I’m an introvert. I like being an introvert. I’m glad someone is clarifying what introverts are or are not, which is part of what Susan Cain does in her New York Times Article, The rise of the new Groupthink. However she’s careless in how she makes her case (even though I agree with some of it).

For starters to say “I’m an intro/extrovert” is an overstatement. We all behave differently in different situations and can be more or less extroverted for many different reasons. Many people think I’m an extrovert because I give lectures, like fun debate over beers, and can be a big part of a conversation or a party. But often I’m not that way, and can sit a corner and happily observe or read for hours. I’m the same person in both cases, just in a different mood, situation or atmosphere. It’s a false dichotomy to assume because I am introverted in one situation that I am introverted in all. The main factor is if I’m around people I know and like or not, which speaks volumes about coworkers and shared workspaces.

She writes:

Our companies, our schools and our culture are in thrall to an idea I call the New Groupthink, which holds that creativity and achievement come from an oddly gregarious place. Most of us now work in teams, in offices without walls, for managers who prize people skills above all. Lone geniuses are out. Collaboration is in.

Groupthink is a term coined in 1972 by Irving Janis. He described it as: “A mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action”.

First, you’ll find his definition and Cain’s diverge. He focused on crisises caused by groupthink (especially military ones, like Pearl Harbor and The Bay of Pigs Invasion), rather than the passive negative effects it has on a culture at large (which is what Cain is after). But this passive cultural notion is what has become the popular use of the term for a long time.

However, I don’t recall there being a time between 1972 and 2012, or possibly ever, when the culture in the business world had swung heavily towards radical individualism. The was no period of “Solothink”, where we went too far towards individual isolated creativity, and are now trending back the other way to a “New Groupthink”. Staking claims of big trends is self-aggrandizing and is a good way to get attention for selling books or getting web traffic, but that’s about it. Collectivism is a natural consequence of being social creatures that lived for eons in tribes.

Second, lone geniuses have never been “in”. Not in science. Not in art. Not anywhere. Lone geniuses have always had a hard time because they were loners, and for any idea to gain traction requires other people to want to listen to you, listening being something we more easily grant to people we know and like. Lone geniuses have always been more prone to being outcasts since great ideas force change, and most cultures, and the powerful people in those cultures, naturally want status quo. The lone geniuses whose names we know had teachers, partners, agents and supporters who made their work known: even the most introverted loner genius we know of was not truly alone.

Cain writes:

Research strongly suggests that people are more creative when they enjoy privacy and freedom from interruption. And the most spectacularly creative people in many fields are often introverted, according to studies by the psychologists Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Gregory Feist.In other words, a person sitting quietly under a tree in the backyard, while everyone else is clinking glasses on the patio, is more likely to have an apple land on his head. (Newton was one of the world’s great introverts: William Wordsworth described him as “A mind for ever/ Voyaging through strange seas of Thought, alone.”)

Newton was never hit by an apple, and likely most of the apple story is false. But that’s fine, as many people don’t know the truth there.

But I couldn’t find the Csikszentmihalyi study she mentions (no specific reference is offered). Having read some of his work, I know he has found many creatives show both introverted and extroverted tendencies, just as most people do. But to her main point, she is overstating her claims. It’s definitely true some people are more creative when they are alone. But everyone is different. Many great creators were collaborators, and had their most famous ideas in the presence of their partners. For many it’s the back and forth of time alone, and time with others, that fuels most creative fires.

She presents another false dichotomy. There is no reason a person can’t have both solitude and interaction with others in balance. It’s not one or the other, ever. Or even as Alan Cooper has suggested, simply split the difference and work on creative projects in pairs.

She mentions Mr. Wozniak’s invention of the Apple computer, and his advice:

“the very best of them are artists. And artists work best alone …. I’m going to give you some advice that might be hard to take. That advice is: Work alone… Not on a committee. Not on a team.”

This is an anecdote from someone who prefers to work alone. I have no idea how much he has considered other people might be different from him or not, or which artists he’s talked to or studied. Artists in unavoidably collaborative fields like music and film would disagree with him.

There is a long and rich history of artists working together in shared spaces. Artist communes, artists retreats, artist studios. Edison’s Menlo park lab was filled with people much like Wozniak, and for most of them it was the most productive and creative period of their entire lives. Pick any garage based startup company in the history of Silicon Valley, and you’ll find a story of people working together, in confined spaces. I’m sure many of them needed more solitude at times than others, but to cast it as a binary choice, either work alone and be a genius, or work in an office and fail, isn’t based on any reasonable accouting of the history of invention or of art.

Anyone can go outside, or for a walk, or find some of their solitude on their own time. Better bosses wisely give employees control over environment (e.g. work from home, which is done by more U.S. employees now than ever before) and hours if it makes them more productive (including creative production), but good bosses of any kind are rare. I wouldn’t call this the rise of “The New Bossthink” epidemic, but there are some basic certainties undercutting her core premise.

And yet. The New Groupthink has overtaken our workplaces, our schools and our religious institutions. Anyone who has ever needed noise-canceling headphones in her own office or marked an online calendar with a fake meeting in order to escape yet another real one knows what I’m talking about. Virtually all American workers now spend time on teams and some 70 percent inhabit open-plan offices, in which no one has “a room of one’s own.” During the last decades, the average amount of space allotted to each employee shrank 300 square feet, from 500 square feet in the 1970s to 200 square feet in 2010.

It has not “overtaken our workplaces or schools”. Throughout the history of the U.S. high school class sizes in major urban areas have likely never averaged less than 20 people in this half century. By sheer logistics of the number of students, or employees, we have always been housed together in small spaces. She doesn’t cite her sources for office size, and the trend may be for the worse, but the basic notion we share space with other people is quite stable and old. Colleges, universities, and cities like NYC are so dense with people it’s very hard to find solitude relative to most of the planet. But all three are well known environments for creative cultures. Exactly how much solitude qualifies? Is it a coffeeshop? A table at the library? Or is a good pair of headphones, great tunes, and a comfortable chair sufficient for some people to achieve it? Solitude is personal, and that’s the problem with all the studies. They try to take an averaging of everyone, but there is no average person.

They might be a minority, but there are many examples of very creative output from companies that work in shared, open spaces. Valve, the game company known for Portal and Half-Life, has teams work in large shared rooms (video of their office here). Menlo park, Google, Facebook, Hewlett Packard, all worked in cramped group spaces, at least at first. Since there are some examples, the physical environment can’t be the only variable. What is it about Valve or other successful places that allows them to thrive independent of all the research Cain offers? I have my ideas, but I wish Cain offered hers.

The New Groupthink also shapes some of our most influential religious institutions. Many mega-churches feature extracurricular groups organized around every conceivable activity, from parenting to skateboarding to real estate, and expect worshipers to join in.

Churches and religious institutions are odd examples of independent thinking. People join churches to explicitly participate in group thinking, with shared beliefs and codes. They may be even more tightly controlled today, but the core basis for the church in the first place is a fundamental interest to share well defined and old thoughts/beliefs with others.

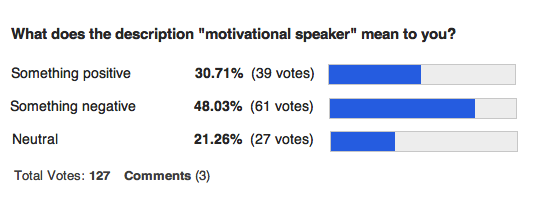

It’s been a bad month for Brainstorming consultants, as Susan Cain takes a page from Lerhrer, with big swings at Osborn and brainstorming:

But decades of research show that individuals almost always perform better than groups in both quality and quantity, and group performance gets worse as group size increases. The “evidence from science suggests that business people must be insane to use brainstorming groups,” wrote the organizational psychologist Adrian Furnham. “If you have talented and motivated people, they should be encouraged to work alone when creativity or efficiency is the highest priority.”

She doesn’t cite a specific study. At least Lehrer named the authors and the publication year for the studies he based his argument on. If a writer refers to a study, they should be obligated to allow the reader to follow their tracks (A name, a university, a year. Something). If they don’t want to bother then they can offer their own opinion, which would be fine. But to say “decades of research says” and give no references is problematic. Perhaps her book offers more support.

She ends with a moderate and balanced position which I can agree with:

To harness the energy that fuels both these drives, we need to move beyond the New Groupthink and embrace a more nuanced approach to creativity and learning. Our offices should encourage casual, cafe-style interactions, but allow people to disappear into personalized, private spaces when they want to be alone. Our schools should teach children to work with others, but also to work on their own for sustained periods of time. And we must recognize that introverts like Steve Wozniak need extra quiet and privacy to do their best work.