Banning Something Makes It Powerful

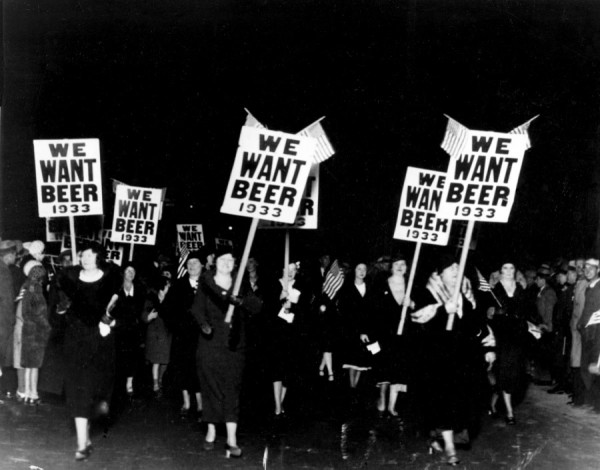

Today is the 80th anniversary of the repeal of the American prohibition of alcohol, and it serves as an excellent example of unintended consequences. For 13 long years alcohol was illegal, but early in prohibition it was clear the law change didn’t have the intended effects. Alcohol became more powerful in many ways, and since the mechanisms by which people obtained it were illegal, some of the cultural problems prohibition was expected to solve got worse.

Today is the 80th anniversary of the repeal of the American prohibition of alcohol, and it serves as an excellent example of unintended consequences. For 13 long years alcohol was illegal, but early in prohibition it was clear the law change didn’t have the intended effects. Alcohol became more powerful in many ways, and since the mechanisms by which people obtained it were illegal, some of the cultural problems prohibition was expected to solve got worse.

Most bans in free countries today regard media: books, films, music and ideas. In most cases the announcement of a ban is free-PR for all of the people who are probably interested in the thing being banned who might not have heard of it if the ban didn’t happen. Most media love telling the story of things being banned, since it earns intense interest from both the people who agree with the ban and the people who are upset by it. Every time a parents group bans an album, or a religious organization bans a film, the film itself becomes far more powerful. Rather than a ban being a bad thing for an artist, it can often be a catalyst for their ideas and you can often see artists deliberately trying to manipulate this cycle to their advantage.

The same principles holds true among parents and children, or managers and employees. The more something is withheld, the more power and meaning it gains. For the powerless in these situations the banned item becomes a symbol of their lack of control, and their interest in it can only grow. Banning something gives that thing a personal meaning beyond whatever attributes the thing inherently has. Forbidden fruit often only tastes better than regular fruit because of what’s in the mind of the person eating it, rather than what’s in the fruit itself.

A ban is lazy policy. It’s a failure to examine causes and effects of human behavior, including the history of the causes and effects of banning things. It’s entertaining to learn the earliest known prohibition of alcohol was by Yu The Great in China in 2100 BCE, and surprise: his son ended the prohibition when he took over. Had Yu been great enough to develop a more mature and reasoned policy, his son might have embraced it.

Related:

- A brief history of stupid book bans in America

- Banned books that shaped America (Bradbury’s Farenheit 451, a book about a culture than burns books, was ironically banned)

- List of banned books by country

- Time to End the War On Drugs

- PBS On Prohibition

I disagree on two counts:

1) Banning things doesn’t make them powerful; rather it makes their (potential) power clear. The expected power of the thing becomes the codified power of the thing, which is why a legal, moral, or social code was implemented against it. (Exception: There is substantial irony in this arrangement if the alleged power was actually *projected into* the thing by fear, only to have it codified as reality by the prohibition; see also “religions that don’t believe in magic but insist on burning witches.”)

2) I mentioned potential power because things, like data (per your earlier post) are just things — they don’t act on their own. In the case of Prohibition, the least scrupulous people found a profitable way to concentrate, seize, and exercise market power — with the concentration of that power being made possible by the ban forcing nice people to leave the playing field. (The Seattle Ignite last month had a speaker advocating for pot farmers on this basis, in reverse — quite a compelling argument.)

The market concentration to the unscrupulous actors that bans allow for clarifies (and may also amplify by the actors involved) the latent capabilities and potentialities of the banned Stuff.

To put it another (entirely hypothetical) way: You could OD on crystal meth even if it were legal, but you’re more likely to get shot while buying it because it isn’t legal, and all of this is cable-news-worthy because it isn’t legal.

The Alcohol prohibition in America is interesting in part because of how odd it was that it happened at all. It was the perhaps the first lobbying group, or first lobbying group in the U.S. that focused so narrowly on one specific objective.

I’m not sure if you’re points are about semantics or not. I agree that like my thoughts on data, a ban is just a bunch of words and has no consciousness.

My point was that at the moment a thing is banned it becomes more interesting to more people, and therefore more powerful, than it probably was before the ban. It lends more power and a larger platform to speak from for whoever is most impacted by the ban than the probably had before. Of course these ramifications are all based on people’s responses, but my point is in the long history of banning things in free societies (and in some cases even in closed ones) these effects from a ban are predictable.

U.S. Prohibition isn’t the best example of my point because of how complex and specific that story is. A better example might be the drinking age in America compared to Europe, and the culture of binge drinking we have here. Based on my hypothesis if we eliminated the drinking age, or reduced it, or as parents let young adults try beer and wine before it was legally available to them as individuals, and made drinking far less of a forbidden fruit in American culture we might see less abuse of it young adults, since we’d eliminate the years of anticipation of some magical transformative day when they’d be able to drink.

Half-semantics. Whatever power is there *is* there, it’s just that banning it brings it into sharp focus with all of the predictable downstream (and people-driven) impacts that you correctly highlight. But hey, let’s spend some more time with this.

My preferred thought experiment would be “making it hard to access the internet at work results in somebody breaking policy with an open wi-fi router that promptly gets hacked and exposes company info to Those People Over There, and yet the co-workers hate the IT internet access restrictions rather than the idiot who inadvertently opened up the company.” But that’s neither here nor there (yet).

To focus specifically on the drinking age, I can say with good confidence that we wouldn’t see substantially less alcohol abuse among teenagers as the primary abusers are driven by a profound lack of power coming into contact with a need to prove an ability to wield power and establish independence — I totally agree with Paul Graham on the socioeconomic strangeness of adolescence in America, though Adam Kotsko’s tweet (RT via @SeriousPony) sums up the bizarro-ness nicely:

“We ask 18-year-olds to make huge decisions about their career and financial future, when a month ago they had to ask to go to the bathroom.”

Put simply, that would drive me to drink too. And wanting the students that I coach to not show up to competitions hung-over, I try to treat them like inexperienced adults. This has its limits — they do still sometimes think like children — but it shifts my role from dictating decisions to providing a sort of “artificial experience” in the hopes of getting them past the common bad decisions of youth (like disempowered binge drinking) and on to new creative errors (that I couldn’t have predicted).

But I’m wandering off-topic; they key is that the binge drinkers are not the ones who are in awe of the booze taboo. The binge drinkers (initially) are the ones who have easy access to alcohol and don’t grasp the arbitrariness of the prohibition (and don’t suffer consequences past the hangover as demonstrated by the reports of Wild Parties vs. reports of Kids Cited For Underage Drinking). Similarly, it’s not people who are awed by getting network access that would set up a rogue wi-fi router in the office but rather the person for whom not having access is unnatural.

But let’s go further: if I am not held by a taboo — say, for example, a taboo against bringing my students chocolate chip cookies — and everybody else is, then I can elevate my social power by demonstrating that I am not bound by the taboo that binds them above and beyond how much they appreciate the delicious chocolate chip cookies: I am above the law that is above them. Similarly, kids who are cowed by the booze taboo will be easily subjected to peer pressure from kids who pay the booze taboo no mind and are happily putting additives in their hot cocoa. And this is also why the idiot with the rogue wi-fi router (taboo breaker) is held in higher esteem by the taboo-abiding colleagues than the IT department that maintained the taboo.

But let’s go back to the kids: one kid doesn’t respect the taboo and has means and opportunity to binge drink and their friend is cowed by the taboo and thus awed by the taboo-breaker. This is a situation where your thesis is apparently correct: instead of 1 inebriated teenager, we’re probably about to have 2, and we can blame that 100% difference on the de-contextualized prohibition on under-age drinking (aka taboo). But we had to have a taboo-ignorer with means & opportunity to break the taboo before downstream impacts occurred (which is my point). And to the point where our society has opted to ban a symptom of a problem — alienation and disempowerment leading to people trying to avoid engagement with reality — instead of actually addressing the problem, then the ban has increased power where power should not have been increased. But at a wider level, blaming the ban gives the ban that same power that we didn’t want it conveying on the banned Whatnot. Fun!

Here’s some other stuff I said about what adults don’t want to think about teenagers doing: http://www.lexwerks.com/article/sex-death-narrated/

> Half-semantics. Whatever power is there *is* there, it’s just that banning it brings it into sharp focus

Ah! I understand your point now. Thanks for clarifying.

This is interesting thinking – far deeper than what I offer in the post. I’ll need to think more about what you’re written here to form an opinion about it, but I will. And I’ll also check out your other post you listed.

What I was after was a simpler point – I considered using was Miley Cyrus and twerking as an example. Had no one expressed outrage about her performance it wouldn’t have been a cultural event, but the outrage fueled far more interest in the “outrageous” thing than there would have been otherwise. Outrage isn’t the same as a ban, but it’s in the same category as far as the point I was trying to make which was, perhaps more concisely: attention is power and negative attention to a thing can grant it more power than it would have if you ignored it. Not always, but often.

> I can say with good confidence that we wouldn’t see substantially

> less alcohol abuse among teenagers as the

> primary abusers are driven by a profound lack of

> power coming into contact with a need to prove an

> ability to wield power and establish independence

My primary examples are adolescents in Europe, where generally alcohol is dealt with in a more mature fashion. I admit it’s hard to isolate one factor when comparing cultures, but if you pressed me for data to support my claim that’s where I’d start looking.

banning things make you want to do that more it doesnt make it more powerful it makes you more likely to want to do it

Hi Scott, I won’t speak directly on power—you’ve touched my nerves.

My pet peeve is people who refer to U.S. Prohibition as proof that banning never works. Peter Drucker called Prohibition the work of a single-issue group, a group who would ignore all the other complexities of democracy to instead evaluate who to vote for based on their single issue. Drucker saw such groups as parasites. The rest of the public sensed this, I think, hence the story of the politician who publicly drank on the same day the bill was passed, without losing the esteem of his constituents.

My dad’s grandmother back then did not wish for help, or incentives and rewards, in abstaining from her evening whiskey.

Before “giving power” comes the decision to ban, and before that it can be helpful, I suppose, to think in terms of “bribe or reward.” Semantically, a bribe is to get someone to do something he would not otherwise do; a reward is to get him to do something he already wants to do.

In the novel The Puppet Masters a man who leads patriots to their deaths defends himself to his son against the charge of “puppet master” by saying, “I lead men in the direction they already wish to go.” …I’ve been thinking over that one for years.

Sometimes, things become famous only because they are banned.

Salman Rushdie comes to mind- his books are so boring, I have never been able to read past the 1st 10 pages. Midnights Children was based on a topic I love, but again it was as fun as watching paint dry.

A part of me wonders: The best thing the clerics could have done was to ignore Rushdie, and that would have destroyed him. Instead, he has become a celebrity.

Checking Wikipedia, Midnight’s Children “won both the Booker Prize and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1981”, so Salman Rushdie was an acclaimed author years before The Satanic Verses. He was far from being ignored.

Germany bans Holocaust denial publications (to simplify). So does Canada and some other places. Is there any evidence that this ban has resulted in greater power for such publications?

Often people say that if currently illegal drugs were just legalized, the problem with cartels would just go away. I’m doubtful. The cartels have already diversified to human trafficking, smuggling, and who knows what else. I think that it’s far from clear that the “bad guys” would just throw up their hands, give up “bad” occupations, and take up something positive. (Not to say there may not be other arguments for legalization, but I’m doubtful the cartels will disappear because of it.)

It’s true Rushdie already had literary fame, however it was the drama around the Satanic Verses that made him a household name.

Rebekah Price informed me that Mother Teresa once said:

“I was once asked why I don’t participate in anti-war demonstrations. I said that I will never do that, but as soon as you have a pro-peace rally, I’ll be there.”

http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/690241-i-was-once-asked-why-i-don-t-participate-in-anti-war.”

Reading up on the Iceland/Greenpeace ad led me to this blog. Being a marketeer, I am fascinated by the power of publicity, good or bad, on commercial endeavors as well as sociopolitical issues. I was amused to find that in recent times this has become known as the Streisand Effect, which is also a great made-for-TV movie title

https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2013/04/15/what-is-the-streisand-effect