Per Richard’s complaint, I’ve finally answered the questions mentioned back in September (hanging head in shame), when I spoke at Microsoft Research’s speaker series.

These were some of the questions I was asked during Q&A, with fresh and extended answers:

Q: How do you rationalize your statement that there is no single method for innovation, with your advice for managers (delegate) at the end of your talk?

The advice I gave (delegate, take risks, reward initiative) is the best basic advice for the most common problems I see in my travels. The three most common failings in managers that say “I want my team to innovate” are failing to trust their teams (delegate), failing to make big bets (take risks), and penalizing people for following their ideas into controversial territory.

This isn’t a magic recipe that works 100% of the time, but if I’m talking to a crowd of 200 people and know nothing about their individual circumstances, this is the first advice I offer. Its’ simple stuff, but still rare even when the I-word is thrown down as a goal.

Q: In your Luddite example you pointed out how hard it is to make change happen. Any advice for innovators on working around this challenge?

1. Pick your manager carefully. Your direct boss has more influence on your ability to take risks than anyone else in the company. I’d rather work on a boring, v12 product with a great aggressive manager who wants change to happen, than be on super-duper cutting edge big budget team, with a scared, conservative, Paxil addicted manager who says No to everything.

2. Don’t call what you’re doing change. Call it satisfying customers. Call it making money. Find some other attribute that your idea will provide the company and focus on talking about that instead. Don’t say “This is a huge revolution in blah blah blah.” Instead pitch something like “This plan will eliminate our top 5 customer complaints and improve sales by 10%”. Make a non-change centric argument. It’s not hard. Fish through the project and division goals for a good angle to pitch your ideas.

3. Find allies. Study any revolution and you’ll find cabals, coalitions, and partnerships. Who are your partners for change? You have to weigh the size of your ideas against the size of your political power. Have big ideas? Get more power. Can’t get more power? Pitch smaller ideas until you have proven yourself and earned more power or credibility (which is a kind of power). Look for who else is pitching ideas and what results they get. Pay attention to what arguments work in your culture.

Q: Is Microsoft an imitator? Given your experience here and elsewhere, how do you view the perception of MSFT and other companies as innovators or imitators?

Study the history of any idea and the notion of originators and imitators gets fuzzy fast. Neither Microsoft nor Apple invented any of: GUIs, Mice, Web browsers, Digital music players, cell phones, touch-screens, video games, icons, ethernet, Wireless networking, windows/menus, multi-tasking OSes, and on it goes. An entire chapter of the Myths of innovation explains how futile it is to worry so much about being first. How about being good? Making the best thing or the best manifestation of an idea? It’s a more potent criticism of Microsoft to say their products are bad or hard to use. Or boring. Or unreliable. Those are criticisms of design attributes that might lead to productive conversations.

Regarding being first, consider the i-pod and i-phone. The i-pod is a fantastic design for a portable music player but it’s far from the first implementation of the idea (The Sony walkman doesn’t get mentioned nearly enough in that conversation). The i-phone is far from the first cell-phone, and probably the 500th design of a telephone. Who cares who was first? Most of the time I don’t. History favors people who do things well, more than who does them first. Edison and Ford weren’t technically first with the idea for light bulbs or cars. Do you care? Probably not.

For this reason critiques like Microsoft The Innovator? that try to prove Microsoft is not innovative are just silly. Apple doesn’t show up well either as the first originator of big ideas in technology. Few major corporations ever do. By the time it’s in productizable form, an idea has been touched by many many people and often many different companies. And the skills required to manage a mass market product are very different than those required to invent a new kind of mass market product.

What I think people mean to say about Microsoft, really, is that their products are never inspiring to consumers. They do not generate excitement in the way people think innovations are supposed to. Instead they have earned a reputation for being generic, bland and corporate, with lots of blue and gray and little personality. This is hard to refute (There are exceptions, like XBOX, Encarta, Citysearch, Expedia, and Zune, but Microsoft has never used PR and branding to promote them as more than that). Stereotypically when Microsoft enters a market behind other companies they do little to differentiate themselves in consumer visible ways. They match features, offer generic branding, and chase. Microsoft has always been great at the chase. Part of the reason is that Microsoft has always been mostly a mediocre products company, but a strong platforms company. The big bets are not on the products, but on the strategies behind the products, which explains the occasions they’ve been successful in markets with superior competing products: the superior business model won against a superior product.

Anyway, this is a fun question but it doesn’t lead anywhere practical unless you are a CEO. For the rest of us the best thing to focus on is making something great. Make a great thing. Fuck, make a good thing: half the companies out there can’t even do that. Don’t worry about being new, or who you are imitating (unless you’re breaking the law), just make something that solves a real problem for people and you’ll be way ahead of the curve. If you make a superior product it’s guaranteed some of your ideas with be seen as creative or original, but they’re most often found as a by-product of trying to solve a problem really well. Innovation as a concept is a red herring. It’s slippery, misleading and distracting. I use the word as little as possible and recommend you do too.

Q: What is the role of culture in making innovation happens? Are there really as many recluses and lone geniuses as we think?

Easy one first: true recluses are rare. Most famous genius types had friends and collaborators whose role is often ignored in our hero worship. They had parents, friends, and sometimes even collaborators. Isaac Newton, one of the most reclusive of the recluses, had allies in the Royal Academy of Science that helped publish his papers and advocate his interests.

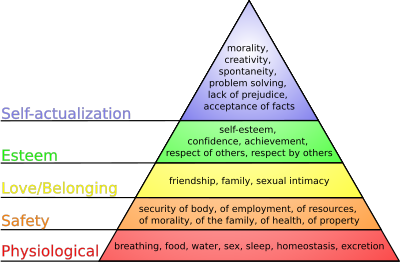

Thinking as a manager, culture is everything. If you think of ideas as a kind of wildlife, only certain types of environments are habitable by ideas. The job of any manager or leader is to create an environment for ideas to thrive. In chapter 7 of the Myths of Innovation I break creative culture into the following elements: Life of ideas, environment, protection, execution, and persuasion. Many of the famous centers of innovation in history scored well on these factors and the book explores some of those stories. If you’re culture is idea-averse, or loves to shoot down ideas quickly, you could have DaVinci and Einstein on your squad and invent nothing. The corporate world should be hiring more anthropologists to help us see the cultures we’re unintentionally making.

Have more questions on Microsoft, Innovation or culture? Fire away in the comments.

The

The