5 Questions that decide if Facebook crossed the line

There are 4 points and 5 questions at the heart of the latest drama around Facebook and ethics, and the report of a recent experiment they did regarding emotions.

1. All media manipulates emotions by design

Newspapers editors have always chosen which news stories we see, choices made with emotional impact in mind. Television and print news have a long history of over-reporting stories of violent crime, far out of proportion to the rate they happen. One argument is the belief it’s easier to draw attention for negative stories. Another is that making people feel bad eases the challenge of selling them things in ads (See Do Emotions In Ads Drive Sales?). The news feed from any news source has always been editorialized, or in more cynical terms, manipulated. There has never been a news report that is purely objective, although some are more balanced than others.

Advertising by definition is “a form of marketing communication used to encourage, persuade, or manipulate an audience” (#). Television, print and web news generally depend on advertising for income. Any service you use that depends on advertising feels pressure on on all of their choices to help advertisers succeed in their goals.

2. Clickbait and headline crafting are emotion manipulations

News services choose which stories to cover and how to title them. There is a natural incentive to want stories to draw attention, and the writing of titles for articles is an important skill, a skill based on understanding reader’s emotions. Buzzfeed and Upworthy are notorious for their careful crafting of the title of the articles (The Atlantic reported on Upworthy’s successful headline style). The common use of puns (humor), tension (fear), and teases (curiosity) are all based on attempts to use the reader’s emotions to make them more or less likely to want to read the story. Headlines predate the web, and the history of newspapers documents yellow journalism, a practice still in use today.

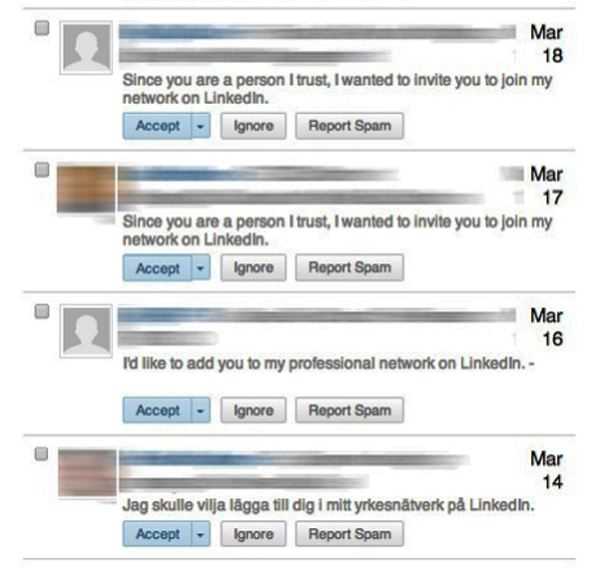

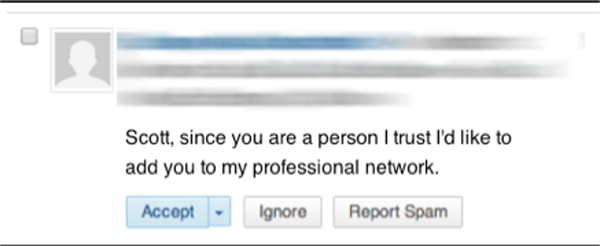

3. Designers of most major websites experiment on their users

For more than a decade it has been standard practice for people who design websites to use A/B testing on unknowing users of a site. These experiments are done regularly and without any explicit user consent. A designer’s job is to learn about user behavior, and apply their knowledge of humor behavior to help their employer with their goals through redesigning things. Any website that depends on advertising for revenue is designed with the goal of selling ads. This includes most of the major news services that have been critical of Facebook’s behavior, including The Economist, The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian and The New York Times. All of them have likely done research on unsuspecting users regarding how design changes impact user behavior.

Most major software companies employ user researchers and user experience designers, people who study human behavior for the corporation. Many of these people are hired for their expertise in experimental psychology. Most formal experiments are done in labs with explicit participant permission, but as software world has shifted to the web, the formality of online user experiments has changed.

4. The Facebook news feed has always been controlled by an algorithm

At any moment there are 1500 possible stories Facebook can show the average user. Much like Google or any search engine, Facebook has an algorithm for deciding which of many competing links (or stories) to share with any user at any time. That algorithm is not public, just as the algorithm in the minds of any news editor anywhere isn’t public either. That algorithm is perhaps the greatest piece of intellectual property Facebook has, and it is something they are likely developing, changing, and experimenting with all the time in the hopes of “improving” it. It’s no accident Facebook calls it the news feed.

Just like any media source, improvements from Facebook’s perspective and a particular user’s perspective may be very different. However all sources of media have some kind of algorithm. When you come home from work and tell your spouse about your day, you’re using a kind of algorithm to filter what to mention and what to ignore and have your own biases for why you share some news and not others.

Facebook is a social network that by its central design mediates how “friends” interact.

5. The 5 questions that decide if Facebook crossed the line

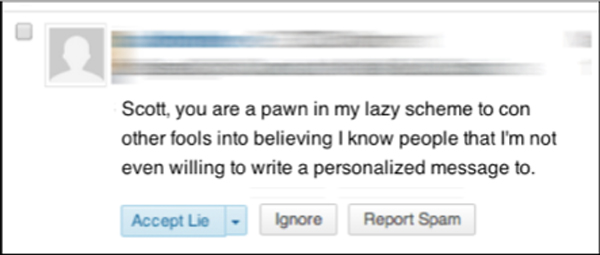

Outrage is emotional itself. When we get upset, based on a headline, we already have confirmation bias about the story. None of us heard about what Facebook did from a purely objective source. We all entered the story the same way we enter all stories, with preconceptions of our own and influences born from the editor and writer.

Ethics gets grey fast once you get past initial emotions and dig in to how one practice compares to others. There is never just one bright yellow line, instead it’s a series of many gray lines, where the details make a difference. There are 5 questions that probe at the entire issue and yield perspective on what’s right, what’s wrong and what’s somewhere in the middle.

- Is it ethical to manipulate people’s behavior? Perhaps, but with media it’s a matter of degree. All communication has the implicit goal of effecting people in some way. All media organizations, which includes Facebook, have a combination of motivations, some shared by their users and some not, for the changes they make to their products. Advertising has strong motivations to explicitly manipulate people’s emotions and any organization that use ads are influenced by these motivations.

- Is it ethical to use design and experimental psychology to serve corporate goals? Probably. This doesn’t mean all experiments are ethical, but using experiments of some kind has long been the standard for software and technology design, and similar methods have long been employed by advertising agencies. There may be nuances that should be adjusted, but in principle research on human responses to media is standard practice and has been for a long time. In the pursuit of making “better” products, research is an essential practice. I don’t think Facebook’s Terms of Service needs to state anything specific about experimentation if the terms of service for news and media outlets that do similar experiments don’t have to either.

- Was there something wrong with explicit, rather than implicit, emotion research? The outrage may stem from this difference. Rather than they study being about increasing clicks, which has implied emotional factors, the stated goal was purely about influencing how people feel. This makes it feel categorically different, even if the methods and motivations are largely the same as much of the research done in most software and media companies. Plenty of magazines and websites have the primary goal of changing how you feel about a topic or issue (e.g. Adbusters). The results from the study were moderate at best – a tiny amount, about .1%, of influence was found. There are other possible issues with the study design, described here.

- Was there something wrong in doing an experiment at this scale? Maybe. If the study had sampled 20 people I doubt there would have been much outrage. Something about the scale of the study upsets people. The rub is that when your service has 1 billion users, a small experiment involves thousands of people (the study involved 689k users, less than 1%).

- Was it unethical to publish the results in a research journal? Possibly. On one hand research journals have specific protocols for participants in studies. But on the other hand, if it’s common for an an organization to do the experiment in private, why is it unethical to report on it? (I’m not saying it’s necessarily ethical, I’m just raising the question)

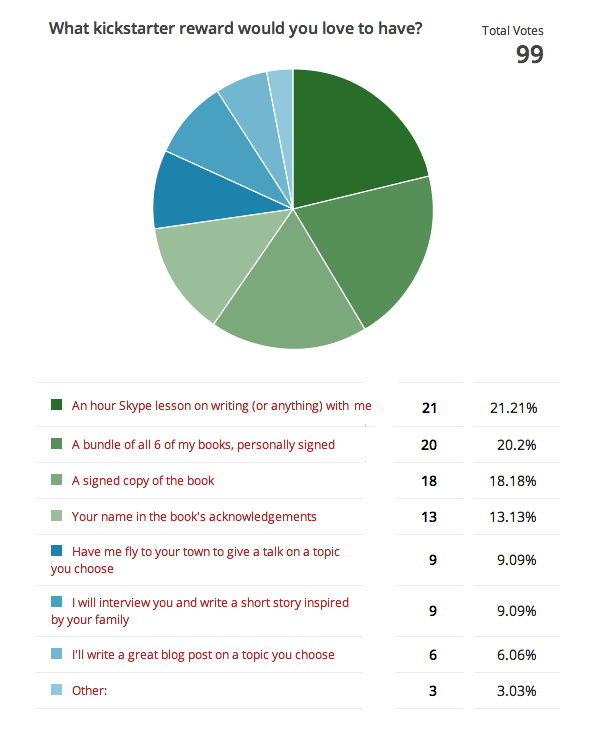

I’m considering using Kickstarter for my upcoming book,

I’m considering using Kickstarter for my upcoming book,