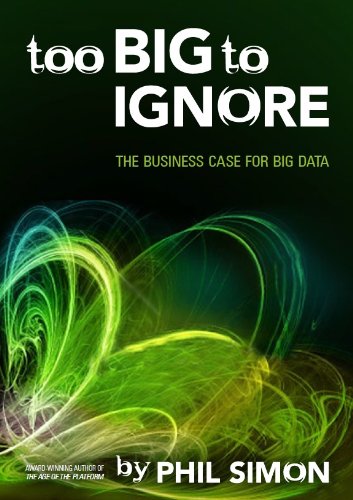

I’ve known Phil Simon since college and he’s one of the only people I’ve known that long that’s taken on a similar writing ambition: he’s written five books, including his latest Too Big Too Ignore: The Business Case for Big Data. The term ‘big data’ is popular, but on the verge of becoming jargon and I couldn’t resist interviewing Simon in the hopes he’d clarify what the hype is about and how his book helps people trying to sort it out for themselves.

I’ve known Phil Simon since college and he’s one of the only people I’ve known that long that’s taken on a similar writing ambition: he’s written five books, including his latest Too Big Too Ignore: The Business Case for Big Data. The term ‘big data’ is popular, but on the verge of becoming jargon and I couldn’t resist interviewing Simon in the hopes he’d clarify what the hype is about and how his book helps people trying to sort it out for themselves.

Q: How is Big Data, which has now become a trendy term, different from the kind of analytics companies have used for decades?

PS: It’s definitely a trendy term. Analytics have been with us for a long time, and they’re still essential. Historically, organizations have used only structured, transactional data to drive analytics. Business Intelligence (BI) and key performance indicators (KPIs) were the rage in the mid-1990s and 2000s. They still matter today. The new boss isn’t totally different than the new boss.

So, what’s different? The types and sources of data behind these metrics. No longer are analytics based solely on structured or transactional data. For example, knowing which customers buy which products remains important. However, there’s a new source driving better metrics: unstructured data brought by Web 2.0, mobility, and the cloud. Now companies can determine what consumers are blogging, tweeting, and writing about on review sites. Amazon, Netflix, and scores of companies use unstructured data to increase sales, innovate faster, and find new insights into consumer behavior.

This unstructured information comprises a great deal of what we are calling Big Data. Analytics still matter, but now organizations have the tools to capture, store, access, and analyze new and critical types of information—and do some pretty amazing things.

Q: This is your fifth book. How did you / are you using big data to help you research and market your work?

I used Google Trends early on to gauge the popularity of Big Data vis-à-vis other terms like Business Intelligence. I wanted to run an A/B test on the title and subtitle of the book but my publisher didn’t like the idea. Eric Reis did that for The Lean Startup.

Rather than download tools and play with them myself, I went old school. I attended conferences, followed people on Twitter, and interviewed real-life practitioners who are actually doing this stuff. In a sense, it was a very different approach than my first book, Why New Systems Fail.

Q: What was the biggest surprise about organizations that have bet on using Big Data?

Big Data has no shortage of myths. The biggest is you have to be a big company to harness the power of Big Data. Not true. Sure, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Twitter, Google, IBM, and other behemoths are utilizing Big Data, but company size doesn’t really matter.

In the book, I write about a number of small companies and government agencies leveraging Big Data. Quantcast and Explorys are anything but big companies, and NASA (even with a $18 billion budget) still acts small by running contests through gamification sites like TopCoder. It’s possible to get a little bit pregnant with Big Data, something that I recommend to organizations not sold on its power.

Q: What is one of the common mistakes you’ve seen people make as they try to adopt your advice?

For one, don’t boil the ocean with Big Data. It’s simply not possible to get all of the information—and you don’t need it anyway. Even Google doesn’t index the entire web. The Deep Web remains largely a mystery It’s a journey, not a marathon. You’re not going to “implement” Big Data in a week. It’s the antithesis of set-it-and-forget-it. It’s an ongoing process, one that requires the willingness to embrace the unknown.

As I’ve seen in my consulting career, strategy eats culture for lunch. Big Data is not an IT initiative. If an organization resists integrating information into its decision-making, it’s unlikely that it will realize benefits from any data—big or small.

Q: How can readers separate the hype from the truth in experts talking about Big Data?

It’s a challenge, but I hope my book will help. I wrote a vendor-agnostic text that covers a panoply of companies. I have no horse in this race.

Although I list some solid rules of thumb in the book, realize that there’s no one “right” way to do Big Data. There are many tools, viewpoints, methodologies, vendors, consultancies, and talking heads with more than a little skin in the game. Every organization wants to be “uniquely positioned” to handle what is a burgeoning area. Take vendor claims with a 50-pound bag of salt.

Finally, understand that many things are still playing out. Big Data tools like Hadoop, NoSQL databases, and the like are relatively new. Yes, there are case studies, but this is evolving at warp speed.

Too Big Too Ignore: The Business Case for Big Data is on sale now. You can grab a free sample of the book here (PDF).