I’ve published six successful books and in the years it took to write each one I’ve heard every range of opinion on what makes a good book title and how important it is or isn’t. Here’s what I’ve learned, and it applies to fiction, non-fiction and even other kinds of creative works.

#1: Advice is cheap, decisions are hard

Everyone is very happy to tell you how to pick a title, and in particular, that you are doing it wrong.

A special joy comes from people telling you that your title ideas stink, yet who can’t offer a single better alternative. “Gee, thanks” you’ll say, to which they will offer “Hey, you’re the writer.” Both complaints are valid of course, but neither solves the problem.

There is plenty of good advice, but it’s rarely based on good data. Even a skim of the history of popular books or the current top 100 shows dozens of violations of any expert’s advice. Worse, often good sounding advice contradicts other good sounding advice. For example:

#2: This is all very subjective, even among experts

If we rounded up the wisest book editors and the smartest title creators and gave them a list of book titles for soon to be published books, they’d passionately disagree about which ones worked and why. And most of them would be wrong about the results (See #4).

We all suffer tremendous taste bias on titles. We assume our instincts and likes are matched by everyone. There are many kinds of taste, good and bad, which means there is an unbelievable amount of contradictory advice about titles, almost as much as there is about writing books themselves.

Insiders love to point to previously published books as examples of good titles, but that’s cheating. What would validate their expertise is a record of what they thought of the title before it was released. If you want an honest opinion from an expert ask them to tell you about books with “great” titles that failed, or books with “bad” titles that did well. There are many of both.

#3: Many titles are cliches

Most advice chases past successes. And the popular advice leads towards books that sound the same. Since this advice is well known many books aim for the same crowded bullseye. The paradox is they will say: “Your idea is a cliche, so take this advice (which will lead to a different cliche)”

Most genres have crowded namespaces with familiar patterns. Aiming here defeats some of the purpose of the title: to uniquely identify the book. If you follow too much of the advice you hear, soon you’ll be in questionable territory:

- The Art of Blah

- Transforming Foo

- Breathing for Dummies

- How to Blah and Blah

- Noun + Number of Noun

- Somebody’s something

- The Joy of <thing not generally thought of as joyful>

- The End of <Something people are afraid of ending>

- Extreme Coughing

- The <something important> playbook/guidebook/handbook

- <Invented word you pray will become a meme>

- Breakthrough Cheese

- How to <verb> <adjective> (“How to” is so common it’s abbreviated h/t)

- Short word: long long long long long subtitle filled with keywords (or see: Gladwell Book Title generator)

- Outrageous Claim: How something or other will do something or other

- The <insert number> of Sins/Secrets of Something

Remember that for every cliche there is an original idea for a book title that started it. And you can bet when that author pitched that title, they were told mostly why it wouldn’t work.

But know that cliches can be good if you time them right. They fade in and out year to year, being abused, abandoned and then suddenly rise as cool again. Depending on how many book titles you look at a day, your place, and your reader’s place in that timeline is different. What seems played out to you might be on the rise for your audience.

It can sometimes be effective to use a cliche if you’re going after an audience that hasn’t seen a book aimed that way (e.g. Confessions of a Public Speaker), since it won’t seem cliche to them, as the cliche is a shortcut to expressing the style of the book (e.g. 101 Things I learned in Architecture School).

#4: The title serves many functions

The non-book writing majority of our species has no idea how many different functions the title serves in the machinery of selling books. It will be used for any of:

- To convince someone to be interested in the book <— this is the one people think about

- The cover

- The Amazon listing

- Advertising, marketing and branding

- Any t-shirts, flyers or other promotional material

- In presentation slides

- The domain name

- In book reviews (and in the title of book review blog posts)

- The thing the author will say 5000 times in interviews, lectures, radio and TV appearances (should they be so lucky)

- As a one line bio on TV or for magazine articles

- As the brand name for other ventures (courses, conferences)

- The thing readers (hopefully) will say to their friends 5000 times

Each of these has slightly different requirements and you can’t nail them all at the same time. Most are improved with brevity.

#5: Titles aren’t predictive of sales

Two facts about books:

- There are many great books with dubious titles, and awful books with fantastic titles

- Many popular books suck, and many awesome books are unpopular

Book publishing is not a meritocracy. Even if it were, dozens of decisions influence the outcome. There are many reasons books become popular, or not. Some books become popular in spite of their author’s choices. Other books do everything most things right, and never do very well.

One factor in the overstating of title importance is insecurity and ego. At the time an author and a publisher are deciding on the title they are both at their greatest emotional insecurity: the book is not finished and not released. Their fears only puts more pressure on the decision, not less. Another reason is people other than the writer want to make their mark on the project and the title is the single most prized sentence in the entire book writing enterprise, and it’s easy to express opinions about it (whereas opinions on the text of the book itself requires hours of investment). Many books are chosen by editorial committee and you can guess which ones they are.

Titles of course have an impact on a book’s success. Often its all a potential buyer ever gets to see, and if they can draw interest the book crosses its first of many hurdles in the improbable struggle of getting noticed. But titles only help so much. Most people hear about books the same way they hear about new bands. Or new people to meet. A friend or trusted source tells them it was good and it was called <NAME HERE>. The title at that point serves as a moniker. It’s the thing you need to remember to get the thing you want to get and little more.

#6. We feel differently after we read the books

Many titles are meaningless until after you read them. Consider the day any of these were first published: The Mythical Man Month, Catcher in The Rye, Catch-22, To Kill A Mockingbird, Moby Dick, Eats, Shoots, and Leaves, Eat Pray Love. After these books were successful of course the titles seem great. But you wouldn’t have said that before the book came out. Or go further and ask about REM or Led Zeppelin or RUN DMC. What? Names for things sometimes are just names for things. They let us refer to a thing, and that’s it. If we love the thing we eventually love the name. You didn’t marry your spouse purely because of their name, right? Or what city you live in? Or what company you work for?

It’s entertaining to consider the names of many publishers: HarperCollins, Simon and Schuster, MacMillan. These names mean nothing as names since they are the actual names of their founders. What rule of naming was followed here? Sure, companies are different from books, and these companies have done very well. But consider Random House, which was named because the founders wanted to publish “a few books on the side at random“? None of them exemplify a strategy based on the importance of a name choice in the success of a venture.

#7: What really matters

Of all the advice I’ve read, been given, had thrown at me, or pulled out of of more experienced authors, here’s the core of what matters:

- Short. Fits anywhere. Easy to type, write, make into a URL, tweet and text. Unless you are Fionna Apple.

- Memorable. The more specific, original and short the title, the easier it is to remember. Or write down. Or type into amazon. A title can be both cryptic and easy to recall: Life of Pi means almost nothing to someone who hasn’t read the book. But it’s just 3 one syllable words.

- Provocative. One way to be memorable is to be provocative. To achieve this likely means dividing your audience: provided half of that division is very interested, it’s a win. It’s better to split a crowd than to bore everyone. Many books make a provocative promise that’s impossible to deliver on. You need to decide how close to an infomercial you’re willing to be.

- Easy and fast to say. At parties, on TV, on Radio, the name should be easy to say and enunciate. The fewer the syllables the better.

- Author wont get sick of saying it 1000 times. Anyone selling the book, including the author, will say the book title thousands of times. Consider what you will think of the title the 5000th time or five years from now. You want something you’ll be excited about each and every time you say it.

- Matches the soul of the book. Only people who have read the book can help here. Many novels make the title pay off after you’ve read it and in some ways make the title more potent than other kinds of titles. Organic titles, meaning titles pulled from something in the book itself (a story, a term, a name, such as The Perfect Storm), can work well.

#8: What to do: Make a big list

The best solution to subjective creative challenges with cheap materials (e.g. words) is to make a big list of candidates. As big as possible. Include anything you like, including cliches. Take your time, over days and weeks. Show the list to lots of people with the goal of making the list bigger. Often there are hybrids and variants that you’ll discover only by growing your list.

When you’ve made a big list and don’t find many new ones, make a specific list of your criteria (see above). Then slowly work to winnow down the list. Here’s good advice on looking at competitive titles and list creation.

#9: Use modern tools like polling and A/B Testing

When you have a small list of titles you like, get some data. Tim Ferris, Eric Reis and others have graciously popularized the methods they used for applying A/B testing methods (Like Pick-Fu) for picking book titles. From experiments with their websites, to using sample google ads for book title candidates to compare how people respond. This is excellent. Data should inform opinions. It can’t answer every question but it can verify or disprove assumptions in ways no amount of debate can.

However, A/B testing can never generate the candidates for you. It also never tells you how to break ties. And it can’t tell you anything about how well the title matches the book. You might find a title that gets a fantastic response, but isn’t a good match for the book you wrote.

#10: Remember A title is just a sentence

If you’re a writer you will write hundreds of thousands of sentences in your career. Only your name is going on the book: put some confidence in your own judgement.

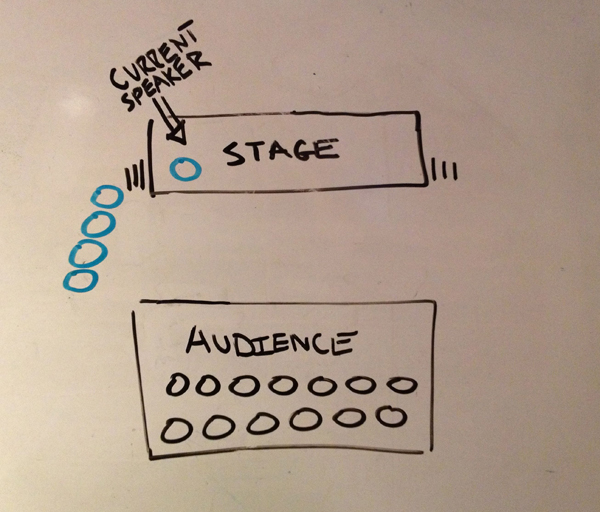

Last week I was on an expert panel, giving feedback to final project presentations at the

Last week I was on an expert panel, giving feedback to final project presentations at the