I spoke this morning at Prototypes, Process and Play, in Chicago about The Dance of The possible (slides, sketchnotes). Here are my notes from the sessions so far.

Leadership is the reduction of uncertainty in an organization – Paul Pangaro

Reference: The Little Grey Book on Leadership, Paul Pangero

Question: how do you help reduce uncertainty? Perspective, principles and practices. Creating confidence by reducing uncertainty. The challenge is that then average Fortune 500 company lasts 15 years. A company needs to find a way to replace an entire better business while it’s still running.

He used to think CEOs were stupid. They say the same simple stuff over and over again. Now he realizes repetition is everything. “By end of the decade, we are going to put a man on the moon” – Executives have to deal with huge amounts of risk, and repetition and clarity is one way to provide it.

- Designers (Engineers) ask: What is possible? How might we do it?

- C-level asks: Can we do this, should we do this?

Tesla’s Secret Plan – Great example of a CEO managing risk right.

- Build a sports car

- Use that to build an affordale car

- Use that to build an even more affordable car

- While doing above, provide zerio emission power

- Don’t tell anyone

General Principles:

- Don’t start from scratch

- Set high level goals, not detailed path

- Break into small steps

- Address big risks as early as possible

- Prototype your way into production

The risk of deferring risk

- You don’t know what you don’t know

- You push the unknown into the future

- Your exposure to unknown compounds

Test your biggest risks first – often it’s not design risk, it’s technological risk.

RAT: Riskiest assumption test – It’s more important to vet risks first than to explore what’s possibly viable.

Innovation is s search problem – The pivot approach works fine when you are small and fast, in a small startup. But for large organizations you need a portfolio.

3. Carmen Medina, Lead Above Mediocre Thinking

She worked for the CIA for many years, and for a time, in/on South Africa. They had a ‘design problem’ called apartheid. Led her to ask the questions: What is good thinking? What can we do to do better thinking? She had a great group of analysts, but were so divided on fundamental questions: how soon will black majority rule come to SA and how disastrous will it be?

Thinking Errors

- Street Lights – we base our decisions on information is readily available. CIA had bias like Regan administration views, the questions we asked our sources, etc. (No one asked Sadam’s people in IRAQ if he had gotten rid of WMDs).

- Trends. We assume trends are about the future, but trends are about the past. The years leading up to the stock crash of 1929 look normal and positive.

- “X happened by chance” – what does that mean? Nothing happens by chance. What we’re really describing an event whose causality we do not yet understand.

- Exponential causality – When one event happens it doesn’t have one effect, it has a multiplicity of effects.

- Worst Case – we tend to conflate worst case scenario with low probability.

“There are no solutions only tradeoffs” – Thomas Sewell

Solutions are rare, tradeoffs are common – so your value system plays a big role.

Ways to lead better thinking

1. Develop an Analytic Landscape – she gave these instructions to her research teams:

- work independently

- engage outsiders

- provide a graphical presentation

- Don’t simply document what you already know

2. Articulate Thinking Strategy – Complex situations are dangerous because experts try to reduce a problem into boxes they know, when you want/need to admit the problem isn’t simplifaible.

3. Know your thinking Style – What appeals to you and what do you tend to like? Find a thinking partner who complements your style. This broadens the analytic landscape and reduces bias.

4. Think Together from the start

5. Respect your intuition – when your mind tells you something without thinking it in words. Our thinking capacity can be different, or larger, than our word capacity.

Her book: Rebels at Work : A Handbook for Leading Change from Within

A manager/leader must make clear their ideas are not above debate. These questions help:

- What did I get wrong?

- How would you do it differently?

4. Julia Keren Detar, user research on shoestring budget

Hyatt (where she works as director of UX) is in the business of hospitality. There was a time in her life when she was in despair, so she took the day off and read about the neuroscience of happiness.

Brains are more fertile for weeds than flowers ( “can I eat it or mate with it?”, vs. “can it hurt me or kill me?”). Negative bias keeps us alive: great for survival, but bad in some ways for modern life.

The Amygdala in our brains triggers the fight or flight response, even to negative events. The Hippocampus stores the memory of even a minor thing, in an attempt to prevent it happening again. It’s easy for small loops of negative experience to dominate how we feel about the world.

Neuroplasticity – the more (or less) you use a pattern, the more or (less) well or easily it fires.

7 suggestions:

- Mindfullness – Headspace, buddhify. Easy exercise: close eyes, take a deep breath, let it out and think about the comfort the chair you are in is providing.

- Reminice – thinking about good memeories is a way to bring positive mental states back into the prescent.

- Walk it off – Any exercise that increases your heart rate for 20 minutes or more releases endorphines.

- Feed your brain – Borccoli, Spinach, Avocados, Walnots, Almonds, Blueberries

- Genorisity – happiness is making someone happy

- Give thanks – acknowling how people have been good to you

- Play time – if needed, schedule time for play (she schedules time to play with her team, an afternoon every month – board games/etc.)

Having a seat at the table doesn’t mean anyone will listen to you. You need to have a story that explains your purpose, goal and narrative that is compelling to people you encounter.

What scientists tell us is story, or narratives, developed through evolution as a very powerful way to communicate and get people to listen to us.

Walt Disney told the story of Disneyland “a place where the parents and the children could have fun together”. This kind of clarity is what she wanted from her CEO, but didn’t get.

Alex Bloomberg, who is a master of storytelling (podcasts) utterly failed to tell the story of his own business idea – storytelling can be hard, even for people who are skilled at storytelling, if they’re deep in the details. Good storytelling means stepping back to see a bigger picture and telling that, often much simpler but stronger, story.

She led her team (fitness app) in story discovery exercises, the first of which didn’t work well. It was hard. She arrived at thinking of her team as story sleuths – a different way to think about product design. Instead of the traditional skills, it’s about being willing and motivated to sort through all of the possible stories for a project and decide on a primary one. She used the apple iPhone design/experience, from opening the box (e.g. OOBE – out of box experience) to how Jobs demoed the iPhone focused on telling a story (Google maps was the premier app, and he showed the way the pin ‘bounces’ as it appears as the conclusion of the story at the heart of the demo).

Disneyworld had problems with customer traffic in the park. They created a team (FAB5) to solve the problem, and they eventually came up with the Disney Magic Band. One device that let you access everything: hotel room, the park, rides and more. They employed some of the same story techniques that Disney teams used in their films. Including prototyping and simulating design ideas and learning from those experiments.

“you get to the be hero, promising a ride or a meet and greet. Then you’re freerer to explore the park” – Disney, COO

She applied some of these same ideas to her product team, and as they built their story they realized they needed to redesign and reconfigure many of the core ideas, from design to business model. This violated her rule of “don’t do redesigns” – but she realized that many of their past struggles was because the story wasn’t clear. They made redesign prototypes based on the story to help convince management. For her startup, the stakes were relatively high for the company, but not the same as what would be for a billion dollar product.

For FAB5 the stakes for Disney were billions of dollars. They brought executives in to experience a walkthrough of the simulations of their ideas, based on the story.

When you have a story floating through a system (organization) it helps all points of connection and relationship to work more smoothly.

Questions to ask:

- what is the story?

- who is your hero?

- what is their goal?

- how do you make this story happen?

Book – the user’s journey

7. Lisa Welchman, Governing With Intention

Seduced from her voice major to study philosophy (suggesting the power of a good teacher), which led her on a path to work on the web in the early days. During this time was clear to her that even Cisco (where I think she worked) couldn’t manage their website, despite being in the middle of the early internet. IT and marketing fought with each other. This kind of work is hard, especially at scale, and has natural tensions that are hard to remedy.

Governing things is just being clear about who is accountable and who makes decisions. While everyone has good intentions, a lack of clarity creates problems.

Q: How can I work with people, create something of value and still maintain a sense of personal agency and autonomy?

“It’s just work” – it’s not just work, work is a big part of your life.

“Organizations are a competition between compliance and creation” – Kevin Ashton, How to Fly a Horse

It’s a fallacy to think that work in an organization can be “done:. “When is digital going to be done?” is an absurd question. It’s a living thing. There are always new things coming in and others leaving, nicely or violently.

It’s important to clarify before meetings and processes begin:

- Who should inform strategy?

- Who should frame policy?

- Who should define standards?

- Who should be in the room?

Standards do not restrict creativity – by constraining certain decisions other things are liberated:

- Speech, Music, Movable type, Our genes, Telephony, computing (languages), the WWW, etc.

- Policies (which are a kind of standard) protect the organization and provide opportunities

Murmuration – how birds move in flocks. They pay attention to the nearest 7 birds around them, They don’t need to know what all the birds are doing, but some simple rules useful patterns emerge.

(this was a live interview on stage with Russ Unger – these are my rough notes on what was a fun and insightful conversation, but hard to capture)

Mike was VP of Design at Twitter, which had a staff of 100 people when he left. He’s been on sabbatical for over a year.

Twitter can be a poor place to discuss something that involves nuance. It becomes more of a performance where each person is performing for their followers, where you say things you’d never say face to face. Not a great place for design critique in particular, where the goal should be helping the designer do better work.

It’s common in the industry to see designers prefer to work in isolation, as it’s a natural way people learn, and are drawn to the field. But it’s not that useful in a workplace with different specializations and teams.He doesn’t like the term soft skills – it’s really just being a good person and teammate and valuing relationships.

Revisionist history: after a project launches and doesn’t do well there’s often a recasting in organizations of the initial premise and risk threshold – “who approved a project with a 25% likelihood of succeeding?” even though that was deliberate and done with strategic intent to take risks.Bezos – I want Amazon to be the best company in the world to fail at.

Design teams need to have two sets of goals: for the design team and for the rest of the project team. A goal like “every pixel counts” makes sense for designers, but not necessarily for an engineer. You need goals that are shared and sensible across the organization too.

As a manager he wanted to be sharp enough with individual designer skills for two reasons: to be able to empathize and understand what his staff is doing, and also to be able to call bullshit and challenge assumptions.

Many designs launched without his direct approval. They had a weekly product review, with the CEO and other important people, where every team would show their prototype and discuss it for an hour. One week, the events team came in and the designer showed something he’d never seen before. And his heart went into his throat. The CEO turned to him and asked “what do you think?” And he made it through the meeting ok, but turned to the designer after and asked them not to do this again.

People think companies are like a single threaded organization, like a kids soccer team, where everyone just follows the ball. But this is rarely the case.

Conway’s law– “Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”

Basic rundown on his design leadership / management roles:

- Design manager level 1 – focus on team, little studio/company influence

- Design manager level 2 – more influence across the design studio

- Director level – must pick something that improves the entire design organization

- Senior director – must influence the entire organization in some way

Decision quality is different from Outcome quality. A good decision can lead to a bad outcome, and vice-versa.

It’s fortunate to work on a project important enough for people to complain about it visibly in public. Most designers don’t get the opportunity to work on things that visible or important.

Day 2

She was a Time correspondent during the government shutdown years ago. Around the same time The senate reached 20% women for the first time (113th Congress).

Critical mass – point at which a chain reaction can not be stopped. When they integrated schools in the U.S. they decided critical mass was about 20%.

Public sector is often better for women:

- Lower wages means less competition for jobs (which, sadly, works to women’s advantage)

- Unions are stronger (and able to get maternity leave / etc.)

- Bosses are different – you answer to voters and women vote more than men do (on avg 10%, and make up 53% of voting electorate)

Facts (unsourced):

- CIA is 47% women.

- 17% of mayors are women

- 5% of governors and

- 5% of fortune 1000 CEOs.

- Some stats are hard to find: what % of police officers are women? No one knows. It’s all local data (rough estimate nationally is 14%). There are some initiatives to get better data.

The glass cliff: women put in power are pushed off the cliff if they don’t succeed.

Women are often judged (unfairly) for trying to inspire or speaking with power. Hillary was criticized for being shrill, yet Bernie Sanders could have been criticized similarly at many of his speeches, but rarely was.

We had universal child care during WWII, while women dominated the workforce. But it wasn’t until the 1970s that all of the laws preventing women from working without their husband’s permission were finally repealed.

By the year 2030 this generation will age out and the U.S. workforce will be short 2 million workers. There’s two ways to solve it. Immigration, which is hard to imagine. Or you open it up to women in the workforce. Women already have the talents to do this. They make up half of college degrees. They’re just not using them. But this is not going to happen naturally. It’s something that’s going to have to be invented. Child care. How you get women sort of free enough to take on the bigger jobs. And part of that comes from men helping. The next generation is millennials. They are the first generation born assuming equality in the sexes. They’re the first generation born to working women. It’s a hallmark of their generation. They actually have a lot more equality than other generations.

Asked about it by the audience, she felt the premise of the recent Google memo was ridiculous, citing evidence from the beginnings of the software industry and how it was dominated by women. But that was lost in the last couple of decades largely because of society’s changing view of what is sexy or appropriate for women to do.

She was asked what to do in the workplace to work against gender bias. She suggested:

- Make allies (with other women) – often women have equal numbers, but don’t act to support each other in meetings in the ways men sometimes do

- Obama suggested to his female staff (who complained about bias) that they need to have dinner together regularly to form bonds and connections that will manifest in the workplace

- Stand up for other women – if you observe a woman suggest something that’s ignored only to have a man successfully suggest the same thing later, call it out and help her get credit

- Don’t fall into the trap of doing menial work your peers don’t do – it’s easy (in some workplace cultures) to be seen as being in a lesser or supportive role, especially if you are new to the organization

Her book: Broad Influence: How women are changing the way America works.

The term broad originated years ago as a reference to women’s broad hips.

Australian advocacy group: Male Champions for Change

10. Dr. Steve Julius, Getting a Seat at the table

“It isn’t that they can’t see the solution. It’s that they can’t see the problem” – G.K. Chesterton

“I have so much to offer, but I feel they don’t want to hear it” – the truth might be you have to wait for an opportunity, perhaps over weeks or months, for the timing to be right.

Four levels of breadth/depth (of work relationships):

- Service Offering

- Needs Based

- Relation ship based

- Trust based

5 principles

- Know your stuff

- Uncover Ways to Add Value

- Be Credible

- Execute

- Listen

Think like an anthropologist

- Observe and learn before you act

- What is the power structure? What language do they use?

- Where do the real decisions happen? (at happy hour? At golf?)

- Adapt your approach, speak their language

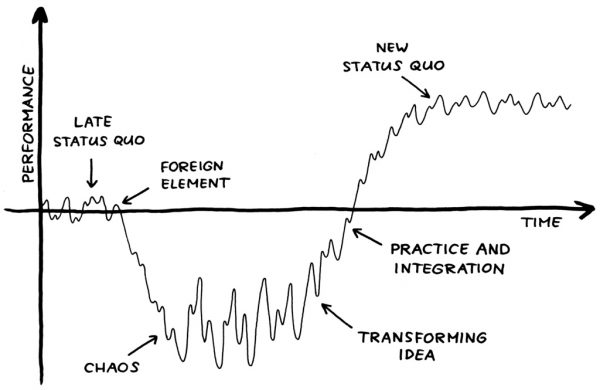

Stages of Change

Formal vs. Earned authority

- What is my purposes?

- How does my narrative convey the idea?

- How best can people put my idea into practice?

- Who do I really want to reach?

- Do I have meaning supporting material?

“It is easier to resist at the beginning than at the end” – Leonard Da Vinci

11, Dan Brown, Achieving The Right Mindset

Card game – Surviving Design Projects

Where do you start when a client shows up and tells you what they want?

- Who is your audience?

- What are your underlying assumptions?

The questions you ask, and work with clients to answer, start big and get smaller as you go through the design process. He calls this the discovery process and the goal is to created a shared pool of experience (‘remember when we did that user study?’) about what worked and what didn’t. It’s best to think of discovery as a mindset.

Mindset means how we:

- Perceive

- Understand

- Choose how to react

It’s often hard to work with other people – people are weird! But mindset helps. What do we perceive? Maybe we or they misunderstood something that needs to be clarified about their behavior than once understood changes how we react.

Critique sessions that go wrong can be thought of as failure of mindset. Some people see critique as a fight, or a way to get revenge. But a healthy critique mindset is that your coworkers are there to help you improve your ideas, and you theirs.

Carol Dweck’s Mindset: The psychology of success –

Fixed Mindset vs. Growth Mindset: things you refuse to do because it may undermine your sense of your self vs. things you willingly choose to embrace.

Six more precise mindsets:

- Adaptability: ready and willing to try new things

- Collective: use other points of view and inputs

- Assertiveness: working with incomplete knowledge (‘here’s what I do know, and what I can try to do to resolve what I don’t know’)

- Curious: excited to learn new things (ask questions, talk to new people, follow hunches

- Skepticism: don’t accept assertion at face value

- Humility: You need to be bold (in growth mindset) but be humble about the prospect of learning or having your assumptions challenged by new information. Listening is an act of humility. As is asking someone to teach you or give you feedback. Saying “I don’t know” is healthy and invites people to contribute. It’s good to ask “How am I learning on this project?”

“I don’t get further by hoarding credit” – a bonus behavior is crediting other people.

“Ask questions like everyone else is wrong. Explore them like you are” – Emily S. Klein

Mindsets translate perceptions to actions. List of actions:

- Ask questions

- List assumptions

- Say I don’t know

- Follow Hunches

- Play devil’s advocate

- Find improvement everywhere

12. Kathi Kaiser, How to start a company

Design methods (Set goal, gather data, prototype, test, iterate) apply to anything, including designing a company.

Starting a company starts with the hierarchy of needs: basics first.

- Physiological: Food on the table

- Safety: Steady Pipeline

- Social: Nice Clients

- Esteem: Cool Projects

- Self Actualization: Work hard, play hard

In the early days, with a small organization, this was straightforward. But as the company grew, this wasn’t enough.

- Self transcendence: the act of helping others self-actualize

People first: you take care of your staff, your staff takes care of the company

Their first office design was a disaster: the owners were up in the loft, literally looking down on the staff below. They redesigned, involving the team, prototyped alternatives, and found a much more workable arrangement.

An experiment they tried was to involve the staff in leading projects that were ‘backoffice’ like setting up health insurance, or suppliers for equipment, and to their surprise most of the staff was motivated to own these kinds of projects.

13. Suzanna Bierwirth, Managing Up, Down and Sideways

[Also see Amy’s notes – they’re better]

The wrong reason to be a manager is to get a salary raise. You may promote a designer to a manager, and lose a good designer and get a bad manager.

To be a manager means you are no longer judged for your individual work, but by what the people on your team produce. Delegate or die.

- Know your people’s strengths and weaknesses

- You are responsible no matter what happens (if they miss a deadline, you didn’t give them enough resources)

- Know how key people like information delivered to them

- Never let your boss be surprised by bad news or something going wrong

- Pitch needs in a way that ties to your boss’s goals – don’t say “I need more staff”, instead say “I’m turning down jobs – there’s too much work to manage.” They will likely suggest the natural answer to the problem, and you are more likely to get what you want

13. Eli Silva, Designing for Diversity

Hurricane Sandy took out large portions of NY and NJ in 2012. The scale of the disaster made responses challenging. People didn’t know what the Red Cross was doing (Propublica wrote a story about it). Eli was there, working on Occupy Sandy, a grass roots response – it has shaped the way he thinks about design.

It was his first organization design exposure – an org designed to meet real human needs.

Advanced persistent neglect

Often PD and OD have different value systems:

- Product Design: listen to user. Test. discard. Ask question. Clarify. Repeat.

- Org design: welcome to your desk. This is who you report to. Please keep you hands feet and questions inside the dominant paradigm and role based structure at all times.

A better culture demands we challenge assumptions where they are most entrenched. And apply some principles from products to organizations.

“Some people don’t like to take responsibility for their own shit. They blame everything in their life on somebody else.” – Uber CEO, Travis Kalanick

Diversity debt – impacts of not having a diverse set of people, ideas and cultures in your organization. Often created from short term tradeoffs or ignorance.

Mckinsey Report of 366 pubic companies showed bottom line benefits of diversity.

Google spent $265 million on the effort to improve diversity and it mostly failed.

Even the most powerful ideas in the world cannot survive persistent institutional dysfunction.

- Inclusion – creating conditions for org reflection, course correction and change by design. Saying “I have an open door policy” is not sufficient to ensure that policy is used effectively.

- Participatory design – approaches that invite all stakeholders (employees, users, citizens) into the design process to better understand and meet the complex needs of everyone

Things to do:

- Are your job postings biased?

- How many under represented people even make it into your hiring pipeline?

- What is their attrition rate in first 90 days?

- Is their an inclusion officer? Visible inside the org? To the public?

- Embrace the idea of ‘culture add’ – make it a priority to invite people into design conversations likely to spark meaningful debate

- Is their training for unconscious bias?

- Do your exit interviews and 1-on-1s include any discussion of these topics?

UX/Business/Tech -> People/Advocacy/Practices -> Balanced People Team