I spoke last year at The World Domination Summit about Saving Your Creative Soul, and had such an excellent time I decided to return. Like last year I’m posting live summaries of every talk (2014 talk summaries here).

What is WDS? The event was founded and led by legendary man of the world Chris Guillebeau and in his opening comments he explained the goal of the entire enterprise (which is now four years old) is to find answers to this question: How do we live a remarkable life in a conventional world? The event tries to answer the questions in different ways and through different activities, but all have three values in play.

- Community – connecting with interesting people

- Adventure – taking risks and doing new things

- Service – making the world a better place

Many of the 2500 attendees are solo entrepreneurs, small business owners, marketers and people with a passion for three goals above. Over 150 people work on putting the WDS event together. Most are volunteers including the core team. And it’s a non commercial gathering – there are no sponsors and nothing is sold other than ideas, and books from speakers.

1. Jon Acuff

He opened with a story about how children have a different perspective, one that can’t always been reconciled with ours. Children can’t understand what Blockbuster video even is. And children today can make mistakes without the world watching. He shaved lines in his eyebrow as a child to look like Vanilla Ice, but no one would remember that now unless he told them. But he remembers how in 3rd grade his teacher posted his poetry on the wall. and he realized for the first time he had a voice.

But he wondered if the the 3rd grade version of himself saw the 36th year old version, what would he ask: “did we become a poet?” And when the 36 year old version told him about what happened, the 3rd grade version would ask “Why did we trade our voice for money?” Which led him to a series of questions and observations:

- Regret has a much longer shelf life than fear.

- Will I face the fear of today or the regret of forever?

- But actually being brave sucks. It feels like you’re going to throw up and you get no sleep.

- Bravery is a choice, not a feeling. You’ll never feel brave enough to do the things you want to do.

- “What’s your daydream?” “To be able to daydream again”

- How do we misplace our voice? We’re too busy.

- If you stay in motion you don’t have to face things that make you emotional.

- Sometimes when you get enough money, you abandon your voice (e.g. bloggers chasing traffic)

- “Can I pay you not to work on things you don’t care about” – yet many “successful” creators end up doing little of the work they set out to do when they started

- Trying to make everyone like you is the quickest way to hate yourself

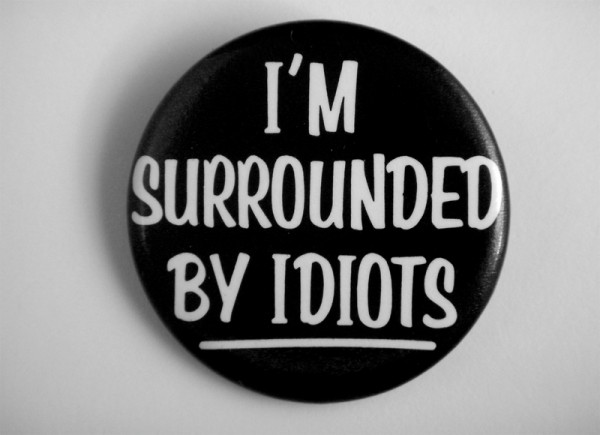

Often people fear not being liked and sacrifice their voice for popularity. Not being able to say no is often a sign you want to be liked too much. He said, “”If you tell someone no and they react in anger, they just confirmed you made the right decision”. We often surround ourselves with people who are good at saying no to us, or who poke at our ambitions, unintentionally, in negative ways. “Are you still trying to start a company / write a book / live your dream?” The word still has surprising judgmental power.

To help him and his fans get back on track and help focus his energy he created dosummer2015 and wrote the book Do Over. Projects he thinks will help you find and develop your voice.

Jon Acuff / @jonacuff

2. Vani Hari (Foodbabe.com)

(Important: This was a difficult talk to watch because of how much she didn’t say about her reputation. Various scientists and medical experts have criticized her not for her health evangelism, but for her specific claims and advice. She made no mention of these experts who have criticized her works on (perhaps) valid grounds, which seemed unfair given her talk portrayed only the most hateful and uninformed kinds of criticism).

4 years ago she had a miserable cubicle job, and was wishing away her time, hoping for the weekend to start. She had no twitter or Facebook account. She was scared to have them or get fired for something she might post. And now there are millions of people on the internet who follow her, and was named one of the most influential people online. She couldn’t imagine then how much would change in just 4 years.

She took on a role as a food activist, having been raised on processed food but wanting to help people to find better ways to be healthy. The surprising popularity of her work surprised her as well as the negative attention she received. She showed a series of slides of hateful Facebook posts, twitter and other social media posts about her, much of it sexist in nature and doxxing. Which is horrible and unjustified for any reason.

The first name for her blog was Eat Healthy and Live Longer blog, which her husband rejected. He came up with foodbabe.com, which she thought was a good name but didn’t match how she felt about herself. She was scared to put her photo on the blog. But slowly she gained an audience. And had success influencing many companies, including Kraft and Subway, to change the ingredients in their products.

On 12/21/2012 at Machu Picchu, far away from her job and world, she got a phone call (or email) that her consulting contract had ended. And instead of being upset she decided to make foodbabe her full time career. Her husband told her “what have you been waiting for?” And that set her on the path to writing a popular book and a successful blog.

She believes that:

- History will resolve itself (meaning, to me, worry about how future generations will judge you)

- “If you don’t like me and still watch everything I do, bitch you are a fan” – Madonna

- “It doesn’t matter how many people don’t get it, it matters how many people do” – (which might be an unattributed Tim Ferris quote from an article on dealing with haters)

I was frustrated by this talk. The abuse women receive online is real and horrible. But a central part of her story is about dealing not with pure haters, but with professional expert peers who disagree with you professionally. I thought she dodged important things central to her story, including lessons she might have learned, and growth she might have experienced, from her tumultuous experience. Instead her message centered on persistence, but not introspection.

Vani Hari / @thefoodbabe

3. Pamela Slim

She spoke at the first WDS and is the author of Escape From Cubicle Nation. She observed that it’s easy as an audience to be inspired, but also to feel jealous of all the success stories they hear. What she wanted to do was to provide tools to take action because “she loves us”. One idea she recommends is a native American tradition called the seven births (or breaths? I couldn’t find a reference to this online):

- The top of your head. The essence of your soul.

- Your breath. Your awareness in every moment of gratitude for life.

- Your language. What you speak and your unique voice.

- Your heart. The center of emotion and what pumps energy through your body.

- Your home. Your physical home and your creative home (or place).

- Your tail. When you sit down on the earth and plug in your tail, you can hear all the prayers of all the animals of the earth. (An idea that appears in the film Avatar).

- Your walk. Daily steps that allow you to leave a garden of flowers behind you.

For any idea, think about it the context of each birth. When you ask someone what they’re working or trying to do, touch on each of the seven from the list and how they relate to each other.

4. Kid President

Robby Novak and Brad Montague are the child / adult team that makes Kid President, a popular YouTube channel. Brad wanted to shape the way kids see the world, and the world sees kids. Brad and his wife started a camp for kids and a non-profit, and the videos they made as a family connected with people who were not in their family. Brad explained “We make videos about things we think kids need to know and we have fun doing it.”

They offered many aphorisms based on their show:

- It’s everybody’s duty to give everyone a reason to dance. (and they had the audience stand up and do “the whip”).

- If you want to be awesome, the secret is to treat people awesome.

- Be cute, be funny, be good. (Robby’s advice to Brad before he walked off stage)

- Treat everybody like it’s their birthday.

- There are many reasons to complain and many reasons to dance. Choose to dance.

Things we learned as kids that could help us be better grown ups:

- Be Nice

- Treat everybody like it’s their birthday

- This is a joyful rebellion. Most rebellions are angry, but not ours. We’re filled with a joyfull vision of how things could be.

- Haters gonna hate, huggers gonna hug.

- Nearly 3 billion people are under 30 today (we have a world of kids)

- You matter

- “You are being uniquely prepared for something magical”

- Sharing is good – not just content, but opportunities.

- They’ve invited fans of their show to send in videos of them dancing, laughing and surprising friends with corn dogs (“Here! I am surprising you with a corn dog because you are my friend.”)

- A fun way for everyone to help homeless people in October. http://soulpancake.com/socktober/

- Take a chance with what you have.

- They made a video of Kid pretending to talk to Beyonce with chicken nuggets. They sent it to her through her website, asking to interview her. She said Yes. The United Nations asked them how they managed to get in touch with her, surprised that Robby and Brad didn’t use an inside connection,

- Ordinary things can become extraordinary when they’re used with love.

When asked by the audience what he wanted to do when he was an adult, Robby answered “When I’m an adult, I want to be a kid. like Brad”.

Kid President / @iamkidpresident

5. Lewis Howes

Lewis Howes hosts the School of Greatness podcast and is a former pro athlete. He grew up into a man thinking of himself as Captain America, a superhero. But years ago he got into a fight, and was surprised by a headbutt from his opponent. It stunned him, and in the emotional state he was in, something unexpected came out. He didn’t know how to take it in his heart, so he responded with strength, and something deep in him came out and beat the other man close to death. After the fight, he stared at himself in the mirror and asked the question: Who Are You? He was ashamed of himself for what he had done.

Universal Myths Men (and perhaps all people) learn:

- You don’t get rewarded for being compassionated

- You get rewarded for breaking your arm and playing anyway

- You don’t get rewarded for saying nice things

- Taking control, winning the game and doing whatever it takes

- This is what most men (and sometimes women) where taught

When he was 8 years old his older brother, his hero, was sent to prison for selling drugs when he was 19. Growing up in middle class Ohio Lewis had never known anyone who went to jail. It was a challenge for him in many ways. He remembers visiting his brother in prison, someone who he had looked up to: it was hard for both of them. And he remembers the day when his brother was released and how the family celebrated. But in the photo of that day, he doesn’t look happy. There was a self image of portraying masculinity he felt he needed to project (Universal Myths).

That night he heard his brother crying. Like a wolf who had lost his pack. But it was really a cry of freedom, and he cried with his family too, sharing relief from the burden of him being away. But Lewis didn’t cry, feeling he had to be the man of the house. (They had an exchange student from Japan who, had only been with them for two weeks, who was baffled by what she observed).

Lewis wanted to go away to school, as his parents often fought. They sent him to boarding school, and soon after they got divorced. But their inability to be emotionally stable affected him.

Months after the fight he still wasn’t himself, and he took a workshop on expressing emotions. And there was an exercise when anyone could share something they’d never shared before. And to his own surprise he felt his heart racing. And he stood up and told a story of being raped by a male babysitter when he was 5. He’d never told anyone before and 25 years of emotion came out of him. But he was terrified of his image and how they would judge him. He remembers crying uncontrollably, feeling he’d ruined his life and would never be loved again. And to his surprise he was embraced by many friends who told him they loved him, and thanking him for sharing and for leading the way (1 in 6 men have been sexually abused, but few ever speak of it).

He asked his brother “Is there anything I could ever do that would make you not love me? “And he said “there’s nothing”. And he told him his story of being abused and his brother was incredibly supportive. And he went to each of his family members and had similar experiences. By not guarding himself, but opening up he created, to his surprise, more connection with people that he thought was possible. He kept sharing it to friends, aware that it was controlling him and owning him, rather than the other way around.

A year ago, after great fear about how it would damage his reputation, he told the story on his podcast. That night, after he hit publish, he went out his window and saw the supermoon, a memory he’ll never forget.

He asked the audience to think about what secret they’re afraid to tell others. What is holding you back? In your family? Your relationship? Yourself? We strive to be the King of Diamonds, but the most successful people become the King of Hearts.

- Will you take off the mask of masculinity?

- Are you ready to join me in becoming superhuman?

Lewis Howes / @lewishowes

5. Megan Divine

[This talk was done so well, so gently and yet so powerfully, it was easily my favorite, and hardest, talk of the day. And to anyone who came to my session on platitudes, I don’t think she used a single one]

Bazu is a child who was 5 years old, and had cancer for 3. The photo Megan showed of him was taken on a rare day when he was allowed outside (rare because his immune system was so weak). She’d known her mother Ellie, seen in the photo, but only online, and Megan had social anxiety about meeting her in person for the first time. She thought at first to just look for Bazu, but then she remembered that Bazu is dead. And had died 6 years ago. Many of the people she knows she only knows because someone has died.

Megan’s partner died a few years ago. She tells a story of her husband, Matt, stopping on a walk by the side of a river to notice whirlpools. They sat down to take a swim and threw the ball for the dog, who ran off, distracting Megan. And from behind her she heard Matt cough, but didn’t turn around. She didn’t turn until he called out her name, and then called out for help. The strong current had carried him out into the water. And he was taken away. She ran in after him, and the dog followed, thinking it was a game. Megan and her dog were carried two miles down the river before being put back to shore. It was 3 hours of rescue divers and search teams until they found Matt’s body a few feet away from where he’d disappeared.

What do you do with someone like me? She asked. Someone like Ellie? We’re all trained to look for happy endings. Our cultural stories are of redemotion and transformation. Things always work out. There is always a happy ending. So what do you do when the possibility for a happy ending explodes into a thousand bits? And pain that never goes away? She didn’t know how to do this. She went looking for stories of people living lost.

She explained that even medically, among doctors, we call grief a disorder. It wasn’t just books and experts that shared this view, but the wider community, and even the therapists. They needed her to be ok because pain like hers is hard to witness. We don’t have stories for how to bear witness. We’re overwhelmed by things that have no easy solution, or no solution at all.

We need new stories. To weave a culture strong enough to not fix was isn’t broken. When you hear the pain in the world it’s not a call to make it go away. It’s a call to love. A call to courage. Pain deserves acknowledgement not repair. The path of bearing witness is the true path of love.

There are things that can’t be fixed and that’s ok. We can love each other in the middle of deep adversity. It’s at the moment when you flinch that’s when you are most called to love. Witnessing is an act of bravery. It’s an act of risk. Hearing someone’s pain and letting them have it is an amazing gift.

Things you can do:

- Notice the impulse to help.

- Pause: what response is called for?

- Don’t fix: Don’t fix anything. Not fixing pain is a radical act.

- Bear witness. Stay present and make space for things to be as bad as they need to be.

It’s been 6 years since her husband died. She explained that we can’t fix her. And no message she can give us exists that would be fair trade for the loss of his life. The redemptive storyline does not apply to her. She offered that WDS asks how to live a remarkable life in a conventional world, and one way to do that is to practice love in a world where terrible things can happen, to love fiercely and intelligently in a world where children die and loved ones can be swept away. She believes we can.

Megan Divine / @refugeingrief

[I couldn’t stay for Day 2, so the above notes are from Day 1 only]