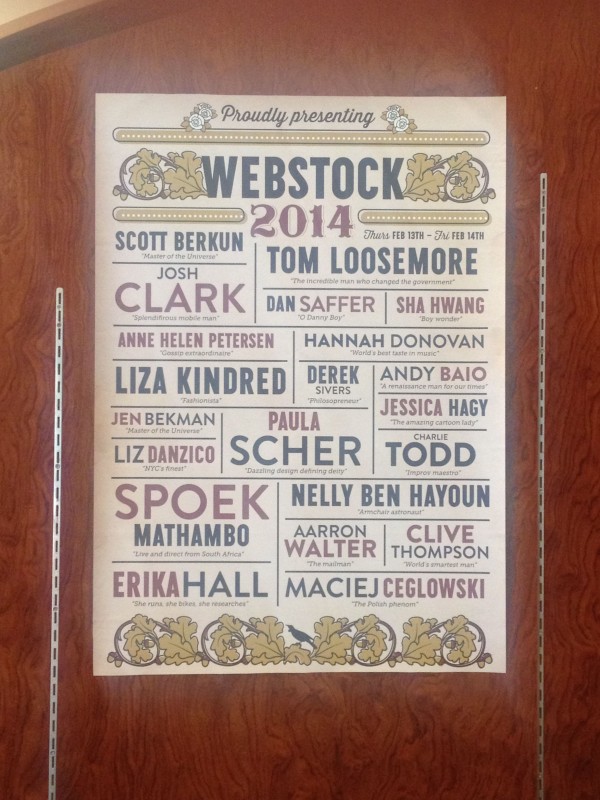

I did an entire presentation on How To Overcome Tough Presentation Situations, based on Confessions of A Public Speaker. If you’re looking for the raw list of situations and remedies, they’re in the slides below.

Below is the Q&A that happened after the presentation.

Q: Ok, Scott, am I the first to ask? Are you wearing any pants?

Yes!

Q: How one can handle differently experienced crowds? Like half expect detailed technical explanations and the others just want an intro into the topic.

This should be solved by your title and description. If you don’t want novices, the title should be “Extreme ultimate advanced cake baking.” If you only want novices, title it “How to make a cake for the first time.” The organizer should be trying to help you avoid this situation too.

The first item on the checklist is to ask about demographics for your audience before you work on your presentation.

If you do somehow end up in a room with a mixed audience, find out how mixed it is. Poll them: “How many of you have never done X? Done it 5 times? More than 5 times?” And then at least you know who you’re talking to and can adjust the points you make accordingly.

The best stories and insight cut across expertise. Listen to This American Life, The Moth or RadioLab and pay attention how they tell stories about seemingly basic topics but make them interesting to almost anyone.

Q: Should you prepare shorter versions?

If you prepare using the method offered in Chapter 5 of Confessions of A Public Speaker, you’ll always have a list of key points you can fall back on no matter what happens. Also see how to present without slides.

Q: Any tips for presenting to youths? E.g., regarding careers in computer science for a career day? This is a particularly tough audience for me.

It’s harder to speak to people who didn’t choose to come. Always think hard about why they might be interested and start there. In your case, start by telling them how much money they can make or the amazing things they didn’t know were made by computer scientists (video games, the apps on the phones in their pockets, etc.). There is always a way to focus on the audiences perspective – it’s just a question of working to find it. You could also talk one on one with a student and get a personal perspective on what they would advise, or what feedback they have for you for the next time you give the talk.

Q: What if the people staring at their smartphones are the members of the Board of Directors, meanwhile your are presenting a project for their approval?

If you think there is a zero % chance you’ll get the approval if they stare at their phones, ask them not to. Every organization has a different culture and different rules for etiquette. But if my job was to get an approval and I was failing I’d take the risk breaking of etiquette.

Q: How do you skip several slides gracefully?

You can’t. Some people complain when I skip slides but it’s far better than the alternative (wasting their time covering something I no longer feel I need). I skip slides for their benefit, not mine. Either I already told a story or a point seems less relevant given what I’ve learned about the audience. Maybe I’m running out of time so I’m reprioritizing. Often I’ll just say “I already covered this” or “we don’t need this now so I’m moving ahead”

However if you’re doing a lot of slide shuffling you didn’t practice enough or didn’t practice with a timer.

Q. What if you get to Q&A sooner, but there aren’t any questions?

Everyone goes to get a beer! Seriously, if there are no questions it means all questions were answered or the audience isn’t interested. In both cases it’s time to go.

Some cultures, Asia and Northern Europe in particular, are more conservative about engaging with speakers and it can take more effort from the host or the speaker to get someone to break the ice. Some cultures rarely clap or respond to performers at all. It’s always good to ask a host what the audiences are usually like.

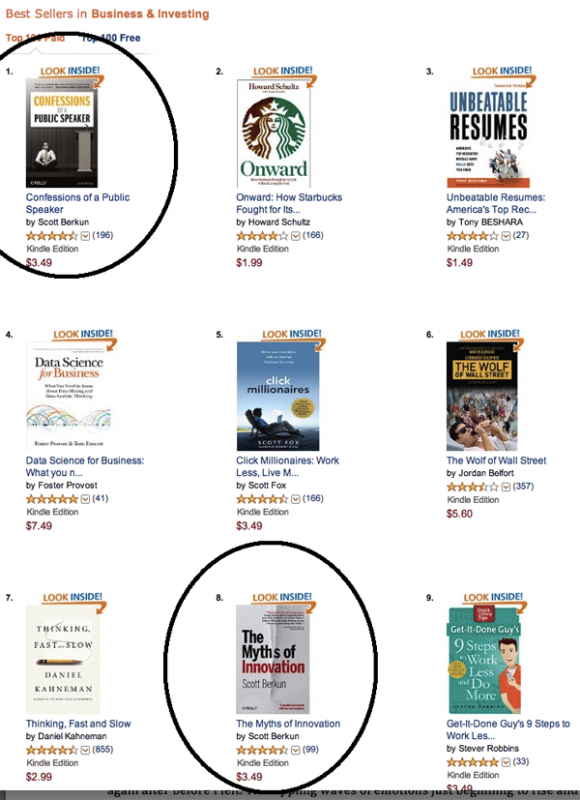

I like questions so I usually have a stack of books to give away and offer them to people who ask questions. I’ll at least have one copy to give to the first asker since that’s the hardest one to get.

Q. Two questions: I attended a Q & A with an author who has a very devoted following. One of the attendees asked her “Will you be my mentor?” What followed was an awkward conversation that threw the rest of the Q & A off. How would you have handled it?

I’d have been polite and made some kind of joke and then moved on to the next question. There is no obligation for a speaker to answer or respond to everything.

There’s never harm in moving along. You can always choose to return to a question later if you decide, later on, it’s worth more time.

Q: How can you manage switching media (e.g. slides and some live demo or a video file) – I tend to prepare “backup” slides in case demo failure. Any other tips for such a situation?

My advice on demos is here: how to give a great demo.

Keynote handles media better than most other tools I’ve seen, but it’s always risky. Projectors are finicky beasts. Backup in slides is a great idea. I also never trust wifi or any network for anything: if I don’t have a local copy of something I won’t depend on it working.

Q. Do you have good reading tips or similar on preparing the presentation itself. It’s a creative process that I struggle with sometimes. How to tell the right story, what should i keep in the presentation and what should be removed and so on.

Chapter 5 in Confessions of A Public Speaker the simplest and strongest process I know for developing material. Most people simply fail to practice. You can’t know how all of the stories and facts will fit together until you try it. If you were doing a play you’d rehearse dozens of times. For a presentation you should do a dry run early in the process so you don’t get distracted by slides and other props.

Q: How do you handle hecklers?

Hecklers are incredibly rare. I’ve given hundreds of lectures and have only been heckled a few times. Unless you are a standup comedian, very few people feel comfortable, or drunk enough, to challenge you. Always know that you are the person with the microphone and therefore all of the power as you can talk over anyone in the room if you choose to. Also realize that everyone came there to see you, not the heckler. The best thing to do is to keep your cool, politely dismiss the heckler (“please hold questions until the end. Thank you”) and continue. If they persist, remind them again and continue. If they refuse, look to your host to help control the room.

Q: What if you have no microphone and/or the heckler is a VIP?

They are not a VIP for the talk if they are not on stage. The rules are the same. If they interrupt me the audience expects me to stay in charge of the room. Heckling is very rare. If the VIP were my boss or something like that I’d still ask them, politely, to hold questions and comments to the end. They’d have to break that request in front of dozens of other people which even the most arrogant executive is unlikely to have the nerve to do.

Q: What if you laptop explodes? Or more generally, how do you prepare for an “impromptu” talk (ie, a talk you are asked to do 30 minutes from now).

My advice is basically the same as how to present without slides but with a simpler structure. I’d consider my audience and the 5 or 6 questions I think they want me to answer, or the major points I want to make. If I’m knowledgable on the subject I should be able to talk on each of those without any planning for a few minutes each. If you’re not a brain surgeon and you’re being asked to talk about brain surgery 30 minutes from now, you should question the sanity of the person asking you to speak.

Q: Would you recommend to follow training like improvisation theatre classes?

Improv classes are great fun and teach you many useful lessons. Here’s Why I Recommend Taking Improv. I found it particularly useful for dealing with many of the situations discussed in the talk. Through playing games you learn how to pay attention, how to listen better and how to, well, improvise. I became dramatically better at Q&A after taking a series of improv classes.

Q: What do you think of PechaKucha format? Any tips for doing this properly?

I’m one of the organizers of Ignite Seattle, a format similar to PechaKucha. Here’s my talk, in the Ignite format, about How and Why To Give An Ignite Talk. Also see this How To Give A Great Ignite Talk. I wrote this article about the history of short form speaking for Forbes.

Q: How do you make a presentation about Project Management without sounding like you’re telling people how to do their jobs? (i.e. you want some improvement in the company but don’t want to offend etc).

Presentations aren’t the best way to make change happen. No one is obligated to listen or to do anything even if they agree.

I’d work the other way. Who is doing great work in project management, inside the company or outside? What examples will inspire people to consider working differently? A talk is a great way to expose people to different ways of thinking about their work and get them interested in learning more.

I’d also much rather give a presentation highlighting a team or project that is doing some of the “right” things and use them as an example, rather than simply tell an entire company they’re doing something wrong.

Q: I talk fast, like Jesse Eisenberg fast. Is it best to prepare more material so the talk doesn’t go by too fast or try to really slow down, which feels a little unnatural?

Talkingfastisverybadbecauseitmakespeoplesbrainshurtjustlikethisdoes.

First rule of speaking: don’t make people’s brain hurt.

Speaking fast is a simple problem to solve. It’s not fun, but it’s straightforward. Grab a favorite speech or a talk of your own and set a timer. Practice doing the talk in 10 minutes. Then practice, with the same talk and same number of words, doing it in 12 minutes. Then 15 minutes. Pace is a habit and it’s easy to learn to change. You’ll learn it’s ok to pause and breathe between sentences (and words!).

Q: what techniques do you recommend to prevent “filler sounds” (ah, um, etc…) when speaking?

Similar to the above. Grab a favorite speech or a presentation of your own. Get a timer. Start timing. Whenever you use a filler sound, start over. At first you’ll only get a minute or two in, but as the repetition drives you crazy you’ll slowly learn to control it and eventually turn it off completely.

Q: Tips for feeling comfortable away from a podium?

You stand behind a lectern, and on top of a podium.

The way to feel comfortable with anything is to practice it. Go into an empty conference room and give your talk. Try moving around. Try standing to the side of the lectern. Try try try. You can’t be comfortable with something physical just by thinking about it. You have to do it.

Q: Any suggestions for preparing to speak on a Webcast? Hard to speak without audience feedback.

It’s the P word again. PRACTICE. When you practice you are giving your talk at full voice and volume to an empty room. As weird as this is it helps make the weirdness of a webcast familiar. Good webcast tools give you a chatroom and the ability to poll an audience. Use them. Take a break every ten minutes to jump into the chat room for 5 minutes and answer questions.

Q: As an instructional designer who is required to prepare material to be delivered by others, can you offer tips for the best way to get them to engage with this material?

No one can feel engaged presenting someone else’s material. If you want them engaged involve them in the process of making the material. Or provide options for them about which stories to tell or exercises to use. Then at least they have some decisions and control over how the material is delivered.

Q: What are the important differences between delivering lectures versus giving speeches?

Speeches are rare these days unless you’re a politician. A speech typically means you’re formally addressing a large crowd without slides or other materials (e.g. commencement speech). A lecture typically means the goal is to teach something, but it’s far less formally defined.

The best way to think about all of this stuff is the audience. They don’t care about forms or whether you’re doing a lecture, or a talk, or a presentation. They care about getting what the came for. Information? Inspiration? A story? A lesson? If they get what they came for they won’t complain about whether you used slides or didn’t, or whether it was 10 minutes long or an hour.

Q: Do you prepare multiple versions of a presentation to tailor the talk to the audience on the fly?

Depends. If I’m asked to give a basic talk about one of my books I’ll often change specific stories or facts to best match the audience but keep the core structure of the talk the same. There is no shame in reusing a talk. If you’ve done a talk many times it’s probably far more polished than any new talk you could make. As long as it addresses and engages the audience how old the talk is is irrelevant.

Q. How much do you move around when you are presenting? Importance of body language?

Your voice matters more than your body or your slides. Body language isn’t anywhere near as important as people think (except the body language consultants). The single best piece of advice I give people is to be loud. To be loud you have to stand up straight and make eye contact. Those two things alone change your body language and your attitude.

Everyone is different. Some people are comfortable moving, others aren’t. What matters is that what you do helps you and helps the audience. If you pace quickly you’ll make everyone nervous. If you hide behind the lectern, you’ll be harder to hear. The only way to get comfortable moving is to practice and to speak enough that you can try different things.