I gave the opening talk at the first Leading Design event in London, hosted by Clearleft. I spoke about the challenges of being a designer in the real world, and you can grab the slides here: Design vs. The World (PDF). I stayed for both days of the event and took notes (liveblogging) for every session I went to (using a version of the Min/Max note technique).

You can also find:

Farrah Bostic, CX is the CEO’s Job

She romped through the history of business schools in the U.S. and noted that it was Selfridge who coined the irritating term “the customer is always right” (1909). She critiqued Taylorism (1911), and the management centric philosophy he had “Managers are inherently smarter than workers”. She also disputed the Ford quote about “if I asked people what they wanted. He didn’t invent the assembly line but did employee it successfully at scale.

Ford did actually say “If there is any one secret to success it lies in the ability to get the other person’s point of view and see things from that person’s angle as well as your own.”

She emphasized how Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction is central to startup culture today:” we must harness change otherwise it will drown you”

Next she referenced Drucker who posed in 1954: “The purpose of a business is to create a customer, the business enterprise has two – basic functions: marketing and innovation.. all the rest are costs.”

Today it’s common for people to confuse principles with processes – for example you don’t “do lean” you “think Lean”.

Another customer value model is the Toyota production principles:

- precisely specify value

- identify the value stream for each product

- make value flow without interruption

- let customer pull value from producer

- and pursue perfection

A disturbing (or exciting) fact is that Fortune 500 companies last shorter than ever. And yet CEOs get paid more than ever (and tenure is shorter, 6 years on average). Worker income stays the same.

Many famed books that claim theories to explain why some businesses last don’t hold up over time. She suggested we “Read books and then wait 5 years and see how well the theories hold up” – Good To Great is a good book, but many of the highlighted companies have not lasted.

A common mistake CEOs make is to spend more time talking to their best customers rather than their next customers. The American TV show Undercover boss is predicated on an essential truth: often the CEO has no idea what is going on in the company.

“FOMO leads to dalliances not marriages”

“Malcolm Gladwell effect: CEOs go to a party and hear about a book and get FOMO so they fall for the latest trends and are prone to hiring consultants who sell the latest trends and buzzwords (offered my Eric Reis)

“The data will tell us what to do” is a myth –as if a magic voice can speak to you off camera with the secret truth.

Recommendations:

- Uncover your riskiest assumption

- Get to know your next customer

- Commit to change (air cover and ground cover)

- Make ruthless sacrifices (jettison old business and people who don’t fit the new vision)

Gail Swanson, How to present to decision makers

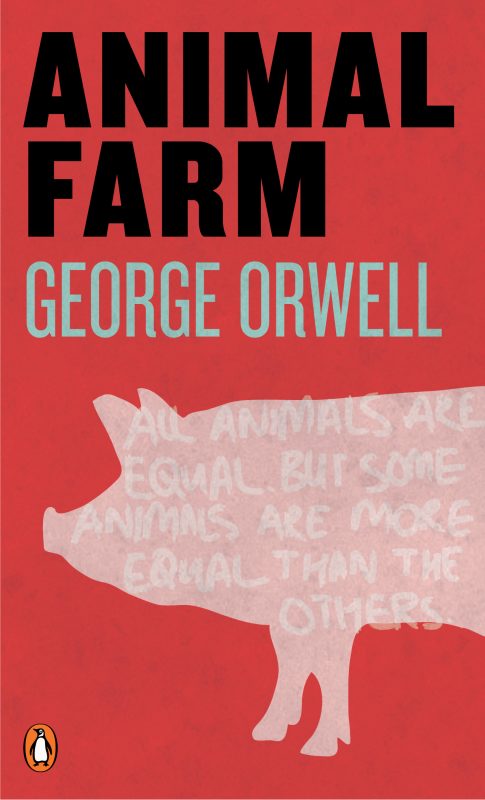

“Some ideas are so stupid that only intellectuals believe them” – George Orwell

We tend to believe “If we have the best rationale for why we made a design decision that will make it easy for decision makers” – but this doesn’t work very well

Design is change – FUD fear uncertainty and doubt. Designers enjoy it, it is our business but we have trouble empathizing with people who don’t.

Human Centered Change is a good way to think of what we do and Behavioral science can help us. But one presentation is never enough to create influence– it’s a series of points of communication in sequence that creates influence

Your Role

- Rebel – I made something and the world should change

- Organizer

- Helper – facilitate discussion

- Advocate – create a belief and partnership

When most designers show their work in presentations they are asking “Is this good” – this is non productive. You are asking someone to check your homework and give you a grade. It’s best to skip this and focus instead on “Is it right for you? For this situation/scenario?”. You are a professional and should stand behind your work.

How to you build an effective presentation:

- Who is in the room?

- What is their POV?

- What background do they come from?

- Are the business focused? Service? In-house?

- What are their pressures?

- What forces are acting upon them?

- How are they rewarded?

A good framing question is to think about: We can get A to do B if they believe __________________ .

A narrative endows information with meaning. Giving data points doesn’t help decision making – it leaves interpretation to them. Part of our job is to provide the story and framework for interpreting data.

Lead a conversation about risk. “What is the risk if we are wrong?” – often it’s something that can be anticipated and made less scary.

The work to create the design is as valuable as the design itself. It helps to answer questions, test and validate assumptions.

Tactical language (vebal judo book)

- Build common ground

- Strip phrases: “I appreciate that… but” “I understand that concern but we can address it if we…”

- Paraphrase – people rarely say what they mean. Ask clarifying questions.

What is the experience of you? Are you protecting yourself by being an expert? Are you pompous? Or are you connecting with them and do they see you as an ally?

Sarah B. Nelson, A Place of Our Own: Making Networks Where Design Thrives

“Why is it that some projects succeed and some fail, even when it’s the same group of people” – question she’s obsessed about . She learned a great deal by trial and error and making mistakes, as we all usually do.

IBM where she works is huge. But it’s easier to scale down than to scale up, and her lessons should be easy to apply. IBM 350k employees. Founded in 1905. Definitely Big and Old. She works on thinking about what makes great creative environments.

She asked people in design studios why they were great places to work and these were some of their answers:

- You can work alone or together

- Ideas and knowledge are shared

- My imagination is nurtured

- Everyone is pushing each other to be best selves

- I can draw on the walls

- People can collaborate regardless of their role

She asked the audience about the size of the teams and explained there are very different challenges at different sizes.

- Team of 5 (Magic Number)

- small team

- information flows freely

- you know what each other does and is working on

- Team of 11 (size of family unit – enough people to spread work, but few enough to have deep relationships) subgroups

- light processes

- someone dedicated to process

- still visible knowledge

- Team of 20

- Team of 35

- systems starts to break down

- suddenly everyone can’t be involved in all decisions

- Team of 70

- people who like small environments slip away

- system breakdown

- Team of 150

- Dunbar number

- GoreTex organizes company in business units of 150 people – buildings and parking lots only hold 150 people. When the parking lot gets full, they build another building. Merit based flat system.

The basic needs of creative environments are the same regardless of the size.

What to do?

- Establish standards and tools

- Provide paths, shortcuts and guides

- Empower designers and leaders

Enabling conditions

- Social environment – strong relationships, sense of belonging, diversity, empowered ownership, dependability

- Physical environment – Flexibility, support visual thinking, enabling technology, abundant materials

- Emotional environment – Stability and Safety, growth mindset, how safe is it to fail in public, is critique useful or ego driven, respect (attrition is caused here)

- Intellectual environment – stretch goals, new ideas invited, cross-pollination, knowledge sharing

People + Practices + Places = Outcomes (ibm.com/design)

What can you do?

- Establish standards and tools

- Provide paths, shortcuts and guides

- Empower designers and leaders

Andrea Mignolo, New on the Job: Your First 90 Days in a Design Leadership Role (slides)

As a design leader you are responsible for being a design ambasaor and to build design into the DNA of the company. She examined different leaders from Game of Thrones and asked the audience if we thought they were good or bad managers (Jon Snow / Jofree).

Authentic leadership – built on ethical foundations. Takes a lifetime of practice (principles aren’t necessarily easy to practice)

For four years she lead a 40 person guild in World of Warcraft. The other leaders had different styles and they wondered if love or fear were been ways to lead. And they experimented to see which work best – they found they call all work if the match your style.

Good design & good leadership share many traits. They are both: thoughtful , serve people, appropriate, empathy, intentional, vision, collaborate

“Designers can not design a solution to a disagreement” – Montiero

Harley Earl was a designer at GM –”My primary purpose for twenty eight year has been to length and lower…” His north star, or guiding idea, was to make GM cars more natural and oblong in shape.

What is your vision for design, what do you believe, what is your north star?

- What is your company’s north star?

- What different is it from yours?

- How can you minimize the delta?

- What did you learn in your interview?

When starting a new thing 30/60/90 days are arbitrary units of time for thinking about transitions to new things. Instead she offered a more useful one: 10/10/40/30.

The First 10/10/40/30 – Is the pregame. You are trying to gain clarity and information. Take your north star and apply it.

But apply it to the context of the “layer cake” of your world:

- Board of directors

- executive team

- company

- design team

- colleagues

- departments

- public

- parent

During pregame, connect early and socially with as many people as you can. Do sleuthing about your predecessors and what history there is that defines perception of your role

10/10/40/30 – Critical 10

Rigorous planning is the best prep for improvisation, Expect the plan not to work as planned, but to have developed it will help you deal will all of the situations you couldn’t have possibly planned for.

Think about how you want to be perceived and invest in it. She chose Optimisit, Open, Awesomely competent. Think about your origin story, which you will be asked about often. It helps shape how you are percieved. Good origin stories: why you do what you do, other organizations you worked in, and why you are excited for your new role.

Boatload of meetings. Take notes and have beginners mind. Write down jargon and abbreviations (and ask for clarification later). Look for allies – people who care about design. They may not use design language but there are giveaways. Dev who spends extra hour on details. Marketing who emphasized brand.

Talk to people in different departments to ask: how they see design, how design can help them.

10/10/40/30 – Making Moves

Formula for Trust: (Credibility + reliability + intimacy) / self-orientation

Earl’s design studio at GM. When he joined the company his department was called the beauty parlor and his team the pretty boys. As their reputation improved people wanted to visit the studio – it was a cool place to be. It made design visible (externalized) and helped establish credibility.

- Foundations

- Pre game

- Critical 10

- Making moves

- To infinity and beyond

As a leader, it’s Education, inspiration and facilitation core skills.

- Buy in

- Credibility

- Trust

- Communication

- Ah-ha moments (and ha ha moments)

Julia Whitney, Culture, culture, culture: tales from BBC UX&D

She shared a story of Rupert, an engineer, discovered a problem with a mixing board used for live production in the BBC. It was a difficult scramble but he dropped everything else to fix the problem and solved it before any listener noticed.

Later, In an offhand meeting, she mentioned an idea for consolidating how their clunky wifi worked. A few weeks later a set of wireframes came back with an overdesigned and misunderstood set of requirements. This reflected something about BBC engineering culture – they had the habit of dropping everything, respond to a crisis, and fix the problem quickly, but without clarifying or communicating well.

“[Culture is a] shared set of unconscious assumptions as it solves their problems ” – Edgar Shein

One way to better understand a culture is to ask: what counts as heroic behavior in this culture? That’s what helps explain Rupert’s behavior.

What levers does a leader have to influence culture? She offered two kinds.

- Structural methods

- Embedding mechanism (leadership behaviors)

BBC (where she used to work) is structured in genre silos (news, sports, etc.) UX was organized in the same way. Design became increasingly divorced from development. Churn escalated. When she took over the leadership of the group, she admits she brought her own cultural assumptions. Eventually they arrived at a functioning model called federated ? )

In 5 Dysfunctions of a Team, it’s explained that there are five layers that contributed to teams that function well:

- Trust – I can give my true opinion with repercussions

- Conflict –

- Commitment –

- Accountability –

- Results –

Regarding conflict – she realized we were being way too nice to each other and were unwilling to disagree. This kept information off the table and kept commitment from being heartfelt. Our decisions were too wishy-washy. “Fuckmuttering: is the complaining you do outside of a meeting to vent your true feelings”

The invented the term Productive Ideological Conflict – useful conflict that is explored until a resolution is reached.

Conflict mining: agreeing to dig in to conflicts rather than avoid them.

Motto “We will not prioritize relief over resolution”

Shein also suggested that unless leaders can acknowledge their own vulnerabilities transformational learning can not take place.

Q: “What changes in your behavior does the culture you are trying to build require from you?”

Nathan Shedroff, Using the Waveline: Mapping Premium Value to the User Journey (a new tool for planning deeper customer experiences) (Slides)

There is a long history of tension between business and design, some of it is historic and some is self-inflicted.

As an example, Minimum Viable Product vs. Experience Prototype, represent two different world views and preferences. Business prefers optimization Designers prefer exploration.

Five kinds of value:

- Financial (Business, Quantitative)

- Functional (Business,Quantitative)

- Emotional (Design, Qualitative)

- Identity (Design, Qualitative)

- Meaningful (Design Qualitative)

Value is always between transferred between two people: customer/company, supplier/vendor, etc. In order to exchange value you need to have two people in a relationship. Everyone, including businessmen, agree relationships matter but it is not accounted for in their models and theories. Therefore we are all in the relationship business. But we don’t have any relationship tools.

Qualitative value is most powerful (can override rational thinking in decision making, like buying cars), but harder to measure and mostly invisible in strategy and tatics. Market research is worse than worthless because many decision drivers are overlooked (qualitative).

The waveline was a representation of music created by Ernst Toch, who wrote The Shaping Forces of Music. It expresses the intensity of music as a series of curved lines, like a chart.

There are three elements Emotions, core meanings, and triggers. And combined define the intensity and value of experience over time.

The hero’s journey of Joseph Campbell can be expressed as a kind of waveline. It’s a pattern of emotion, meaning and triggers than has been established over time to reliably create satisfying experiences.

Leadership: the ability to clearly communicate a vision of the future others want to follow

Numbers are a great supporting act for a story, but it’s not the narrative.

See slides for examples (it was a highly crafted visual presentation)

Rochelle King, The itchy discomfort of trying to fit in

Japanese culture has a strong sense of aesthetics. It’s not just the appearance of the final product but the process it took to get there.

Wabi-sabi: imperfections can provide a kind of beauty. Growing into a leader is not easy, and we all feel burned and scarred along the way. It’s sometimes a result of the environments we’ve been in, and sometimes it’s self inflicted, but either way our experiences, good and bad, shape us into who we are.

Growing up as a Japanese American she learned Japanese traditions, but later in life learned she needed to adopt new ones. Japanese culture divides people into and in group and out group. The out group supports the in group. You can get so caught up in supporting others as a manager that you defeat your own goal and make it harder for the team to functional well, by sacrificing too much.

The nail that stands up gets hammered down – Japanese proverb

There are parallels between being a minority and being a designer in the tech world:

- How often have you felt like the only person of your kind in a room?

- How often have you felt that your background made you different than those you work with?

I’ve rarely seen people sustain at being successful when they try too hard to be something they are not. But this doesn’t mean to not evolve – you need to start by knowing yourself and then evolving from that source.

She admitted she relapses all the time. A definition of internet fame is how many followers do you have? How many articles are written about you? She admits that she posts sometimes, but not consistently and she’s not good at it. But things like building a team or solving a problem are natural and matter more.

Part of being a leader is being able to act as a bridge to the rest of the company (or to translate).

Tower builders vs. mountain builders. Towers are taller and easier to notice, but mountains are more stable and harder to move. (attributed to John Maeda)

Leadership isn’t always tied to your discipline, it can be your skills as a human and they can be applied anywhere or to anyone.

She shared stories about her recent experience at Spotify, in contrast to her experience at Netflix. Consensus driven culture can be great: when she asked for design to be included they said great. But it’s frustrating when a decision is best made by design (or any role) it’s hard to get the power to make it.

The language of the company was Guilds, tribes and squads, was initially rejected by her, and she thinks had she adopted it sooner it would have helped. But you can only assimilate for so long before you need to find a way to stand out. Design is a different perspective than marketing or tech roles. Fitting in will only get you, and the company, so far. Knowing when to pull the trigger is tricky – she’s never been early enough. There’s no formula but knowing this point will come and being proactive is helpful.

James Higa was sent by Apple to build their office in Japan. He had a hard time recruiting. The expectation is when you take a career in a company you will stay there for your life. Many were skeptical of joining a US company with a piece of fruit as its logo. He had to meet with some of their parents to convince them. He was more successful recruiting women than men – they had less career pressure. Sometimes being an outsider provides strength as you are free from the pressures that insiders have.

Leadership is not an end-state, but a journey.

Mike Davidson, Former VP of Design at Twitter

[Andy Hunt interviewed Mike for the entire session].

Mike worked as VP of Design at Twitter from 2012 to 2016.

He explained how once you get to a certain level the design teams often need to break apart and be distributed across the company. But you can balance the tradeoff of being embedded vs. centralized if you’re smart. At Twitter they kept a central design office that they used for larger meetings and critiques so there was a familiar home base, but most designers spent the balance of their times with their teams.

The team was 15 peopple when he was hired and grew to 100 before he left. People are surprised the design team was so large, but there’s more than one just one twitter. Each platform, each phone device, plus tweetdeck, fabric (?), the advertising UI – many more pieces than people think.

The subject of diversity and inclusion was new for him at Twitter – the team was 80% male when he started, but when he got to 100 people it was nearly 50/50. They did it not by data, but by listening to the stories of the female members of the team of what their experience is like. Some of it was about twitter, some about tech and some about the world.

One story Mike shared was a woman who explained she’d often go for weeks and never see another woman in a meeting. “Most of the meetings I’m in it’s me, 10 engineers and a PM”, all male dominated roles. She explained that all it takes is one other woman in the room for me to feel much more comfortable, and to be able to look at each other and know “that is only something a dumb white man would say”. That story had more influence on understanding on what was wrong, and what the goal was than any of the data they had.

The people who deserve credit are the women who told these stories, did the research. All Mike claims credit for is providing the space for this kind of discussion to start, and using his position to make different kinds of hiring decisions in the future.

He offered that diversity is the right thing to do socially, but there is a business case for it too. One of the biggest challenges is getting a view of your potential audience and if you’re just a bunch of white men in a room in San Francisco you’re not going to get it right.

He talked about one design problem where diversity helped find a solution. Permission gates: this is when an app wants get location information from a user’s phone. The stupid thing is to use the system iOS because you can only do it once. But a permission gate is your own UI, which you can put up as many times as you like, and if approved you go through.

One design idea they had was a tent as the icon for the permission dialog. But an Indian woman explained that this icon would make no sense in India. They could have discovered this through research later, but they got that insight fast and for free.

Young designers start off very cocky and think they can design anything for anyone and don’t need any data. It’s ok if you have young green people provided you manage them to do the research and use it to debunk the hubris that you see in confident young designers. You don’t use research slide decks, you use video showing people struggling with their design and it will quickly disavow them of their assumptions.

He thought of his team as a family and this helped with retention. “We don’t hire assholes, we don’t hire delicate geniuses.” He wanted his team to be a rock, a reliable culture, even if the larger company was having trouble. They’d organize out of work social events – being an executive is a bit like being a cruise ship director at times, and that means you have to organize parties and events.

When asked about what he might do next, he said “I find that unplugging is therapeutic and healthy. The experiences I want to design help people pull away and be in the real world”

Jeffrey Veen, Crafting a Creative Culture

We can train ourselves as leaders and teams which set of responses we will have to events.

Equanimity – state of emotional stability especially in difficult situations. Grace under pressure.

Story: Jeff was the CEO of Typekit, a font service for CSS, that is host based. He woke up one morning before his alarm, and discovered a lot of activity on the company slack channel. He looked at the server stats and discovered something was very wrong. Something was broken with how fonts were being deployed.

They had known a major announcement was coming on Dec 19th that would spike their traffic. They had 3 days to plan how to handle it. They tried to manage it like a rocket launch. They decided to remove all of the secondary issues, partnerships and business issues, and let engineers focus purely on the launch.

They broke down the problem into small pieces and discovered that the server that redistributes their fonts was problematic, and decided they could make their own. They once had this in the project plan to do it over 8 weeks, but it had never been done – so they decided to do it on Dec 18th. Plan was to make it in a simple efficient way, and they succeed and launched it that day.

“On Wednesday we decided there was no possible way to get this project done before the end of January. We launched it this afternoon.” – @ph

Three lessons:

- Everything breaks – every thing is connected to the rest of the world. A storm can hit another part of the world and damage a system that you didn’t realize you depended on.

- Everything contributes to the user experience

- Teams can thrive with equanimity

Google’s Project Aristotle – tried to answer: what makes a good team? The analytical approach they took initially revealed no insights. But with a psychological approach they

A key criteria was that people had “a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up”

“Some people believe tension is a good creative tool. I’m not one of those people. I’m not trying to control them, I’m looking to amplify whatever it is about them I find compel. I keep the environment relaxed but focused.” – Steven Soderberg

Jeff saw part of his role was to build a sense of great taste on his team and across the company:

- More exposure to great work = better design vocabulary

- A diverse team leads to better product insights

Three Meetings

- Product Review (not Design review)

- Anyone could come

- Not a forum for expressing opinions

- Working sessions for group problem solving that is divergent or convergent

- Bad: I don’t like blue Better: Why is that blue? Great: Is color important here?

- Postmortem

- First response when things go wrong is to find the vilian and punish them (Fundamental Attribution Error)

- Sakichi Toyoda – The Five Whys. It’s a way of letting all employees know they are safe to do their work.

- Group Chat

- Act distributed even if you are not

- Communication compression – chat models encourage brevity and reduces hierarchy effects

- Ambient accountability – things that people do can be passively visibly and celebrated with micro-appreciations (e.g. animated gifs, etc.)

He closed with the suggestion we find work that excites us and people we trust and to go make great things.

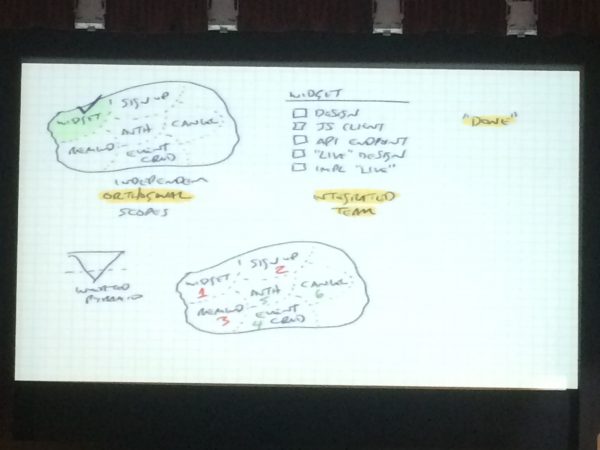

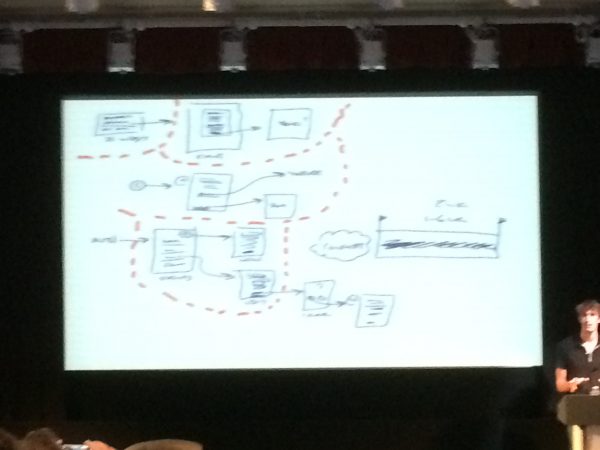

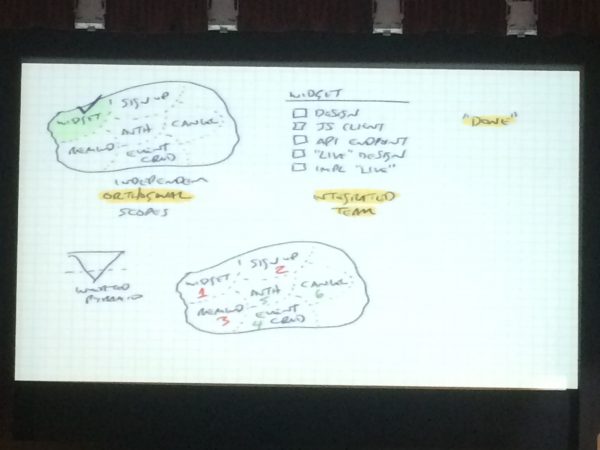

Ryan Singer, Basecamp

When you get power, will you inherit the same BS patterns that frustrated you? He offered a simple, straightforward way to manage design and development work, based on what Basecamp does.

A typical project in most organizations:

- Kickoff

- Intermediate deadlines (sprints, etc.)

- Big Deadline

Their approach

Example: static site with livestreaming of how basecamp works. Imagining a dynamic element that advertises these events, but build it without a CMS. And need a way to send reminders to people for when these events will happen.

Two phases

- Concept

- Shipping mode – begin date and end date. No intermediate milestones. Longest is six weeks.

He offered the metaphor of butchering an animal.

Animals have an inherent anatomy. You can separate parts naturally. The goal during shipping mode is to look at the concepts for the inherent anatomy of the design. A project anatomy. Each piece has orthogonal scope – they can be thought of and worked on independently.

For each piece or widget they then inventory all of the parts they need to build.

They think of it as an inverted pyramid model – the most important work is done first. They order the pieces and work on them in priority order. They mark items they can launch/ship without (with a ~).

They can then work by managing scope. If things take longer they simply don’t do as many of them. When the time box runs out, they reach the once mythical state they call “Done”.

Duncan Lamb, Let’s make something good

He called out on how events like this tend to say the same things – like a Bernie Sanders rally with better fashion sense.

LEAN biases towards cheap and fast at the expense of good. If people are not emotionally engaged in your product or service they are not enganged

(From Paul Dolin Designing Happiness) Two spectrums – Pointlessness-Purpose / Pleasure-Pain

The ease of measurement bias:

- We lean towards the things we can more easily measure. Emotion, joy and 1happiness are very hard to measure.

- We confuse the word viable with the word feasible. When we make MVPs we’re often making MFP.

- We bias towards quantity not quality – we are fickle creatures and we like new toys. Before you know it our code base, brand and product are a mess.. Like MacGyver, we are pragmatic people. If it works, then it’s good. When you found a company you hire engineers because they can build things – designers just talk about building things (joke).

What is good? How good is good enough? Trio: Does the job, built right and aesthetics (he offered the way a car door feels when you close it, and how it influences purchasing choices, an example of the potency for aesthetics)

How do you create a culture where people care? Designers get this intuitively but the challenge is to get everyone else to see it that way. Three approaches:

- Despotic founder runs around yelling and screaming and firing people

- When you are competing against a better design

- People genuinely care and take pride in design

Braden Kowitz, Fostering Design Culture

We are influenced by the behavior of others around us (elevator video).

Three patterns he has seen work:

- Faith in Quality – data is useful, but there is always unmeasurable value. The dark matter of value. We are sure it exists but we can’t see how it interacts with what we can measure. Designers need to be advocates for the unmeasurable and one way to do this is through critique.

- Hold Design Accountable – Designs often get distracted by design – we see well ‘designed’ products that fail (which should mean that the design was flawed). Designers contribute Surface value, User Value and Business Value. Commanders Intent – Battlefields are chaos. As a leader we have to do more than give orders, but express the goal the order is intended to satisfy.

- Design is Everyone’s Job – Software quality used to be a role, but isolating it sent the wrong message to rest of organization. Now engineers write unit tests, a software quality technique. Exposure to customers is one way to help make design everyone’s job (over 30mins per week per employee). Designers have to accept that good ideas can come from anywhere.

Jason Mesut, Building your A Team

- Frame – scope and position the team and roles

- Hire – attract asses fit of people

- Fire

- Grow – develop individuals, scale team. Increase presence

- Adapt – to changing needs and the team dynamics

- Exit get out to let others grow and shape things

How you manage these changes often. You have to reframe often. Framing and Hiring might be the most important and have the biggest impact.

Framing: understanding the position your is and where it needs to be.

WATCH:

- Work

- Approach

- Teach

- Career

- Help

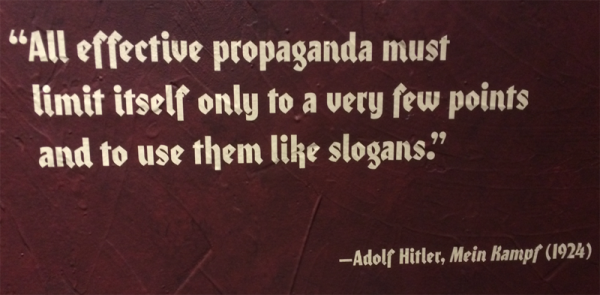

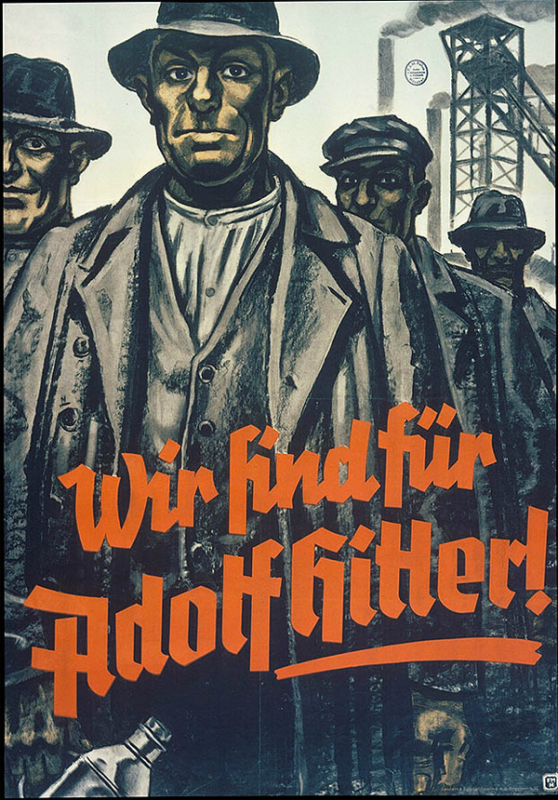

The Nazis’ platform did not initially scare many voters. While many voters weren’t necessarily at first attracted primarily to racist themes, they were willing to overlook them in hopes of economic promises. The Nazi’s carefully crafted different messages to different audiences, using nuance to signal to their deepest supporters without offending more moderate voters. This poster at right (“We’re for Adolf Hitler”) was aimed at unemployed coal miners, suggesting a vote for Hitler would bring their jobs back. At the same time

The Nazis’ platform did not initially scare many voters. While many voters weren’t necessarily at first attracted primarily to racist themes, they were willing to overlook them in hopes of economic promises. The Nazi’s carefully crafted different messages to different audiences, using nuance to signal to their deepest supporters without offending more moderate voters. This poster at right (“We’re for Adolf Hitler”) was aimed at unemployed coal miners, suggesting a vote for Hitler would bring their jobs back. At the same time