One of the many jokes about Powerpoint is how much time people who use it spend picking transitions between slides. They spend more time picking out animations and fonts than what their audience needs to learn and how best to convey those lessons. It’s like wanting to make a movie and spending all your budget just on costumes. It’s backwards and broken.

Because of how Powerpoint, and Keynote, are constructed, common habits for creating presentations are often poor. The tools are slide centric, not presentation centric, and people instinctively follow the metaphor built in to their tools. While I do believe you can make a good presentation with any tool, and a bad one too, the emphasis of the tool influences choices.

Popular presentation tools focus on slides, which should not be the focus at all. No one comes to listen to a lecture in hope of great slides. They want good ideas, expressed well, especially ideas that answer the questions that motivated them to attend the lecture in the first place. Most people I know, when informed they need to give a presentation, immediately begin making slides, and they may as well tie a noose around their own necks. There is no point in making a single slide until you know some of what you want to say, and how best to say it. If you make slides first, you become a slide slave. You will spend all your time perfecting your slides, instead of perfecting your thoughts. You will likely talk to your slides when you present, and not your audience, as you will have spent more time on the slides than you did practicing giving the talk itself. Sadly, I don’t know of any tool that guides their users properly towards how good speakers prepare.

In Chapter 5 of Confessions of a Public Speaker, I explain the best way to prepare for a presentation. You start by thinking about the audience:

- Why are they coming to the talk instead of doing something else more fun?

- What questions are they hoping you will answer about the topic?

- What are your well thought out answers?

- What is the best way to express those answers?

Only after some hard thinking on these questions is there any hope a presentation will turn out well, and it’s only then that a speaker should start thinking about slides. And even then, slides should be a tool for drafting. Make the quickest and dirtiest slides possible, and then start practicing the talk. After each practice, improve how well the slides support what you want to say. Only then will the slides have the proper role as a prop, rather being the star and making you the prop.

I first saw a demo of Prezi years ago, and it seemed interesting. I liked the idea of a fully 2D space to work from. But as I used it I realized it had taken the things I hated most about Powerpoint, and emphasized them. Prezi bills itself on the ability to ZOOM, to MOVE, to TRANSITION. All the most distracting elements for would-be speakers, elements that distract them away from the quality thinking required to speak well. Instead of thinking “I’m so proud of how I worked hard to explain this important idea so that my audience can understand it” they think “Here comes my favorite transition! Look at how the entire screen is going to rotate!” I can see how, in the hands of a skilled communicator, Prezi makes some things easier to do, but a skilled communicator would do just fine with any tool.

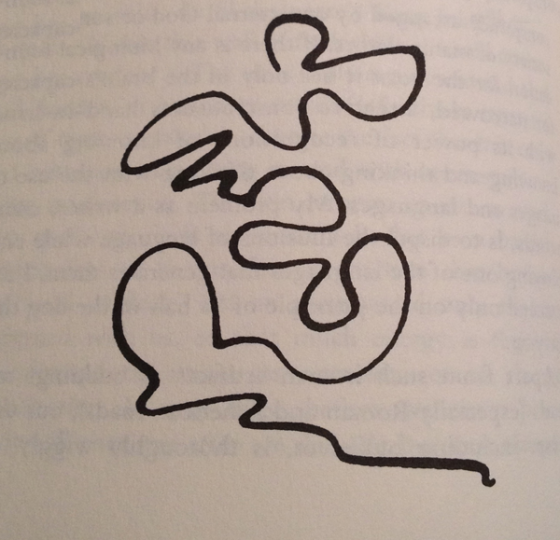

I’ve experimented with many different ways to present. If I want to have more control over how to represent things in 2D, I use a WHITEBOARD. Hooking up an iPad with a drawing app works wonderfully well as a virtual one. And it’s easy to switch between it and Keynote if I want to follow the basic structure of a slide deck. I was deeply inspired by watching Bill Verplank speak at UIE years ago, where he simply drew as he talked. It was more dynamic than any software, and more personal too, since we all could watch him work with his hands. He’s not a dynamic speaker, but he doesn’t need to be, as the clarity and value of his ideas are strong enough on their own. I can’t draw like Bill can, but I’ve found working with a whiteboard, virtual or not, invites an audience’s attention in a way software can never do. And as a speaker if I work at a whiteboard, I can’t hide behind slides. It forces me to properly prepare too.

The people most drawn to use Prezi are those who are more enchanted by the pretense of style, rather than substance. To this day I have yet to see a Prezi presentation that would not have been better had the speaker used something else, including nothing at all. Many presentations would be better if the speaker just spoke, sans slides or any props at all. If they just spoke, they’d be forced to think hard about what they wanted to say, and not expect to hide behind whizzy transitions or obfuscated slides.

If anyone has seen a great talk done with Prezi, please leave a comment.

[Updated Note 2-3-15]: here is an excellent post on the problems with misusing transitions in Prezi and how to fix them. I still don’t recommend the tool, but this may help those who choose to use it anyway]

[Minor edits 1-12-2016]

Once again Seattle Ignite is venturing outside for a special family friendly event. If you’ve never been before, this is a great time to come. Each speaker has 5 minutes to talk about something important and interesting. If one of them is bad, don’t worry, by the time you notice they’ll be almost done. And if you love what one of them had to say, you can fiddle with your phone and learn more about them and their ideas. It’s fun, its fast, it’s friendly. And it will change how you think about how public speaking should be done.

Once again Seattle Ignite is venturing outside for a special family friendly event. If you’ve never been before, this is a great time to come. Each speaker has 5 minutes to talk about something important and interesting. If one of them is bad, don’t worry, by the time you notice they’ll be almost done. And if you love what one of them had to say, you can fiddle with your phone and learn more about them and their ideas. It’s fun, its fast, it’s friendly. And it will change how you think about how public speaking should be done. In our own experience we know there are complicated reasons why bad things happen. It’s rarely one thing or one person. But yet when we blame others, we’re very happy to dump all the responsibility on a single person and rarely take time to investigate if they deserve it, which they almost never do. We pick an easy, defenseless target, and all the responsibility collapses on them. The rest of the story fades from memory.

In our own experience we know there are complicated reasons why bad things happen. It’s rarely one thing or one person. But yet when we blame others, we’re very happy to dump all the responsibility on a single person and rarely take time to investigate if they deserve it, which they almost never do. We pick an easy, defenseless target, and all the responsibility collapses on them. The rest of the story fades from memory.