site changes in progress

scottberkun.com & scottberkun.com/blog are undergoing some changes over the next day – so if things are weird or pages 404, you know why.

scottberkun.com & scottberkun.com/blog are undergoing some changes over the next day – so if things are weird or pages 404, you know why.

The theme at etech was technology as magic, and many sessions took it head on. Seth Raphael‘s talk on Sufficiently advanced magic was my favorite session with the word magic in the title. He mixed up magic performance, entertainment and techno-philosophy and lived up to the conference theme.

The theme at etech was technology as magic, and many sessions took it head on. Seth Raphael‘s talk on Sufficiently advanced magic was my favorite session with the word magic in the title. He mixed up magic performance, entertainment and techno-philosophy and lived up to the conference theme.

Danah Boyd and Jane McGonigal asked the deepest questions at the conference, exploring the impact of technology on people but from two different perspectives (Danah explored the impact of social networking on people, especially less-technical people, and Jane challenged the audience to take responsibility for the things we make actually making people happier). I was happy these excellent sessions were about the impact of technology, rather than about technology itself (which often bores me to tears).

But some sessions went meta on the magic theme – They tried so hard to explain magic, offer philisophies on magic, or deconstruct how technology approximates magic, that there wasn’t much air left in the room – the sessions were decidedly unmagical and abstractly academic. I thought Seth did it right, but given how many smart people struggled to handle the topic he made it look easier than it was. David Brunton had it right in his talk on cellular automata, but the audience seemed stunned by what I thought was a very funny presentation.

And along the way, for some reason, the idea of UI metaphors got roughed up – in 3 of the sessions i saw they picked on the idea of metaphors – and I’ll offer a defense in a future blog post (hint: web pages, links and buttons are all metaphors).

Best demo: Paul and Lelia at Idee gave the best demo I saw: their image searching tool blew my mind. Otherwise I didn’t see much that stuck with me – there was commentary about emerging things, and talks on why X or Y should or shouldn’t emerge, but not that much in the memorable demo department. MSR had some great demos, including the children’s programming tool Boku (video) and a mobile web browser that doesn’t suck (no easy task).

I did a tutorial on How to innovate on time (Slides 4mb ppt) and a short talk on the myths of innovation – both were fun and had good crowds. Tom Coates was both bold and generous enough to correct my erroneous story of the origins of the word architect, but otherwise my tales of innovations past were well received.

Thanks to anyone who saw me speak and to Rael, Vee and the O’Reilly folks for having me there.

You can find Slides from other speakers can be found here plus coverage and photos.

Research labs are an old idea. Edison’s Menlo park lab in the 1870s had most of the elements innovation labs and R&D groups try to emulate today. But that doesn’t stop companies today from starting from scratch, assuming they’re the first to try. In researching the book the Myths of Innovation I studied how research labs in established companies work, and why they fail.

Here’s why in simple terms:

References:

The primary reason research labs fail is that successful innovation depends on variables beyond our control – you can do everything right and still not deliver the breakthrough everyone expects – a theme explored in depth in the Myths of Innovation.

The primary reason research labs fail is that successful innovation depends on variables beyond our control – you can do everything right and still not deliver the breakthrough everyone expects – a theme explored in depth in the Myths of Innovation.

Confession: I am in serious essay debt and I need your help to get out.

The story: I made a commitment when I quit MSFT in 2003 to publish an essay a month on the website. That’s 12 a year. Here are my stats:

So I owe the universe or myself (whomever cares more), 9 essays. That’s right. Not to mention the 3 so far this year that haven’t materialized yet.

I have plenty of ideas, but I’m bored with my ideas. I want yours. That way I’m guaranteed at least one person other than myself will give a shit when I post the thing.

So here’s your chance: If you could rent my brain to write something, what would the title of the essay be? What topic do you think I’m chicken to write about? What mean scary question do you want me to answer?

Lets get it on!

One habit many managers have is to dump the boring, unpleasant work of their team onto contract workers. The thinking is that full timers deserve the best treatment and contractors are mercenaries: they deserve whatever they get since they won’t be around long.

It’s a mistake – good managers finds a way to treat everyone well. And there are some reasons contractors deserve special attention:

Here are three reasons why:

I’ve seen dozens of smart people sequestered away in the worst offices, never asked for an opinion and given no opportunity to shine, simply because they wore the label “contractor” – what a waste for everyone. Some contractors run circles around their FT counterparts – in fact that’s why they’re contractors: they’re good enough to make a living freelancing and taking part of the year off something many full-timers (FT) don’t have the talent, or the guts, to do.

The fear managers have is that treating contractors the same as employees raises legal issues, or threatens the full timers, but that’s nonsense – you don’t have to treat them the same in order to treat them both well. And if your team is threatened by talent, you’re in trouble for different reasons.

The Myths of innovation book is wrapping up fast and it’s time to put together another crazy kick-ass no-frills book tour.

Stop 1: I’m planning to hit the bay-area for a few days in mid-May. For the last tour I spoke at Google, Yahoo, Adobe, Sun, Macromedia & Baychi. Do you have a venue and want me to come by? Now is the time to let me know.

Stop 2: I’ll also be doing local (Seattle) talks where-ever I can around the same time.

I can’t promise to stop everywhere, but if you can get a good, fun, (and hopefully book-purchasing minded) crowd together, I’ll definitely consider it.

The fine folks at Moscow’s IT-Online have invited me to teach a one day seminar on management April 25th (registration here).

I’ve never been to Russia before and I’m looking forward to it – and I’ll be in St. Petersburg for a few days – If you have travel advice for this part of the world I’d love to hear from you.

Most people I respect have little respect for software patents – they’ve either read one, have their name on some, or have paid attention to who is most served by their creation (IBM has more patents in it’s name for each of the last 14 years). In all my research for the book I found little hope that the patent office was due for reform, especially for software, and had little hope for change.

So I was stunned when I read that the U.S. Patent office is piloting a new process for patents.

The news so far is thin and I can’t find official comments yet (couldn’t find a thing on the USPTO site):

Washington Post

ZDNET

Interview w/Jon Dudas from USPTO

(Note: Dudas’ full job title is the Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the United States Patent and Trademark Office – his business cards must be 8×11).

Starting and stopping on time is easy. One person with power simply has to decide to care, the rest follows.

Having recently survived a tragicomic 8 way international conference call, an experience worthy of the 4th level of hell, I’m here to offer 5 honest tips that would have saved the day:

Also see, The 22 Minute Meeting.

You know a big word is in trouble when it’s used repeatedly (inconcievable!) – it means the person saying it doesn’t know what it means or isn’t saying anything at all.

In a recent Ford TV ad, the word innovation is used once every 8 seconds, a sure sign that the i-word has seen better days.

Today the word innovation is a common placeholder – Instead of saying “we are smart”, “we are good” or “we are willing to try new ideas”, messages that can be examined for truth, the word innovation is thrown down ambiguously, as if it were a replacement for having a message, or stating one clearly.

The goal of my upcoming bestselling book, The Myths of Innovation is to bring honor back to the word by exploring the history of true innovations, and demystifying the breakthroughs of the past and the present.

Along the way I’ve learned some easy ways to diminish innovation hype:

I had a blast speaking at Adaptive Path’s MX conference recently about the Myths of Innovation book. I had the closing slot which can be tough, but the crowd was great and gave me a chance to have some fun (podcast of this talk is coming)

One highlight was being interviewed by Sarah Nelson, a design strategist for AP.

To give a taste, and stumble into the postmodern idiocy of quoting someone quoting me:

SN: One of the things I’ve been wondering about is the idea of “source of innovation” within a company. Do you think it’s actually possible to create an environment in which innovation occurs?

SB: I think that you can create an environment, and it’s very simple… whoever has power over a budget, and whoever has power over what features are included in a product or go up on the website, they enable innovation by saying “yes.” That’s really the fundamental thing that they have to be willing to do.

When someone shows up with an idea — “Hey, why don’t we change the navigation system from this older design to this new design I’ve been thinking of? Can I get some money to go and prototype this?”

All that has to happen is the person with power says, “Yes, I will give you a week to go and prototype that and we will review it when you have the prototype, and then we’ll consider actually making those changes.” And once everyone witnesses the person in power saying “yes” to a new idea, then they’ll be comfortable bringing another idea, or a third idea. And then all of a sudden, you have an environment that is very receptive to new ideas and innovations.

Sounds obvious, but as I explain in the book these environments are rare.

In the parade of mis-represented research that is modern journalism, we have this short article from MSNBC, titled “Do meetings make us dumber?“.

The article starts with:

People have a harder time coming up with alternative solutions to a problem when they are part of a group, new research suggests.

Which people are these exactly? Articles, and research, treat people as uniform, while we all know the goodness or badness of meetings depends on who is there. If you had a conference call with Bono, Einstein, Dostoevsky, and Susan Sontag, I guarantee the meeting wouldn’t make you dumber.

While folks of their caliber aren’t clambering to join our meetings, it does stand that who controls the invite list holds the fate of the meeting in their hands.

And doesn’t the goal of a meeting impact the quality of what happens? As the articles states:

Scientists exposed study participants to one brand of soft drink then asked them to think of alternative brands. Alone, they came up with significantly more products than when they were grouped with two others.

Wow. I can’t think of a task more inspiring for creative thinking than listing brands of soda, can you? Isn’t that what Mozart, Walt Whitman and the Beatles did?

How can anyone think this is representative of what goes in in “creative” meetings, or is a viable, as science, to use in comparison to how people make decisions, or work in groups, in real life?

Two points of refutation:

The notion of group behavior harming creative thinking has a long history – the term groupthink coined in 1972, and it offers a more useful analysis that the MSNBC or the research study.

For reference:

– How to run a brainstorming meeting

(Link from Flee)

As proofreading goes on chapter by chapter, I get my last chance to review references and properly site cite sources. It’s slow, tedious, and so little fun, I thought I’d throw some of it at you.

The question: How many species in the history of the planet have gone extinct?

The web has been surprisingly stingy. The wikipedia entry for extinction pointed me back at mediocre sources I already had.

Obviously I don’t need hard data as there isn’t much: but a ripe quote from an expert, or a summary of expert opinions would be perfect.

The prize: find me a reference that I’m willing to use in the book, and I’ll put your name in the book’s acknowledgments.

What was it like when the world upgraded from sheets of paper to books? Well here’s one humorous version of what that must have been like.

(Link from author Douglas Smith )

btw: I’m looking to compile some innovation humor. If this made you think of other skits, cartoons or jokes, please leave a comment.

The best new tech sector event in Seattle is the Ignite series Brady Forest started a few months ago. It’s an open submission series of 5 minute talks, and it’s fun. The fact that it takes place in a bar on capital hill doesn’t hurt, and if you can get there early you can take part in a fun Make magazine competition (think flying eggs) run by Bre Petis.

Details, directions and agenda here. Unless you have plans, go.

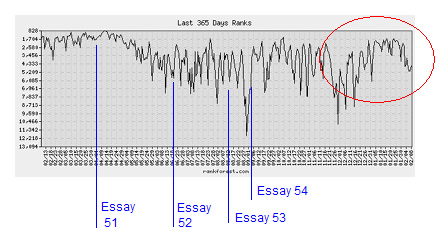

Months ago I described my experiences with book sales called the life of a book. Almost a year has gone by since then: time for an update for those curious about what it’s like on this side of the book.

Here are 12 months of amazon rankings for artofpm (courtesy of rankforest):

The bad news:

The good news:

Analysis:

What does all this mean? I don’t know. I though writing this post would help sort it all out: but there’s no easy explanation.

Thanks are due to anyone out there who has recommended the book to others. At this point the book is on its own, and its continued success comes from people telling others about it: so thank you.

The continued sales makes it easier for me to write more online, and defend the time for more books. I can’t tell you how much I’ve appreciated the support. Hope y’all like the myths of innovation book when it’s out: I think you will :)

If you have questions about life on this end of the book, fire away.

If you’ve been reading here for awhile you know I have some questions about innovation history. Well the book I’ve been working on for the last two years has some answers.

The book is called The myths of innovation and it has 3 goals:

1) Identify the myths we have about new ideas and innovation

2) Explore why they’re popular and how they came to be

3) Use lessons from history to replace myths with knowledge

I’m taking big swings in this book: I take on meaty concepts like creativity, revolution, history and progress, telling great stories from innovations past, while delivering advice at a fast pace. It’s a shorter book than artofpm but the challenge to readers, and the value, is much greater. (But what do I know – I’m just the writer).

Over the next few weeks leading up to the book’s April release (date tba) (book is out now and a bestseller) I’ll dig in on some of these themes, shed light on the myths, and give you a preview of what’s to come. A book tour like last time (west coast and east) is in the works, and I’ll post more details as I have them.

Thanks to all of you who have commented here along the way: Its made a difference and I’m grateful.

One of the little details authors fret about is footnotes vs. endnotes. It’s a style choice: should you keep a slot at the bottom of every page for notes, or collect them all at the end of the book (or chapter)? A quick survey of 10 books from the library shows:

Endnotes: 4

Footnotes: 4

No notes(!): 2

Sure, its fair to say who cares – what is in the notes matters more than where they are, but still. Don’t you have an opinion? Many folks do and get quite passionate about it. Here are the main arguments:

Footnotes. The pros: You can quickly check the note without leaving the page, and the author can stuff funny things in there. The cons: it’s distracting if there are lots of notes and can be visually ugly.

End-notes: The pros: Saves research questions to the end and keeps pages clean. Cons: the footnotes are rarely read and if they are, it’s hard to know what the author is referring to. You also have to jump back and guess where the note came from.

I ask because my book is at that stage. If you have any bright ideas, or entertaining rants, I’d love to hear them now.

Update: Decision was made and you can read about it here.

Founders at work

Founders at work is a collection of interviews with, surprise, founders of tech-sector companies. The goal is to capture their recollections of the early days of their successful ventures, and share stories that were often overlooked.

is a collection of interviews with, surprise, founders of tech-sector companies. The goal is to capture their recollections of the early days of their successful ventures, and share stories that were often overlooked.

The interview list is first rate: founders from Hotmail, Adobe, Excite, Firefox, Yahoo! and more than 20 other well known companies are included.

The upside is that these stories read honest: there’s struggle, failure, fear, mis-steps and changes of direction, all the things often glossed over by high level mainstream interviews of success stories. If you’ve wished you could have a chat with some of these folks, you’ll be happy with this book. Livingston does a good job of staying out of the way and tries to cover similar territory with each interview (however it has the minor effect of making the book more readable in separate sitings, as the repetition of questions tires after 5 interviews in a row).

The other risk for those with dreams of entrepreneurship is that the stories come across as ordinary: there are few magic moments, radical breakthroughs, or amazing coincidences: its mostly hard work, and fantasies of what starting a company is like will fade by the 8th interview.

This book is inspiring at times: mostly because it makes the stories of these startups real. These were human beings doing these things, not omnipotent geniuses. Anyone expecting triumphant, and replicable, vision for why these folks succeed will be forced to look elsewhere, or perhaps more to the value of this book, reconsider what it takes to found a successful company.

Buy Founders At Work at Amazon.com.

The author, Jessica Livingston, is a partner at Y Combinator, a venture firm for early startups with some novel ideas on what venture firms should do.

I recently met Jonah Burke, one of the directors of the darfur foundation, to chat about innovation. I came across his project, darfurwall.org, at Ignite Seattle, a local tech-sector meetup.

I recently met Jonah Burke, one of the directors of the darfur foundation, to chat about innovation. I came across his project, darfurwall.org, at Ignite Seattle, a local tech-sector meetup.

Months ago I wrote a preechy essay about difference making: well, here’s an example of someone doing the real thing.

Not only is darfurwall.org a clever piece of design and engineering, it serves a purpose: all the money people chip in for lighting up the digital wall goes straight to helping people in need. Like a physical monument, it gives a sense of both the impact of what has happened, but also offers a way to participate. Check it out.