The hotel where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on April 4th 1968, is now the primary site of the National Civil Rights Museum, and it is a powerful place. The sign to the hotel and its exterior is preserved for history, the interior thoughtfully converted into a modern museum space. I visited for the first time recently during a road trip through the South of the U.S.

Before the trip I knew the basics of the civil rights movement in America, but was surprised at how much I didn’t know. I’ve had this experience about history before, but it never prevents me from having it again. We always think the major events are enough to help us understand something, but then you dig in and discover how much went on before those major events.

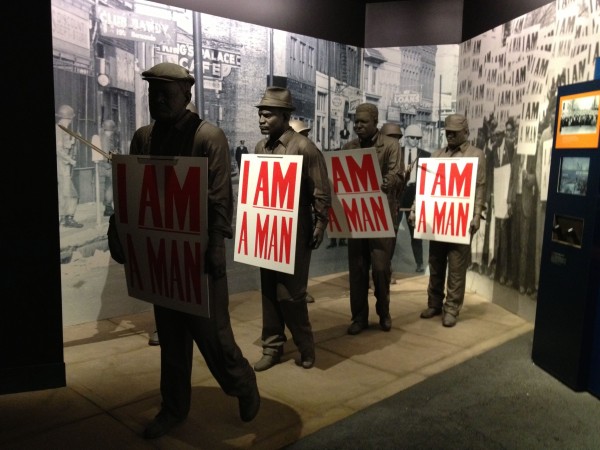

A stop at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute two days before broadened my knowledge. There were many more people who made sacrifices and took personal risks than I realized (Fred Shuttleworth’s story was particularly powerful), and the struggle lasted far longer. The effort not only to raise awareness, but to find support was slow, painful, and plagued by brutal setbacks.

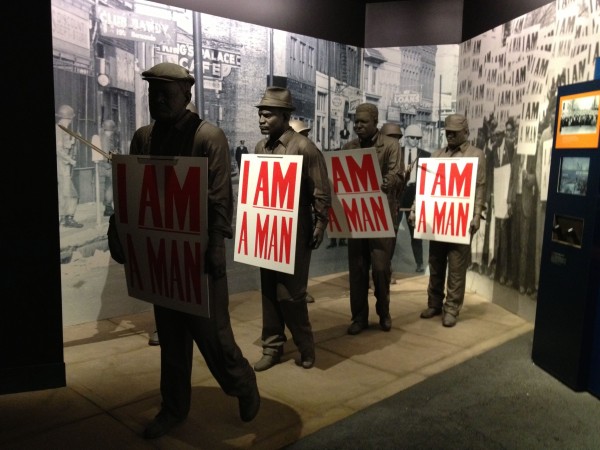

I expected, given its location, that the National Civil Rights museum would center on the story of Martin Luther King, Jr. But it was clear in the first few minutes that there were several decades of important developments that led up to the rise of MLK visibility.

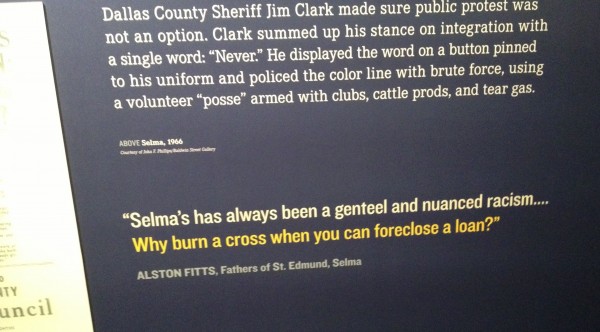

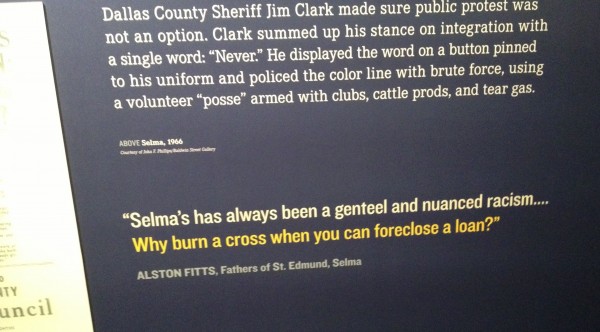

The many dimensions of racism and how proud some town leaders were of their outward defiance of any semblance of civility was disturbing. “Why burn a cross when you can foreclose a loan?” expresses such clear intelligence about what they were doing (economic intimidation). Even if you didn’t agree with these attitudes they were flaunted publicly and pervasively. Who could be brave enough to stand up against this kind of open harassment?

Segregated schools, given their own section in the museum, made clear how racism wasn’t just about the current generation, but also was applied to children, and therefore, the future. How do you divide children? I stood in that room and wondered how lost a people could be to so clearly take opportunities away from future generations. My 21st century eyes struggled to see this in a way that didn’t make me sad for humanity, as much as I didn’t want to see it that way. How do we do this to each other? How have we done this to each other for centuries? It’s impossible not to walk through the museum without feeling mystified about the human species. I’ve felt similar thoughts in Holocaust museums and at WWII sites (See What I Learned in Hiroshima). There is a brutality in our history and in us that we haven’t evolved past, if we ever will.

As I walked through the museum the big question I asked was: what would I do? In every story of awful behavior, vicious cruelty, and repression of ideas, I tried to imagine how I’d respond if I were a victim. What action would I take? Would I have done a sit-in at Woolworth’s? Would I have protested peacefully? Would I have gone on a Freedom ride? How civil would I be? Would I have been violent? Where? How? How brave would I be, and what would that word even mean? Or would I hide and ignore the whole thing?

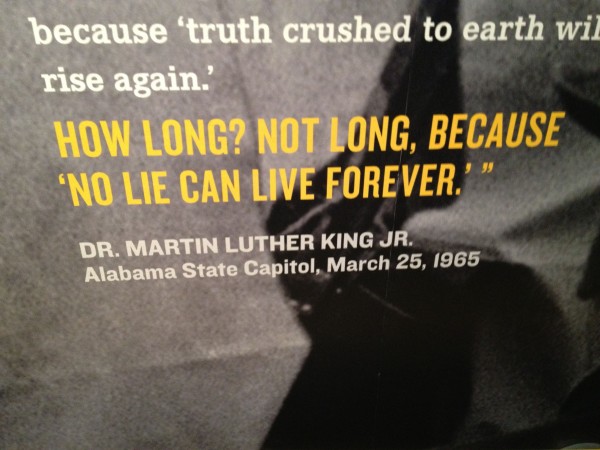

And with each step I took from room to room I felt waves of respect for how many people were willing to make sacrifices to make arguments for rights that should have already been theirs (“”I’m tired of marching for something that should have been mine at birth” -MLK). I really don’t know what I would do. I can’t know. But I can try, today, to do something for the causes I believe in and injustices I see.

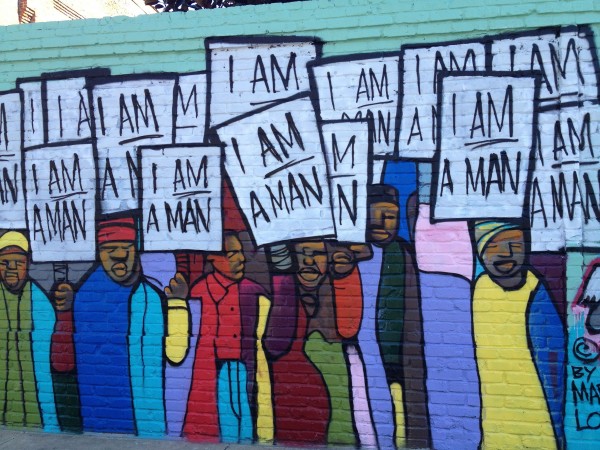

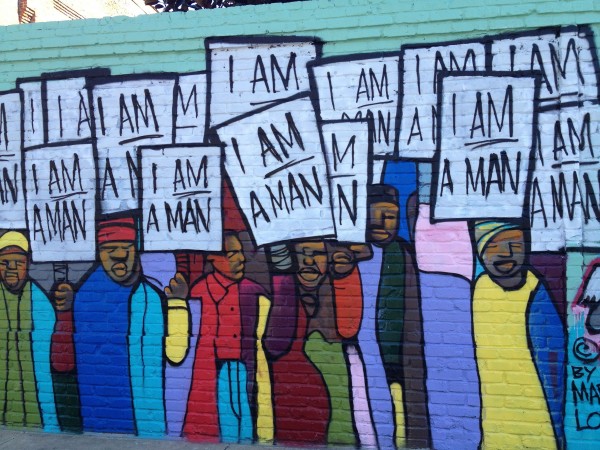

Out in the streets of Memphis are a series of murals, and had I not gone to the museum I wouldn’t have completely understood what they were about, and how they fit into the larger story.

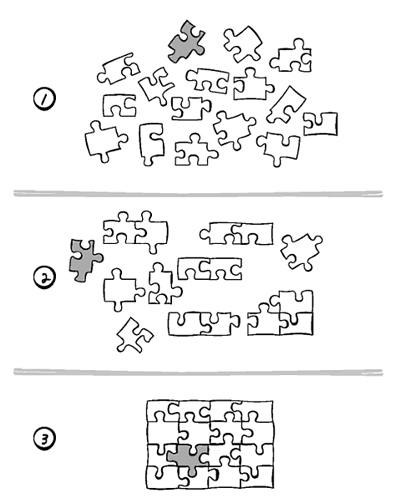

The famous stories like Rosa Parks, a story I’d learned as a child, always seemed like a singular event in my memory. As did MLK’s I have a dream speech. But it was only during the second half of the experience at the museum before either one was mentioned.

It took years of work and sacrifice before Parks’ protest for there to be enough of a story for hers to get broad attention and have the wider effect it had. The story of Fred Shuttlesworth, a name I first learned in Birmingham, came up many times in the museum, and I was inspired again by his intelligence and courage.

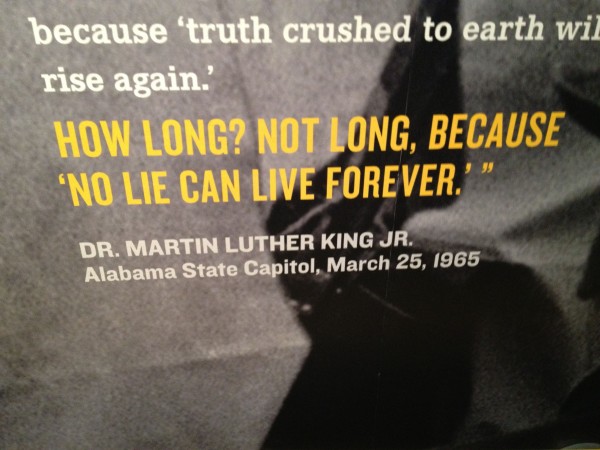

Its only towards the end of the story that MLK comes into central focus. In the movement he was a major wave, not the ocean itself, and as obvious as this sounds now, until I’d walked through the museum I’d never had that perspective before, or had it so clear in my mind. The role of the FBI and other government organizations in harassing black leaders was sad too, another reminder of what the status quo was like in the 1960s and how if we believe in progress, there is always something worth improving in any status quo.

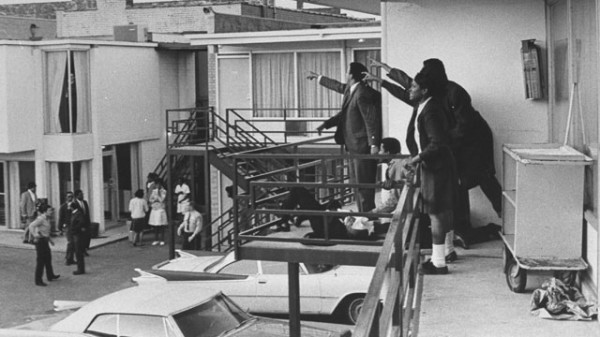

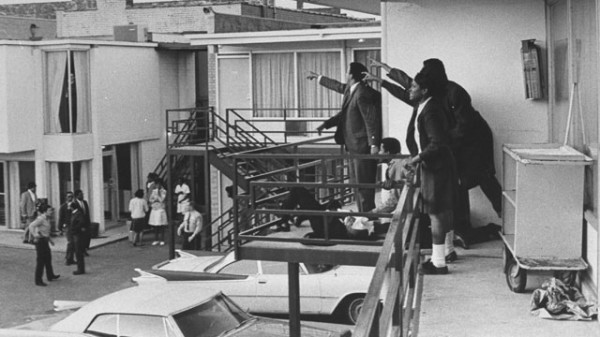

From outside on the street there’s a plaque just beneath room 306. I watched many people stop to take a photo of this most famous and tragic place, and then walk on. Like me, before I went inside, I knew this was a horrible and important moment in history, but I didn’t fully understand. I felt sad for the people who moved on without going into the museum. They were in a historic place, but didn’t understand the history that led to that day.

Standing in the room itself you can’t help but look across the street to where the rifle was fired that killed MLK. It seems so close and so quaint, and it was. There was an ordinary, neighborly grace of civility violated here. It’s an ordinary street, with ordinary buildings, made extraordinary for horrible reasons.

The museum continues across the street, and you can look the opposite way towards the hotel, out the apartment window where the shots that killed MLK were fired. It was not a hard shot to make. The cruelty of it is made worse but how peaceful this place is now and must have been then.

There is a marker in the street that quietly expresses where the shot traveled. It’s a silent, dark memorial, that some visitors might not notice.

Standing in the window was a morbid and disturbing place to stand. I felt obligated to look and to stop for a moment. I thought about what the world would be like if there was never a reason for a museum like this to exist at all, much less in this specific place. I’m still mystified by how anyone can want to hurt someone who is a leader of a non-violent movement. It’s only cowards, filled with hate they don’t understand, that can act this way.

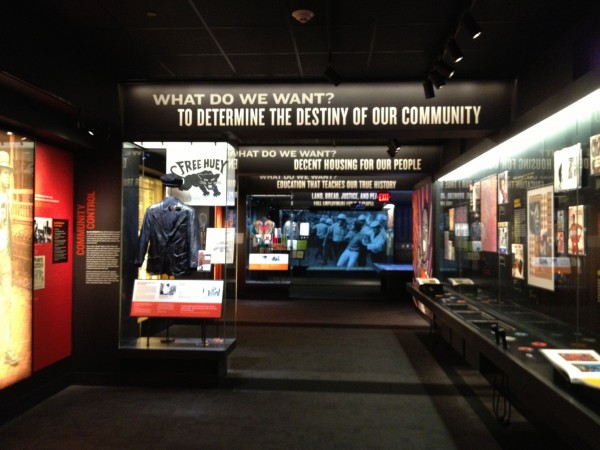

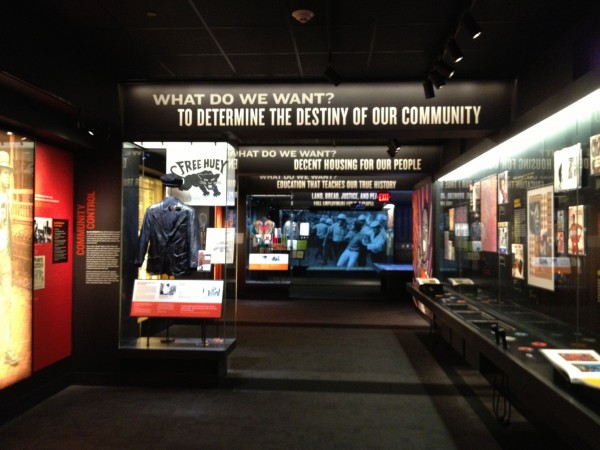

The museum ends with questions and the idea of community. I like that word. I like the idea of people creating a shared place together where everyone has an approximation of equal opportunity, and everyone contributes to doing what they can to help their neighbors, in the broadest sense of the word.

I strongly recommend visiting the museum. It will put everything going on today in America in a wider, deeper context, which can only help you sort out your feelings and what you want to do or not do about them. There’s so much history we, collectively, have yet to learn from.

- What would you have done then?

- What will you do about injustice now?

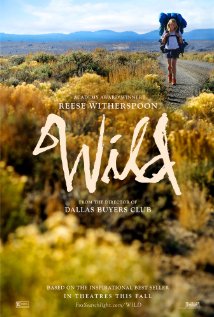

Many books are made into movies, but most movies aren’t very good. Movies are hard to make, period. Even with a great book (

Many books are made into movies, but most movies aren’t very good. Movies are hard to make, period. Even with a great book (