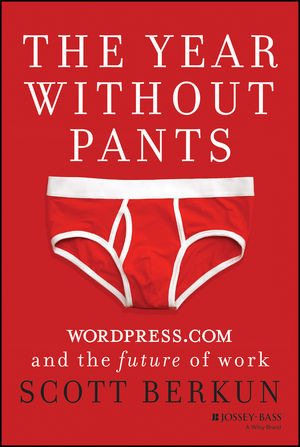

Thanks to everyone who has tweeted, Facebooked and blogged so far in support of The Year Without Pants: WordPress.com & The Future of Work, now an Amazon.com best book of 2013. There have been more than 50 reviews in the media and 139 Amazon reviews so far. We’re off to a good start. If I missed one, yours or someone else’s, leave a comment and I’ll add it in. Here’s the list of reviews & mentions to date. I’ll update over time:

Tweets

Facebook:

Early endorsements:

“The Year Without Pants is one the most original and important books about what work is really like, and what it takes to do it well, that has ever been written.”

—Robert Sutton, professor, Stanford University, and author, New York Times bestsellers The No Asshole Rule and Good Boss, Bad Boss

“WordPress.com has discovered a better way to work, and The Year Without Pants allows the reader to learn from the organization’s fun and entertaining story.”

—Tony Hsieh, author, New York Times best seller Delivering Happiness, and CEO, Zappos.com, Inc.

“The underlying concept—an ‘expert’ putting himself on the line as an employee—is just fantastic. And then the book gets better from there! I wish I had the balls to do this.”

—Guy Kawasaki, author, APE: Author, Publisher, Entrepreneur, and former chief evangelist, Apple

“If you want to think differently about entrepreneurship, management, or life in general, read this book.”

—Tim Ferriss, author, New York Times best seller The 4-Hour Workweek

“With humor and heart, Scott has written a letter from the future about a new kind of workplace that wasn’t possible before the internet. His insights will make you laugh, think, and ask all the right questions about your own company’s culture.”

—Gina Trapani, founding editor, Lifehacker

“Some say the world of work is changing, but they’re wrong. The world has already changed! Read The Year Without Pants to catch up.”

—Chris Guillebeau, author, New York Times best seller The $100 Startup

“Most talk of the future of work is just speculation, but Berkun has actually worked there. The Year Without Pants is a brilliant, honest, and funny insider’s story of life at a great company.”

—Eric Ries, author, New York Times best seller The Lean Startup

“The Year Without Pants is a highly unusual business book, full of ideas and lessons for a business of any size, but a truly insightful and entertaining read as well. Scott Berkun’s willingness to take us behind the scenes of WordPress.com uncovers some of the tenets of a great company: transparency, team work, hard work, talent, and fun, to name a few. We hear about new ways of working and startups, but we rarely get to see up close the magic that can occur when we truly tend, day in and day out, to building something bigger than ourselves.”

—Charlene Li, author, Open Leadership, founder, Altimeter Group

“ Once you’ve seen how WordPress.com does things, you’ll find yourself asking why your company works the way it does.”

—Tom Standage, editor, The Economist

“Berkun smashes the stereotypes and teaches a course on happiness, team culture and innovation”

—Alla Gringaus, web technology fellow, Time, Inc.

“The future of work is distributed. Automattic wrote the script. Time for rest of us to read it.”

– Om Malik, founder, GigaOM

You’ll be surprised, shocked, delighted, thrilled and inspired by how WordPress.com gets work done. I was!

– Joe Belfiore, Corporate Vice President, Microsoft