Book review: Walden, by Thoreau

Some books are referenced so often that eventually you just have to go and read them, just so you can challenge people who use the book as leverage in an argument. Thoreau’s Walden was on that list, and I read it recently. Here’s my review.

It’s a curious book. It’s well known in our environmentally aware age, to be about a person who spent years living in the woods, in harmony with nature. But that’s not quite the reality of the text. Early in the book Thoreau makes clear his spot in the Walden woods, donated by a friend (Emerson), is just a few miles from town. He was not a hard core hermit or back to nature zealot, as one might assume. His ambitions were more philosophical than tied to a specific set of rules for what nature is, or how often he could talk to people or have them over for dinner. It was an inquiry, a thought experiment, and arguably an American pioneer in self-discovery and taking responsibility for learning how to live. This idea is popular today, perhaps in slicker form, in books where people spend a year following the bible or traveling by bicycle to see what happens.

I was surprised by the three distinct themes I found in the book.

One is an attempt to provide a do it yourself guide. There are several lists of things purchased with prices and sources. Thoreau is thrifty and proud. He refers to how inexpensive his life is often, and there are long stretches where he describes, on a line item basis, how much it cost to build, supply and maintain his house. It seems he had some interest in providing a how to manual of sorts, but he gets lost in his ideas. Kind of like a lonely shop clerk who keeps telling personal stories instead of getting you the ham sandwich, sitting in front of him on the counter, you came into the store for. And the details don’t age well as a practical guide as the prices for nails have gone up, and home depot puts a new spin on what it means to do it yourself. There are frequent journal style mentions of hunts, food procured from his garden, and other daily facts of his existence.

The second theme is transcendent prose. This was what I hoped for. He was a student of Emerson and it shows, with page long riffs on the strange nature of man, the potential for greatness, the limits of our cities and times, and on they go. Some of these totally rock:

There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes after work. But it is a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things.

As for the pyramids, there is nothing to wonder at in them as much as the fact that so many men could be found degraded enough to spend their lives constructing a tomb for some ambitious booby, whom it would have been wiser and manlier to have drowned in the Nile and then given his body to the dogs.

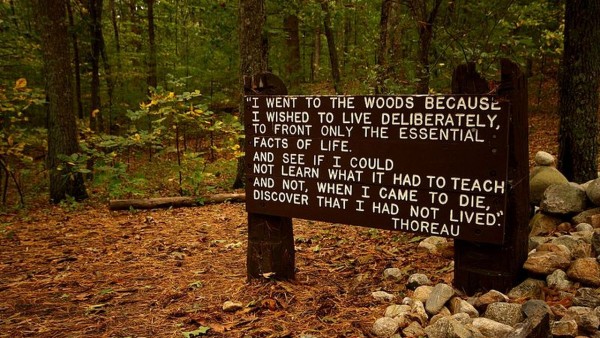

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.

The millions are awake enough for physical labor; but only one in a million is awake enough for effective intellectual exertion, only one in a hundred millions to a poetic or divine life. To be awake is to be alive. I have never yet met a man who was quite awake. How could I look him in the face?

These are moving, potent, memorable words. If Thoreau achieved his goal of transcending normal existence through a return to nature, and sharing that experience with the reader, it comes through in these passages.

But the third theme of the book is thick, meandering, writing. He runs with the same rambling narrative for pages at a time, beating his own point into the ground or losing it altogether. Anne Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek captures the experience of being alone in the woods with a completeness well beyond Thoreau’s, simply because she provides a consistent, reliable and intensely fascinating narrative. Thoreau seems like the kind of fellow who spent too much time on his own, and his wandering mind, unaware of the confusion he creates in the minds of others, rambles around on its own selfish whims. He was a true recluse and I think it shows. Emerson, though long-winded, keeps his points in straight lines. Thoreau writes like strings of thread, thrilling when they lead somewhere interesting, but often they just get tangled up so tightly you wish he’d take more frequent care to tie them up into neat, memorable bows.

For a short book it is not tightly written and although it has great themes, I find it hard to call it a great read. And Emerson, for all his own verbosity, should have suggested more edits in Thoreau’s work than it seems he did (I understand Emerson played a key role in getting the book published at all, but I can’t find the reference). Perhaps I came to Walden too late, having read many books clearly influenced by Thoreau’s work. And although I respect the fact the book was written more than a hundred years before I was born, I can read Emerson’s collected essays with fewer complaints.

Check it out for yourself: Walden, by Thoreau. This is an online, and annotated edition.

I tend to avoid annotated editions on first reads, so here’s the edition I used: Walden, by Thoreau (amazon), which includes his famous essay on Civil Disobedience that inspired Gandhi and MLK.

[Edited 8-8-16]

Paul,

I would concur on much of this. I haven’t read Thoreau as recently as you, but once thing I remember clearly was that he did not go into the woods in order to write a book. He went into the woods, and a book resulted.

My emphasis here addresses your third point – Thoreau wrote this as much for himself as for literary lineage. I would this this (set of) essay(s) represents his journal more than something he hoped to publish. For this reason, I think we (readers) should focus on your first two points rather than the nature of the writing.

I know if I took the ramblings of my journals and put them to press, they would be even thicker and more challenging to pull useful material from. Brains aren’t wired to write prose in the moment, but to create ideas from which prose may be drawn. And, to conclude this stream of conscious response, it seemed that was the ultimate point you were getting to.

m/.

Thoreau made many revisions before Walden was published. If you find it meandering, you certainly can’t claim it’s because it was ‘just a journal.’ What you read is exactly what he wanted you to read.

Good to know. Thanks.

I am reading Walden. Like the reviewer, I came late to the book after hearing so much praise. It was very popular and on the lips of many for a time when I was a younger woman. I am 69 years old.

Already, I am put off by how full of himself Thoreau appears. I get his valid points about living simply and the waste of time spent on material items. He does make some poignant arguments, some of which appear full of compassion. Yet, he can’t quite stop himself from condescension toward others. It isn’t the rambling that offends me so much as the sanctimonious “thank God I’m not like the rest of man.”

Thoreau makes an effort to be helpful and to encourage his fellow man to think, but his criticisms seem shallow even for his time. It’s as if he lacks the understanding of the real why of man’s behavior. The problem appears that he thinks he knows the why and has no compunction toward provocation. I can visualize where some in his day might take umbrage with his logic–although perhaps that is the point.

On the other hand, his sympathies for the abused and downtrodden is exemplary and needs to be voiced in every age. I wonder too, if some of his examples are tongue-in-cheek as he does point out humorously the ludicrous, unquestioning routines in which man embroils himself.

Yet, I read Thoreau in small doses. I don’t dislike him, just a little disappointed in the product. Perhaps, the expectations were too high from the onset.

Thoreau had a reputation for having an odd personality, an it comes through in the book, I agree. It’s hard to read a classic without preconceptions that the writer didn’t invent or create, so a writer I try hard to give other writers the benefit of those assumptions. It’s a good book even with its faults. I’m glad it became popular.

I agree with Mike for the most part. I’m finishing Walden, and for me Thoreau’s immediate thoughts (without all the careful polishing and honing that Emerson adored)are priceless. It’s stressed by many, my English teacher included, that Walden is not a novel in any way. I do see what you mean about the rambling though, which can initially get irritating. But upon rereading certain passages, you start to distinguish the more essential ideas and connections to previous topics more easily.

Also, I’ve never been to this site and only found it because I had to search “book reviews walden” to see how other people interpret it. It was incredibly depressing to search numerous book review sites for “Thoreau” and find no results.

): I blame my generation, I think.

I thought Walden had a great start, but Thoreau’s repeated digressions left me frustrated. I think the first third is really good, but the last two-thirds not so good. It never occurred to me, like you point out, that Thoreau may have been going a bit stir-crazy alone in the woods (although he frequently punctuated his time there with visits with Emerson). I think though it deserves its reputation as a great read for the quality of his quotes: “Most men live lives of quiet desperation” and his desire to expose himself to the harshness of life and reduce life to its necessities. An inspiring read.

Thanks for sharing that honest review. I think I’m ready to start my first Thoreau inspired work. Any recommendations?

probably none of his books and none of his poems or work it is boring and silly.

Agreed with your thoughts about the book being tightly written. I find Thoreau’s writing particularly interesting in that he will allow himself to ramble on for a time, sometimes for pages, before arriving at a point. Other times his writing will be so dense with philosophy that there is almost no space between. I rather enjoyed the journey he took me on, in a sense, by not editing some of the more wordy sections and allowing me to explore the idea with him while he tries to arrive at the destination.

Book publishing in the 19th century was very different than it is today. It’d be far harder to work with a major publisher and have books ramble and meander in the way they did back then, for better and worse.

There were great writers of Thoreau’s generation who did not ramble or meander. To be blunt, it’s hard for me to credit Thoreau’s time at Walden as a source for his work’s insights. To include in his tortured, indefatigably selfperpetuating prose the sentence “Simplify, simplify!” makes it unlikely he had any insight at all. His transcendentalist ideas must have come from Emerson, his prose from some other crop inadvertently mixed in with his beans.

Why is Walden so popular then? There must be something about it.

Maybe the paths to and phrasing of his thoughts is the interesting part here, rather than the pure insights.

I tried to read this book, as it was chosen for my book club. I tried but failed to finish. If there is no relationship to consider, no service to ones fellow beings, no connection to the joys and hardships of living a life with other people, then what is the point? What would the world be like if everyone lived as a hermit, thinking about how everyone else is either right or wrong in their thinking? It’s the doing and loving that make a difference.

Thoreau is definitely a bummer in some ways. He’s kind of a snob? It’s also apparently true that he wasn’t all that remote, which I mentioned in my post. Anyway, I’m all for abandoning books that don’t work. There’s little value in pushing through something that really isn’t connecting. Although sometimes, in a different mood, the same book or movie can land differently.