so I didn’t feel compelled to defend him personally. I liked his article and after reading your critique it seemed that you were confusing some things and being unfair to his article.

Regards,

Brian

I love this statement: “If you want more creativity, hire people who demonstrate creativity. Do not expect to magically graft it onto people you hired for their rigid conservatism. Then give them resources and get out of their way”

This is what current management at our office does. I came in hired for my creativity. The current director is not imaginative and is shocked when our more conservative culture doesn’t come up with anything new.

Failure of Imagination.

It took me a while to understand what this phrase really means.

Are there really ‘silly ideas’? I think the question should be, “Based on what we do (our purpose), the resources we have, and our innovation strategy (will we be first, a fast follower etc.), is this idea silly?”

To say that brainstorming is a waste of time is like saying talking is a waste of time. Too general a statement and to simplistic.

I find articles like this frustrating: They agree in substance with the thing they’re claiming to critique, but laser in on some tiny nits to claim they’re in disagreement.

Basically, what the author of this piece is claiming is that what’s promulgated throughout the creative industries as “Brainstorming” isn’t really brainstorming; that Lehrer’s critiquing a straw man.

Thing is, I can tell you from long and frustrating personal experience that it’s no straw man. I can’t even tell you how many times I’ve heard the “no criticisms” admonition, and seen crap result.

Someone on Metafilter put this well, so I’ll paraphrase him: Brainstorming, as it’s practiced in the creative industries today, is really basically a wall-reading exercise — designed to get everyone on the same team looking in the same direction and feeling like they’ve been heard before the ‘creative team’ goes off and does whatever the hell they want.

This subject has interested me for some time now and in my humble opinion there may be another thing worth considering.

As I see it there are there may be two kinds of creative people; those with what I call ‘associative creativity’ (they are really good in connecting unrelated matters and do well when exposed to a lot of ideas), and those with ‘reflective creativity’ who are good in storing things in their ‘working memory’ and reflect on it in a quiet environment.