As promised, here are answers to all of the questions from Yesterday’s Webcast on Innovation.

mFree chapters for The Myths of Innovation are here, or go crazy and just buy the book, 70+ amazon reviewers can’t be wrong.

The recording recording of the entire webcast can be found here (ASX)

Q: You talk in the book about innovation not happening in a vacuum. What is your take on user centered design and involving users in the innovation process?

If you made a friend a meal, wouldn’t you ask them what food they like? What allergies they have? That’s a (simple) kind of user centered design. No maker of things can do well if they don’t study the people they are making things for. The trap is not to involve them too much. Most users will only have feedback on what already exists, and if you only follow ideas that comes from users, you’re unlikely to break new ground.

Q: When a new idea looks strange, how do you tell a great one from stupid? Try them all and see what works, or select one and push it as far as you can?

You can’t tell just by looking. You have to put ideas into action. Make a prototype. See what happens when the idea meets the world. Sometimes keeping a strange idea around and poking at it now and then is simply good exercise. It keeps your creative muscles working, so when a weird idea that has the potential to be great comes along, you’ll be patient and persistent enough to discover its potential.

Q: What was the full name of the razor principle?

Occam’s Razor. You can read all about it.

Q: What do you think are the best examples of the maverick principle: that there is a group-think conducive to incremental innovation but not significant positive change, but that outsiders, free of such group-think, are the more likely source of outstanding innovation?

I think incremental innovation is one of those terms that should go away. Just call it work, progress, improvement. The phrase “incremental innovation” is about as silly as “gradual explosion” or “partial death”. Either something is big or its small. If you’re not sure, call it small. Be humble, as being humble lowers the odds your ego will get in your way.

Democracy is not a system designed for change. Individuals will always be the drivers of change in the sense that if they are working alone, they have fewer people to convince of their ideas. If they need 10 people in a room to agree to follow an idea, progress is very hard. This explains why so many big ideas are developed by entrepreneurs. They are taking on the burdens of risk in exchange for more autonomy.

Q: Seems to us as a small group of clean energy inventors, that when the nature of our innovations inspires (or even dictates) a business model innovation as well, it gets far more difficult to push the process and recruit support. Any thoughts? Really looking forward to your book, although we’ve already created something we’re trying to commercialize as a non-profit.

Support is always hard. Chapter 4 of the book is all about the many horror stories of lack of support that happened before the “overnight successes” of many famous ideas. One of my favorites is the story of Chester Carlson, who, after enduring many hardships and much isolation, would go on to invent the copy machine.

Business model innovations are macro: they take time for people to understand, and people will need more faith to follow. All I can say is, be glad your ideas don’t require political system innovations, or metaphysical innovations, as those are even harder to get support for.

Q: What are some of the best online tools you’ve found to help people collaborate and give them a platform for experimentation?

I’ll probably sound like a jerk for this one, but if a person can’t collaborate on the web today, I don’t think lack of tools are the problem. The web, and software in general provide one of the cheapest formats ever in history for developing ideas and sharing them with others. For a few hundred dollars you can build a website, sell a product, and on the day you launch it will be available to anyone on the entire planet. Edison, Newton, Tesla would all have given their right arm for a platform of experimentation as powerful as what you have right in front of you.

Q: Suggestion on how to become at convincing people your idea rocks? books, how to practice?

Start with my essay, How to pitch an idea.

Q: do you have resourcse that allow development beign able to persuade people

That’s not a question, so in response, this will not be an answer.

Q: please show the simple plan slide again, the four points of the simple plan

Sure. The slide said, to increase goodness (when teams are not creative):

- Make the team smaller

- Give it more authority

- Increase trust and cover fire

- Choose adventurous people

Q: People make a distinction between innovation and invention. Can you share your thoughts on this?

Definitions are funny. You can find many different ones for any word, and people who argue for hours about this sort of thing are falling into the talk is cheap trap. You do not need to have a name for something in order to do it.

But in this case I’ve heard a useful distinction. Invention is the item itself. If I invent a better web browser, but only show it to my dog Max, it stays an invention. But if I make it into a product, and it gets adopted, and changes the world in some way, it’s an innovation. This definition of innovation is based on the effect, and the word invention is limited to the thing that (possibly) creates the effect.

Q: Love the inspiration around Innovation but need advice on how to navigate the red tape/resistance by Corporate America encountered when trying to present innovative ideas.

The book is largely designed for you, so start there. In short: pick your company, your role and your manager. Some industries are more focused on change than others (say, software companies vs. your local bank). Then, consider your job. A janitor at a bank is not being hired for creativity, so his grand ideas won’t be welcome. But if gets a job as a product designer, or a lead developer on a website, people’s expectations for his creative contributions will be larger. Lastly, some bosses are much better than others at creative environments for creative people to thrive. Seek them out. They’re hard to find, but they’re there. A great manager in a mediocre company might be a happier and more productive place, than working for a mediocre manager in a great company.

Q: It seems like it’s often the case that the person/company who generates a truly new idea/technique/process/design is not ultimately the same person/company that benefits finacially or gets the recognition. Why is this the case? Has access to internet technology changed this?

In race car driving, the car in 2nd place can draft behind the lead car, using the lead car as a shield against the wind. Same is true in the business world. Whoever is first has the burden of proving a new idea. Once it’s proven to some degree, whoever comes second has, in a sense, less work to do. The barriers of entry are lower. Also, entrepreneurs have less resources than Fortune 500 companies. A late comer can out market and advertise whoever was first.

Q: Is the book on listening CD?

I don’t know what a listening CD is (aren’t all CDs for listening? I mean is there a chewing CD somewhere? A toasting CD?). A recording of the webcast is online here (ASX).

Q: How do you best pursuade people who are antagonistic towards something new?

Understand their goals, and think about how your idea helps do what they’re trying to do. Also read How to pitch an idea.

Q: How can we find worthwhile problems to solve in the first place?

How about poverty, crime, war. Those are all worthwhile. In your industry or company, simply find smart people who are complaining and start there.

Q: Fantastic presentation!!

Thanks! Not a question, but in this case I don’t mind! Hopefully soon I’ll stop using exclamation points!

Q: Every once in while you hear people talk about planning innovation. What do you say to them?

I say hooey. They are planning product development or how they’re going to develop ideas, but unless they are going to bet their salary that the result will be a great idea that changes the world, I’d suggest they use less inflated language.

That’s it. If you were there and have more questions, leave a comment. Otherwise, free chapters for The Myths of Innovation are here, or go crazy and just buy the book, 70+ amazon reviewers can’t be wrong.

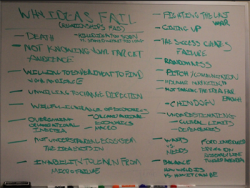

I ran a session at

I ran a session at  The range of sessions is entirely self generated and that’s part of the fun. There is a strong tech bias, but many of the folks here have non-profit or cultural ambitions, and that’s reflected in the sessions they choose to put on. And since the board has a huge number of slots, people come up with ideas for sessions late in the day, often as a result of a conversation that took place in a previous session.

The range of sessions is entirely self generated and that’s part of the fun. There is a strong tech bias, but many of the folks here have non-profit or cultural ambitions, and that’s reflected in the sessions they choose to put on. And since the board has a huge number of slots, people come up with ideas for sessions late in the day, often as a result of a conversation that took place in a previous session. The Productive Geek: The irony of a session like this is the people there are amazingly productive, but feel unproductive, leading to the suggestion the problem is not technological but psychological (e.g. we need therapy, not technology). I heard a few people mention time off as a boon to productivity (first day back after a 3 day email/information fast is very productive). I suggested productivity is measured in quantity, rather than quality and that’s a large part of the problem.

The Productive Geek: The irony of a session like this is the people there are amazingly productive, but feel unproductive, leading to the suggestion the problem is not technological but psychological (e.g. we need therapy, not technology). I heard a few people mention time off as a boon to productivity (first day back after a 3 day email/information fast is very productive). I suggested productivity is measured in quantity, rather than quality and that’s a large part of the problem.