5 lost truths on Innovation – My speech at The Economist

Below is a video and transcript of a short speech I gave at the The Economist’s Ideas Economy event at UC Berkeley on the 5 most important and most overlooked notions about innovation that managers and leaders often ignore at their peril.

Speech Transcript

Today I make a living as a writer of books and I talk about ideas from those books. But my first career was leading teams of people. I worked on Internet Explorer in the early days of the web, on version 1.0 to 5.0 and my job was to be a practitioner in many of the things we’ve been talking about so far at this event. My job most of those years was to lead a team of designers and engineers in making new things. We did research, we made prototypes, we engineered those prototypes into products, and we released them into the world. We shipped a new version about every 3 or 4 months, and the work we did was relatively new in the world, or at least new for Microsoft.

I was very young when I had this job, and I took it upon myself to learn as much as I could about what had come before my time. I studied what legends like Edison, Einstein, DaVinci, Ford and others had done. And not what we thought they did, but the actual histories, and first person accounts. I wanted to understand what they thought of their work at the time, rather than what we, much later, project retroactively into it. And when I quit my job in 2003 to write books, I knew I wanted to write a book about all the things I’d learned about creativity and invention, from personal experience and history, that I wished someone had told me when I started. There is so much misinformation in creative thinking and stories of invention. The book, The Myths of Innovation, is a bestseller and explains much of my success so far, and it’s what I’m going to talk about today.

I’m an Occam’s razor kind of guy. And Occam’s razor is the notion that if you have two theories for explaining something, the simpler one is probably right. And when it comes to innovation this is the lens I use. And with that in mind I have a few observations for you.

First, most teams don’t work. They don’t trust each other. They are not led in a way that creates a culture where people feel trust. Think of most of your peers – how many do you trust? How many would you trust with a special, dangerous, or brilliant idea? I’d say, based on my experiences at many organizations, only one of every three teams, in all of the universe, has a culture of trust. Without trust, there is no collaboration. Without trust, ideas do not go anywhere even if someone finds the courage to mention them at all.

Second, most managers/leaders are risk averse. This isn’t their fault, as most people are risk averse. We have evolved to survive and that typically means being conservative and protecting the status quo. Looking at you in the audience I can tell you I don’t see anyone who has dressed innovatively, or is behaving creatively right now. You are all sitting in nice little rows, dressed in nice, but conservative business attire. This is not a surprise. Most people, most of the time, behave much as you are right now, certainly if anything involving work is concerned.

But without the ability to take risks, innovation and progress can not happen. Even if you have a good idea, to bring it into the world is risky. Even if you can develop that idea into a good product, you must release it into the world and there are a hundred unfair reasons outside of your control that will change how that ideas is perceived and whether it will succeed or fail. The history of innovation and progress of all kinds is made up mostly of failures for this reason, and any great successful revolution you hear of was almost certainly proposed and rejected many times before it found any support in the world at all. You’ll find very few big ideas that were adopted with immediate open arms and unconditional love by those in power.We know this, which is why we often keep our best ideas to ourselves. They are much safer there.

Without teams of trust and good leaders who take risks innovation rarely happens. You can have all the budget in the world, and resources, and gadgets, and theories and S-curves and it won’t matter at all. Occam’s razor suggests the main barrier to innovation are simple cultural things we overlook because we like to believe we’re so advanced. But mostly, we’re not.

Third, we need to get past our obsession with epiphany. You won’t find any flash of insight in history that wasn’t followed, or proceeded, by years of hard work. Ideas are easy. They are cheap. Any creativity book or course will help you find more ideas. What’s rare is the willingness to bet you reputation, career, or finances on your ideas. To commit fully to pursuing them. Ideas are abstractions. Executing and manifesting an idea in the world is something else entirely as there are constraints, political, financial, and technical that the ideas we keep locked up in our minds never have to wrestle with. And this distinction is something no theory or book or degree can ever grant you. Conviction, like trust and willingness to take risks, is exceptionally rare. Part of the reason so much of innovation is driven by entrepreneurs and independents is that they are fully committed to their own ideas in ways most working people, including executives, are not.

Forth, I need to talk about words. I’m a writer and a speaker, so words are my trade. But words are important, and possibly dangerous, for everyone. A fancy word I want to share is the word reification. Reification is the confusion between the word for something and the thing itself. The word innovation is not itself an innovation. Words are cheap. You can put the word innovation on the back of a box, or in an advertisement, or even in the name of your company, but that does not make it so. Words like radical, game-changing, breakthrough, and disruptive are similarly used to suggest something in lieu of actually being it. You can say innovative as many times as you want, but it won’t make you an innovator, nor make inventions, patents or profits magically appear in your hands.

Fifth and last, I know from my studies if you are in the room when something that is later on called an innovation is being made, the language is always much simpler. Words like problem, solution, goal, experiment, and prototype, simple workmanlike words are the language you’ll hear. And whenever I’m invited somewhere to talk about innovation, or to help an organization, and I’m in a meeting where any of the fancy words are used I always raise my hand and ask: What do you mean by innovation? And most of the time they have to stop and think. They don’t really know what they mean.

And if the person speaking doesn’t know what they mean, odds are good no one else in the room knows what they mean either. Without good communication trust is unlikely, if not impossible. Typically people mean one of five things when they say innovation: 1. We want to do something new 2. We want something new and good 3. We want something new and good and profitable 4. We want to be more aggressive and work faster 5. We just want to be perceived as being innovative. Any of these simple declarations are easy to understand. Odds of innovation happening go up when this kind of language pervades a culture and history suggests clear language is one of the tools great thinkers, creators and innovators have always used.

[At the event itself the word innovation was used 181 times. That was almost 30 times an hour. I’ll leave it to you whether we’d have gotten more value from the day if the word was used more, or less, or if it made no difference at all.]

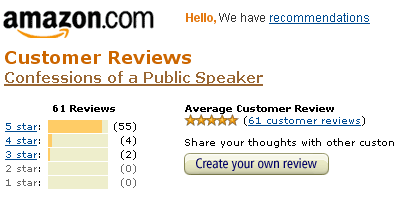

Lastly, I’d like to offer you an invitation. First, thanks to The Economist for inviting me to share a stage with Jared Diamond and Robert Reich. But also, for allowing me to give you a gift. There are 200 copies of my bestseller, the Myths of Innovation, waiting for you out in the hall. Thinking of Occam razor, I’d love to know if you see a simpler way to understand how innovation happens than the one I offer in the book, and to let me know about it. And by the same token, if the book helps simplify how you think about what you do, or hope to achieve, I’d like to hear about that too. Thanks for listening.

You can also watch the talk here.

Well here we are. It’s post 1000! Surprised to have written so much here. Thanks for reading, linking, and commenting, as that’s a huge motivator for my prolificity.

Well here we are. It’s post 1000! Surprised to have written so much here. Thanks for reading, linking, and commenting, as that’s a huge motivator for my prolificity.