How I Decide What To Read

This month I’m posting every day, taking the top voted question from readers and answering it. With 37 votes, today’s winner was:

How do you decide what to read?

From what I can tell, you are a voracious reader. Do you read just one book at a time, or multiple books at a time? Advantages or disadvantages to either?

I read 20 to 30 books a year, sometimes more if I’m working on a new book and there’s research I need to do. I don’t worry much about what I read. I keep a big supply of good books around and what I read on a given day is driven more by whim that anything. If I buy good books, which one I’m currently reading doesn’t matter.

I read primarily on my iPad through Kindle. It’s convenient given that I travel often, it’s easy to buy new books on the fly, and I like their highlighting system. But I’m not particular: I read print books often too.

I try hard to read one book at a time. It’s very tempting not to, but like all multitasking you waste energy when you switch as it takes time to recall everything that was in the book up until the point you reached last time. If I switch away from a book it’s a good sign I should abandon it completely. If I’m not convinced by the 50 page mark I will abandon a book with no regrets. I used to have 3 or 4 partially read books around but I’ve gotten much better at avoiding that trap.

As long as I’m reading frequently I don’t worry much about what the particular books are. But if you forced me to make it into a formula it’d be something like this:

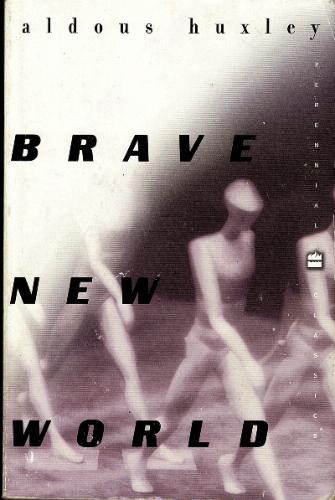

- Books I should read. I’m interested in writing books that will be read long into the future and I read old books that are still read today to learn something about how it’s done. I read many books that were published decades ago and largely avoid trendy topics or bestsellers. There’s plenty of classic literature I’ve never read and I try to knock off one or two of those a year. Some books are purely recommendations from friends who know the kinds of books I love.

- Books related to a book I’m thinking of writing. I have a table in my office with 5 piles of books, each pile represents a future book project. I don’t know exactly when I’ll get to these projects, but I do look for books that line up with future ideas I have for my own projects. Sometimes I put them aside, other times I bump them to the head of the queue.

- Books in different subjects. My strength as a thinker is I have wide interests and I grow that strength by reading books in many different subjects. The last few books I’ve finished include Glittering Images by Paglia, The Origin of Satan by Pagels, A Drive Into The Gap by Guilfoile, and Broken Music by Sting. I rarely read books about management or creativity anymore as I have far less to learn in those subjects than I do about art, religion, sociology and dozens of other ways of looking at the world. I also believe I become a better expert at what I already know by reading different subjects as there are always ideas from one field that can be applied to others and that’s where many breakthroughs come from.

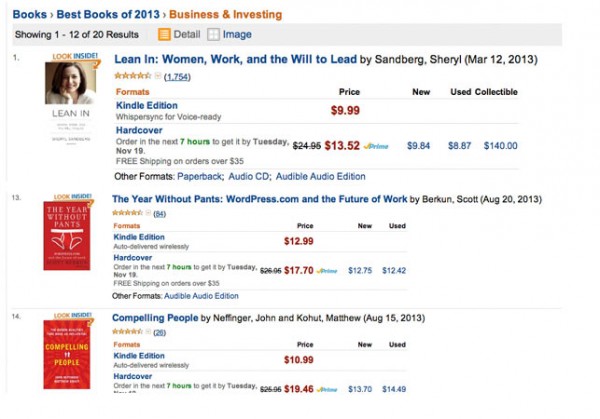

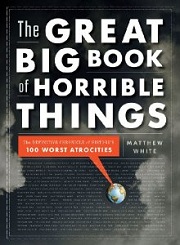

- I rarely read bestsellers and seek more challenging books. The bestseller list is conservative in the kinds of authors and topics that will be widely popular immediately on the book’s release. Plus it’s not a level playing field, which is a surprise to most people. I prefer more ambitious books that are too challenging to ever see this kind of popularity. Zeldin’s An Intimate History of Humanity or The Great Big Book of Horrible Things are good examples. I love books where a smart expert who writes well takes on a big subject without ever claiming a gimmicky solution to all the world’s problems (a sad cliche of the non-fiction bestseller lists).

- I read good writers. I sometimes read books purely because of the talents of who wrote them or the approach they took. Writing is a craft and I want to learn from other craftspeople. I’m a regular reader of The Best American Essay series since it’s an easy way to find new writers and essays are short enough that if I don’t like one I can just skip to the next one.

You can see My Favorite Books and Why I love Them for more on what I read and why.

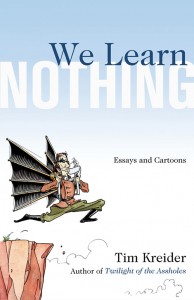

We Learn Nothing

We Learn Nothing

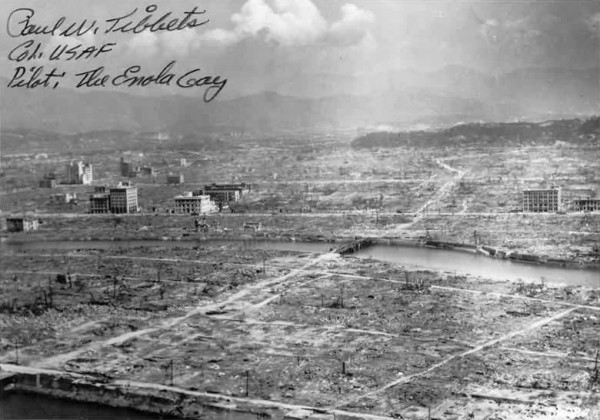

Today is the

Today is the