The Ghost of My Father has received some of the best reviews of all six of my books. I’m grateful to all 247 of my kickstarter backers for supporting this ambitious project about family, memory and making sense of myself.

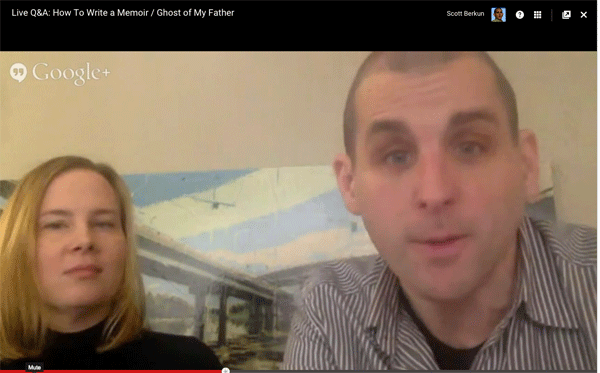

Recently I did a live Q&A about How To Write A Memoir. It was a reward for the book’s backers. This post is a summary of the advice I shared. Thanks to everyone who tuned in and asked questions (and helped me keep the lights on).

1. The two truths of writing anything

There are only two things you need to write any kind of book.

- Good habits. Books take time to write which means your success depends on regular habits. It’s a marathon. I know the way my psychology works I either need to write every day or I won’t write at all. It’s a muscle I have to use regularly to have it perform the way I want it to. How does your psychology work? You need to know. My advice is simple: have a set time every day, before you go to work, after dinner, before you go to bed, that is permanently reserved and protected by hungry Rottweilers, for writing. It needs to be something you do daily without debating each time.

- Commitment. Your writing time will come from somewhere. You’ll need to give up one TV-show a night, spend less time with friends and family, or get up earlier each day. No writer in history has written anything without sacrificing time they could have spent on something else. And when you show up for each writing session turn everything else off that distracts you. You might only put a sentence or two down a day, but if you keep showing up that’s all you need to eventually finish a book. If I don’t feel like writing I’ll show up to my session anyway and commit myself to sitting and thinking about the project, or staring at the blank page. That’s commitment. Usually I’ll get so frustrated in a few minutes with how idiotic I feel having nothing to say that I’ll eventually start writing about that. And then, soon, I discover I do have something to say about the book I’m working on, and before I know it I’m writing. But I have to show up and put the time in. There is no other way.

When people fail with a writing project there are only two causes: bad habits or lack of commitment. If you are committed you will continue to experiment with your habits until you find one that works for you. And if you only manage a paragraph a day, as long as you are patient you will, eventually, have a finished draft. But there is no trick to avoid the work: every writer in history had to put in the hours and you will too.

2. What books or resources do you recommend for writing a memoir?

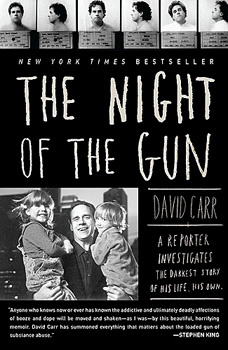

- Read what you want to write. How many memoirs have you read? Go read some. You can’t write well in any genre unless you are well read in it. You’ll discover how many different ways there are to approach point of view, style, tone, pace, chronology and more. Here’s a list of memoirs I recommend.

- Thinking About Memoir, by Abigail Thomas. A simple, short book that explores the basic concepts of what a memoir is and how they work. It includes writing exercises and encouragement. There are many basic books like this one, but I liked it’s concision and straightforward style.

- The Art of Time in Memoir, Sven Birkerts. If you write a first draft and read it, you’ll discover the core challenge of memoir is how you, as the narrator, move through time. It’s the spine that makes a memoir work or not. Of all the books I read about memoir writing, it was this book that helped the most with the central challenge of time. The book referred to many memoirs I’d never read before, which I needed to read (at least partially) to fully understand his points, but that was time (ha ha) well spent. The only way to understand the different ways to handle time was to read another writer and experience the choices they’d made.

- How To Write A Memoir. This short Reader’s Digest post by Joe Kita is surprisingly good and honest.

3. A memoir is not an autobiography.

A memoir is a true story about an aspect of your life. An autobiography is a comprehensive telling of you life story. This gets confusing because we often hear politicians or celebrities talk about writing “their memoirs“, as in plural, which really means autobiography. Autobiographies are much harder to do well, often span 600 pages and are far less interesting to most people.

A memoir has more creative freedom in the themes, narrative styles and storytelling techniques you can use. There are memoirs about childhood, travel, family, competitive sports, starting a company, almost anything. Rebecca Solnit bends the very idea of memoir by combining elements of history, personal stories and journalism together. The unifying factor is the the book is a true story told in the first person about events that primarily happened to the narrator on a singular theme (at least in the writer’s mind).

4. You have a secret reason for writing (a memoir). Figure out what it is.

My friend, and trained therapist, Vanessa Longracre was my expert guest during the Q&A. She pointed out that many people think they know why they want to write a memoir, but possess a secret, and more honest, reason. That honest reason might be:

- This will solve my problems

- My estranged father/mother will do X for the first time

- Everyone will know the TRUTH about my brother and will shun/love/hate him

- I’ll finally get the apology I deserve

Having written a book is unlikely to achieve any of these things. Certainly not by itself. A book can be cathartic and the process of writing it can help you think and feel more carefully helping you to understand yourself better. But the fundamental dynamics of a family relationship have very deep causes that are unlikely to be influenced by the existence of a book alone. Do some research and see if other memoir writers got their secret reason satisfied (See this story about a new memoir about a the troubled McCandless family)

People telling you “you have a great story you should write a book” is an insufficient reason. Unless they are gifting you 500 hours of time to do the work, it’s not help. You have to decide your own reasons, the primary one being that you believe it’s a good use of your time to write a book about yourself. I get emails often asking me “Is my book idea good?” and I tell them the same thing: only you can answer that question. My opinion is irrelevant since you will have to do the work.

It’s okay if you don’t know. And it’s ok if your answer changes as you’re writing. But realize you probably have a fantasy about your motivations. You’ll write a better memoir if you dig deep to sort out what it is you are truly after.

5. Why did you write The Ghost of My Father? What did you want to get out of it?

When this crisis happened in my family I talked to my mother and brother often. These were long, intimate conversations about our family and how we felt about what was happening. It’s a crazy story and we’d laugh at times about how absurd it was. I said to both of them “this should be a book” and they agreed. I don’t know at the time they knew how serious I was, but I’m a writer. This is what I do. A powerful, complicated true story landed on me and I committed myself to telling it.

I wrote it for many reasons. First, I was obsessing about my father and my family and I needed a constructive place to put that energy. Second, I’m a writer who wants to take risks and this was going to be a different kind of book. Third, all families have problems. What we don’t have are the skills and courage to talk about them. I felt if I told my story well it could help readers figure themselves out. This is what good art is supposed to do: help us understand the human condition.

6. There is power in writing without publishing.

I’ve kept a private journal since I was 19 years old. It started as a class assignment, and most of my early entries are embarrassingly shallow attempts to impress the professor. But after the class I kept writing in it. I found that trying to explain whatever I was thinking or feeling in words had a power, even if no one read it. It forced me to think and feel carefully, and when I wrote something down, even if it was expression of confusion or uncertainty, I always felt like a burden had been lifted. Seeing the words on the page made me feel more comfortable with myself. And then I discovered that going back to entries in the past and comparing my feelings in the present was transformative. Written words persist far better than our memories do, and writing your thoughts down is a gift to your future self.

You don’t need to publish writing for it to have meaning. You can also choose to share what you write with only with a friend, or family. You can decided after you’ve written a draft whether you want to publish it or not, or who you’ll publish it for.

7. How do you deal with the situations you don’t remember precisely? (e.g. names of places, people, what happened exactly, what people said, etc. )

Writing is never neutral, completely fair or perfectly accurate. There are long debates among writers about what poetic license is, and how far a (non-fiction) writer can go in shaping or crafting true events: it’s a complex subject I’ve written about here.

Human memory is highly unreliable and anyone writing a memoir must admit this. Keeping a journal helps as at least you have a written record of what you thought on the day certain things happened. Interviewing other people who were there when events happened can be critical as two or more sources dramatically improves the quality of the facts.

Most important is to disclose to readers what sources you had. Few memoirs do this and it’s a mistake. In most memoirs quoted passages (e.g.’and then Todd said “this is the worst Atari game I’ve ever played!”‘) are inventions based on one person’s recollection of a conversation. How accurate can this possibly be? Unless the author had a tape recorder playing 20 years ago how could they possibly remember the exact quote someone said? They can’t. But written storytelling works better when this kind of precision is provided, so many writers claim poetic license to fill in these gaps.

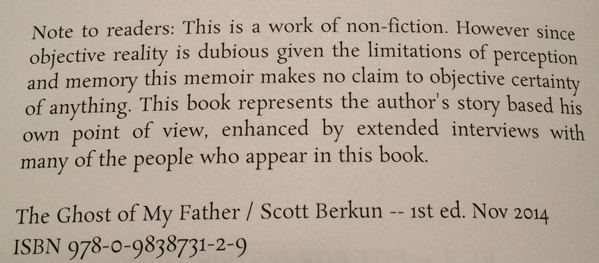

I think whatever you do is ok provided you explain to the reader somewhere what you did or didn’t do. Here’s what I included on the first page of The Ghost of My Father:

8. Were there periods of doubt while writing this book that were more severe or different than what you have experienced before? Were your habits always strong enough to alleviate these doubts? If not, what parts of your life helped you rebound?

Yes. All ambitious projects come with periods of doubt. If I work on something and never have doubts it means I wasn’t ambitious enough. This is my most personal book and everyone in my family who is in the book is still alive. But I’m a writer. This is what I do.

The habit that matters the most is having faith in the next draft. In each draft I had a chance to reconsider what stories I told and how I told them. I had 5 people read early drafts of the book, people who I know are honest with me about their feedback.

9. Did you have any fears or concerns about how being this vulnerable, personal and open would impact your perception and opportunities with your harder core business audience?

I’ve had some practice with sharing private thoughts publicly. I wrote a popular book in 2009 called Confessions of a Public Speaker, so I’ve confessed on some things already. My previous book, The Year Without Pants, is a first person story of my experiences leading a team. Of course The Ghost of My Father was far more personal, but the experience with being honest with readers is something I’ve been developing over time.

I want to take risks with talents. To do that means doing things I’m afraid of. I want to bet on fans. If I publish a book they’re not interested in I hope they’ll just wait for the next one.

10. What does a personal memoir need in order to be popular (have high sales) if it’s not about someone who is already in the public eye? Does it need a character arc? Or a realization of a profound truth? What makes it interesting to the reader?

Selling books is harder than writing them. There is no formula. In broad strokes memoirs are harder to sell than novels or non-fiction books. Being famous helps of course as people are interested primarily in the person, not the book. A big part of any book selling well has little to do with the writing of the book. You have to identify the audience, find ways early on to reach out to them, write a great book, and then work hard to let them know you’ve provided something they want. But the more you write a book to sell it, the less soul the book will have. Making true art demands goals with more depth than sales numbers.

11. Being such a creative mind and tackling so many topics in your blog, how do you decide on a topic & outline for a book? How do you handle “book being already written”, “same old topic”, etc? Really, how do you write great books on topics already addressed?

Every topic has already been addressed many times. So what? If you read the Greek tragedies you’ll discover Shakespeare stole their plot lines. And then if you watch the Lion King you see it’s Hamlet for kids. No one really cares how original it is in the abstract, they care about how good it is in the specific. See It’s Ok To Be Obvious for my take on this philosophy. If you have an opinion go read what someone else said about it. I bet you’ll find you disagree with them or have a better way to express a similar idea. Don’t hide from it, build on it.

11. Did you consider writing it as fiction even if it’s mostly true to avoid the issue of criticism of your decisions?

Telling my story as fiction felt like cheating. Many writers have done this and I’ve often wondered why. Even Charles Bukowski wrote Ham on Rye as a novel, despite it being the story of his childhood. In this case I asked myself: am I telling a true story or not? If I am, why call it a novel and introduce doubts? If I’m a good storyteller why do I need to invent things to make it work? Anyone in my family who read the book as a novel would easily identify who they were. So why the ruse?

My complaint about so many films and TV shows about family is how phony they are. And since these are the primary ways we learn about families other than our own they perpetuate the same fantasy mythology about what real families are like. Where does most of your knowledge about relationships come from? Much of it is from fiction and I think that’s part of the problem. Of course fiction can illustrate some things better than non-fiction, but in some cases the opposite is true.

I know many authors wait until their parents are dead to write about them. This feels like cheating too. Superficially it seems like respect to wait until after someone is dead to write about them. But think about that: it takes away their rights to respond. It’s actually a betrayal. It’s a permanent way to go behind their back. There is nothing in this book I haven’t said, or wouldn’t say, to everyone in my family. Does that make me brave or stupid? Probably some of both. To put it another way: how I can consider someone close to me if there are deep things central to who I am that I can’t share with them? Or share, as an illustrative example, as a writer, with strangers? We talk about transparency and honesty but do we practice it in families? in tribes? Cultures?

You can decide if you want to fictionalize your story later (and here’s advice on how to decide). Don’t get hung up on this. You’ll write many drafts and it’s a decision you can start worrying about once the first draft is done.

12. Did you come to have a different understanding of forgiveness? As a human ability or valuable choice?

I want to say yes, but it’s hard to be sure. The cliche of forgive but not forget is true to me. I don’t hate my father. He is a lost person and I feel sad for him, as he’s his own worst enemy. And I do understand, now, that his failings as a parent have more to do with him than with me. But forgiveness is not a panacea. Dysfunctional families are not fixed through forgiveness alone. Here’s a more important question: if you are in a relationship that is inherently destructive for you, what obligations do you have to stay in it? And how deeply? That’s not about forgiveness so much as it is about figuring out how to be a healthy person. How do you create healthy boundaries on territory you know is dangerous to you? That’s the hard question. There’s no platitude for solving that one. It’s the struggle most people have in their families: how can I be myself in here? I love these people and they love me, but then why does it hurt so much to get close? It takes hard work to learn healthy expressions of love.

———————————————————————-

You can buy The Ghost of My Father on Amazon. Kirkus Reviews called it “A sobering, lucid memoir about the uncanny, precarious nature of family, masculinity and childhood.” Profits from the first edition of the book are donated to Big Brothers Big Sisters.

If you have other questions about writing, or writing a memoir, leave a comment.

My friend and fellow author

My friend and fellow author