Understanding Apple (Apple now the #1 Music retailer)

According to Apple, over January and February of this year they surpassed Wal-Mart as the largest music retailer in the U.S.

Here’s why this is amazing:

- The itunes store is only 5 years old. FIVE YEARS.

- According to Apple, they account for 70% of all digital music sales.

- The ipod is the market leader with ~75% of all music player sales.

- Apple was a late entrant: they did not invent the first digital music player, nor the first digital music store.

The most important but rarely told story is that Apple is no longer a niche brand. When else in history has a BMW, a Rolex, a Four Seasons, successfully transitioned into a Honda, a Timex, or a Holiday Inn? It’s rare. When high-end brands go mass market, they rarely get it right. But Apple made the transition in a handful of years without anyone even noticing.

And more interesting to students of innovation is how the story line around Apple is still about innovation despite the gaps in the stereotype. It’s rarely mentioned how they were late to the digital music game, how many of the technological breakthroughs were done out of house, or how many mistakes competitors made that accelerated the rise of the i-pod and i-tunes so fast.

It’s thrilling to see a company thrive on maintaining their standards, and entertaining to see the late followers respond. But the true innovation at work here, if it can really be called an innovation, is quality. The distinction of the Apple brand is superior aesthetic, functional and design quality, and Apple has succeeded in making quality the distinctive factor in tech purchasing decisions. Not price. Not features. But quality. And the irony is how competitors refuse to compete on this turf, retreating back to price and features.

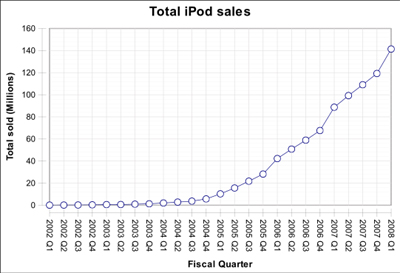

Perhaps the most important overlooked point lesson in all this success is how unexpected it was. I doubt any marketing projection for i-tunes or the i-pod had anything like the adoption curves seen above. I suspect they predicted they’d maintain their high-end brand with it’s resulting high-end marketshare, and were as surprised as the rest of the world with how quickly the i-pod became a phenomenon. For all their well deserved success, Apple still experiences the unexpected.

The recent

The recent

I’ll be doing two sessions at this year’s

I’ll be doing two sessions at this year’s