Finalist in the Amtrak Writers in Residency Program

I learned today I’m a finalist in Amtrak’s Writer’s in Residency program. Of over 16,000 applicants 124 semi-finalists were selected and the 24 finalists were announced this morning.

The Amtrak website is getting hammered so I reposted the list of finalists here. Congratulations to everyone.

MEET THE 24 WRITERS SELECTED FOR THE AMTRAK RESIDENCY PROGRAM

Amtrak is excited to announce the selection of 24 members of the literary community as the first group of writers to participate in the #AmtrakResidency program. Over the next year, they will work on writing projects of their choice in the unique workspace of a long-distance train. The 24 residents offer a diverse representation of the writing community and hail from across the country. Meet our residents below:

Ksenia Anske

Ksenia Anske is a Seattle based fantasy writer, entrepreneur and social media marketer. She was born in Russia and came to the U.S. in 1998, never imagining a career in writing. In 2009, she was named one of the 100 Top Women in Seattle Tech and has published several short stories and novels, including Rosehead and the Siren Suicides Trilogy.

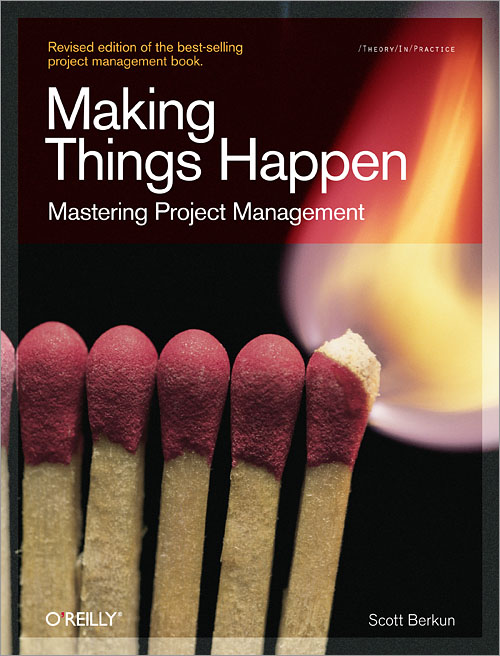

Scott Berkun

Scott Berkun is an author and speaker whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Forbes, The Wall Street Journal, and The Economist, among others. He has taught at the University of Washington and was a co-host of CNBC’s The Business of Innovation show. His latest book, The Year Without Pants: WordPress.com & The Future of Work released in Sept 2013 and was named an Amazon.com best book of the year. He writes regularly on his popular blog and tweets at @berkun.

Jennifer Boylan

Jennifer Boylan is an author and the inaugural Anna Quindlen Writer in Residence at Barnard College of Columbia University. She also serves as the national co-chair of the Board of Directors of GLAAD, the media advocacy group for LGBT people worldwide. She is a Contributing Opinion Writer for The New York Times, and also serves on the Board of Trustees of the Kinsey Institute for Research on Sex, Gender, and Reproduction. Her 2003 memoir, She’s Not There: a Life in Two Genders was the first bestselling work by a transgender American.

Craig Calcaterra

Craig Calcaterra writes for the HardballTalk baseball blog at NBC Sports.com. From March 2007 until December 2009, he wrote ShysterBall, a baseball blog. Craig also spent eleven years as a business litigation and constitutional law attorney.

Jen CarlsonJen Carlson is the Deputy Editor of Gothamist, a website she has been a part of since 2004. Her writing has also appeared on Jezebel, Deadspin, and back when she attended way too many concerts, she had her own music column in The Villager. She can also make anything out of one head of cauliflower… including pizza.

Farai Chideya

Farai Chideya is an award-winning author, journalist, and Distinguished Writer in Residence at New York University’s journalism institute. She has written four nonfictions books: Innovating Women: The Changing Face of Technology; Trust: Reaching the 100 Million Missing Voters; The Color of Our Future; and Don’t Believe the Hype: Fighting Cultural Misinformation About African Americans, plus a novel, Kiss the Sky. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature from Harvard College and currently resides in New York City.

Anna Davies

Anna Davies is a writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, New York, Glamour, Cosmo, Women’s Health, Men’s Health, salon.com, refinery29.com and others. She’s ghostwritten ten bestselling young adult novels for Alloy Entertainment and has written three young adult novels under her own name—Wrecked (Simon & Schuster), Identity Theft, and Followers. (Scholastic) Anna has spent the last year backpacking around the world, and is thrilled to be settling back in Brooklyn in October—and can’t wait for her #amtrakresidency adventure.

Korey Garibaldi

Korey Garibaldi is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at the University of Chicago. His dissertation research focuses on how racial, gender, and sexual formations were challenged, solidified, and reconfigured by material commodities, especially literary texts, over the course of the 20th century. Korey has lectured in the “America in World Civilization” sequence in the University of Chicago’s Core undergraduate curriculum. Other teaching interests include post-Emancipation African-American history, and the histories of gender and sexuality in America and Europe.

Katie Heaney

Katie Heaney is the published author of Never Have I Ever and the upcoming novel Dear Emma. She is an editor at Buzzfeed and has written for New York Magazine and Pacific Standard, among other places. She is a graduate of Illinois Wesleyan University and the University of Minnesota.

Karen Karbo

Karen Karbo is the author of fourteen award-winning novels, memoirs and works of non-fiction including the best-selling “Kick Ass Women” series. Her 2004 memoir, The Stuff of Life, was a New York Times Notable Book, a Books for a Better Life Award finalist, and winner of the Oregon Book Award for Creative Non-fiction. A recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Fiction, Karen’s three adults novels have also been named New York Times Notable Books. Her short stories, essays, articles and reviews have appeared in Elle, Vogue, O, Esquire, Outside, The New York Times, salon.com and other magazines.

Marianne Kirby

Marianne Kirby is a writer and maker currently living in Orlando, Florida. She is the coauthor of the body politics book “Lessons From the Fatosphere” and can be regularly found at xoJane.com, the latest project by Jane Pratt.

Erika Krouse

Erika Krouse is a novelist and short story writer based in Boulder, Colorado. She has been published in The New Yorker and The Atlantic, and she is the 2014 recipient of the Lighthouse Writers Workshop Beacon Award for teaching excellence. Her latest novel, Contenders, will be available in 2015.

Lindsay Moran

Lindsay Moran is a former clandestine officer for the Central Intelligence Agency. She is a freelance writer whose articles have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and USA Today. In 2005 she published her memoir Blowing My Cover, My Life As A Spy, in which she wrote about her experiences as a case officer from 1998 to 2003. After graduating from Harvard, she won a Fulbright scholarship and then became an English teacher in Bulgaria.

Lisa Schwarzbaum

Lisa Schwarzbaum is an American film critic. She was a long-time film critic for Entertainment Weekly, appeared as a co-host with Roger Ebert on At the Movies, and writes regularly about movies, culture, books, TV, and theater. She has written for The New York Times Magazine, The New York Daily News, Time, The Boston Globe, More, and Vogue.

Tynan

Tynan is the co-founder of SETT, a blogging platform that launched in 2011. He was named the King of The Tech Geeks by Gawker in September 2013 and one of the Top 25 Best Bloggers by Time Magazine in August of 2013. His book, Superhuman by Habit, was published in September 2014. He prides himself in exploring the world and connecting with awesome people.

Jeffrey Stanley

Jeffrey Stanley’s screenplay Little Rock, a bio-pic about artist Copy Berg, the first officer to sue the US military for anti-gay discrimination, is currently in pre-production with Pink Slip Pictures. He is the author of the stage play Tesla’s Letters and the writer-performer of his recurring supernatural solo show Boneyards. Stanley has written articles for the Washington Post, New York Times, and New York Press. He teaches screenwriting and theater courses at New York University Tisch School of the Arts and at Drexel University Westphal College of Media Arts & Design. He lives in Philadelphia.

Deanne Stillman

Deanne Stillman is the acclaimed author of Desert Reckoning (2013 Spur Award winner, based on a Rolling Stone piece). She also wrote Mustang and Twentynine Palms (both LA Times “best books of the year”). Currently, she is writing Blood Brothers for Simon and Schuster and the “Letter from the West” column for the Los Angeles Review of Books. Her work has appeared in Slate, therumpus, and the NY Times.

Darin StraussDarin Strauss is a writer whose work has earned a number of awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and the National Book Critics Circle Award. His most recent book, Half a Life, won the 2011 NBCC Award for memoir/autobiography. His ALA Alex Award-winning, best-selling 2000 first novel Chang and Eng was a runner-up for the Barnes & Noble Discover Award, the Literary Lions Award, a Borders Award winner, and a nominee for the PEN Hemingway award. He currently resides in Brooklyn, New York, and is Clinical Professor of fiction at New York University.

Chris TaylorChris Taylor is a journalist originally hailing from the U.K., where he got his start on a variety of national newspapers in London and Glasgow. He has since served as San Francisco Bureau Chief for TIME magazine, West Coast editor for Fortune Small Business, West Coast editor for Fast Company, and is now deputy editor at Mashable. Chris is a graduate of the Columbia University School of Journalism and Merton College, Oxford.

Stephen ToulouseStephen “Stepto” Toulouse hails from the tech industry where he has over 20 years of experience with Microsoft, Xbox, and HBO. Currently he is the Director of Community Engagement for Black Tusk Studios working on the game Gears of War. He is the published author of the book A Microsoft Life as well as being known for his performances as a technology and Geek culture comedian. He’s published several short stories and a spoken word comedy album. He is a pet lover and you can find his writing at Stepto.com.

Glen Weldon

Glen Weldon is a writer, book critic and movie reviewer. He contributes to NPR’s blog, Monkey See and is a regular panelist on NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour. He is the author of Superman: The Unauthorized Biography, a cultural history of the iconic character. His next book, on the intersection of Batman and nerd culture, will be published in 2015.

Marco Werman

Marco Werman is the host of PRI’s The World. He is an Emmy award winner for his short documentary “Libya: Out of the Shadow” on the PBS program Frontline/World. Werman is also the co-creator of the PBS series “Sound Tracks: Music Without Borders.”

Saul Williams

Saul Williams is an award-winning poet, musician, actor, and performer. He recently starred in the Broadway musical, Holler if Ya Hear Me. and is currently working on an untitled book of poetry on America, commissioned by Gallery Books, and his forthcoming album Martyr Loser King. He is a graduate of Morehouse College and New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts.

Bill Willingham

Writer and illustrator Bill Willingham began his career in the early 1980s and is still producing stories for comic and prose readers today. He’s the writer of several comic books, including the long running Fables series, and the author of the novels Peter & Max, Down the Mysterly River and Lady of the Lake (forthcoming).